To Feed, to Nurture, to Protect

Remembering his mother, who loved and protected without wavering, writer Andrew Lam also recounts a page from Vietnam’s history.

I have lectured at many universities, and I can usually speak without notes, but on this occasion, the saddest in my life, I don’t think I can speak a word without having written it down.

But first, my family and I want to thank everyone who gathered here today to honor our mother. I am sure she fed many of you from one time or another, and hugged a few, and told many a good story, and to a small privileged few, she might have scolded you, telling you to behave and to be good . . .

Many years ago one of my mentors, Professor Franz Schurman, and I were discussing the Vietnam War and its horrors. He said something along this line: “Men stand at the ready for battle, at the door of death, but women . . . they stand at the tree of life.”

I knew he was talking metaphorically, that these are archetypes of the sexes that form our world, but I of course immediately thought of my father and my mother.

My father fought in the Vietnam War for twenty-five years, fought until its bitter end. He saw enough death and destruction to last several lifetimes.

And my mother? She grew up in north Vietnam and experienced war and famine, and then she was part of a mass exodus south in 1954 that divided Vietnam in half, followed by a long, drawn-out civil war.

Born in 1932 to a well-to-do family in Thái Bình, Vietnam, my mother remembered peasants who came into her city during the famine of 1945, begging for food. She was twelve going on thirteen. Since her father had safekept a lot of rice, my mother and her older brother decided to make porridge. They made thin gruel, and in the morning they scooped as much as they could from their big family pot and fed those who begged near their house. They kept doing it for weeks.

My mother saw dead bodies being scooped up each day on the streets and being carted away. She saw a child sitting up on a pile of dead bodies only to lie back down to die. She saw the police whipping a crazed woman who ate parts of a child under a bridge.

But in her retelling, it was the porridge-making that she remembered the most, and the satisfaction she got from being able to feed the hungry.

To feed, to nurture, to protect. To react to harsh reality with kindness and generosity—this is the very essence of my mother.

To feed, to nurture, to protect. To react to harsh reality with kindness and generosity—this is the very essence of my mother.

It made sense, then, that when she moved south and married my father, an army officer of South Vietnam who became a general when I was born, she would wield her powers as a general’s wife to do something for the poor and the needy.

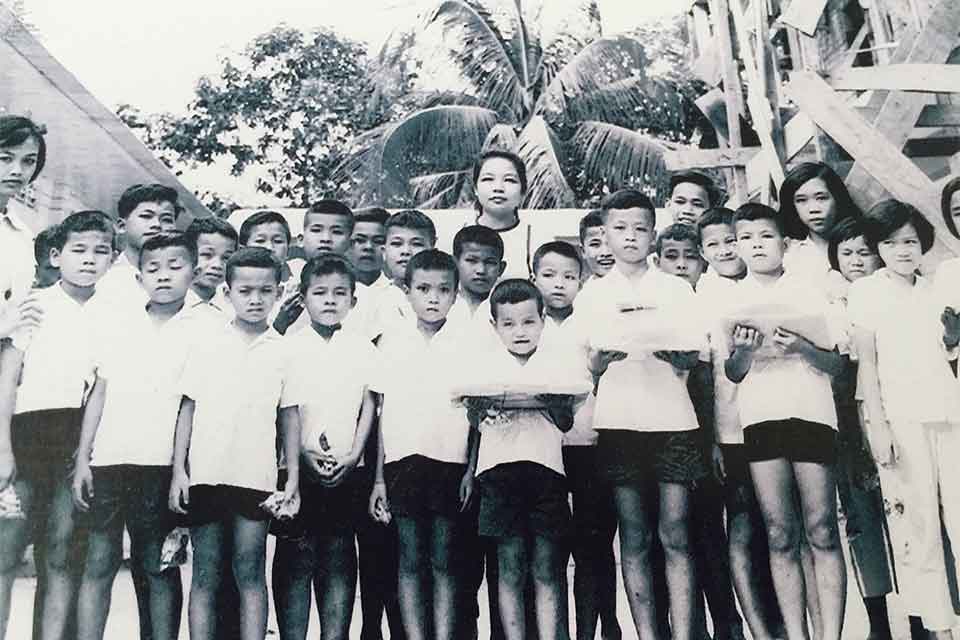

It was in Sa Dec, deep in the Mekong Delta, where she built an orphanage. She fundraised and cajoled and coaxed the powerful and the rich in the region to donate resources and money and land, and soon there it was: two buildings to house orphans and a kitchen in the middle.

I remember how those kids kept calling her mẹ, Vietnamese for Mother. And at four, I remember weeping. “But she’s not your mother,” I would yell. “She’s my mother.”

Of course, she was in many ways the closest thing to being a mother to those kids. She housed and fed them. She ate and sang with them. She sent them to school. Over time she even managed to send some to higher education, and two even made it to Switzerland, on scholarship, near the end of the war.

And yes, one later became a doctor in America—the only person, my mother pointed out to me, who called her mother “that actually became a doctor.”

When the battles got worse, and hospitals were full during the Tet Offensive, my mother converted half of the orphanage into a makeshift hospital. There she and the nurses and social workers tended to wounded soldiers, and one of her aides met a wounded captain, and they fell in love. My mother, of course, officiated the wedding.

The tree of life.

To love, to protect—my mother never wavered. I used to think of my father in heroic lights as a child. He who flew in helicopters and who called bombs to fall from the sky, and he jumped down to earth in a parachute—he was like a thunder god, like James Bond, but my mother? Well, she was a true lioness. And when it comes to her family, she was fearless.

Near the end of the war, my father and his army were forced to retreat south from the city of Hue near the DMZ where he was in command. They took amphibious boats south to Da Nang, and the evacuation was difficult. Many died.

Not knowing if he was alive or not, my mother flew out to Da Nang from Saigon, and she didn’t come empty-handed: no, she brought with her dozens of chickens from the farm we owned on the outskirts of Saigon. And she brought rice.

Behind her, rockets rained down from the Hai Van pass onto Danang, killing people, but mother had cooking to do.

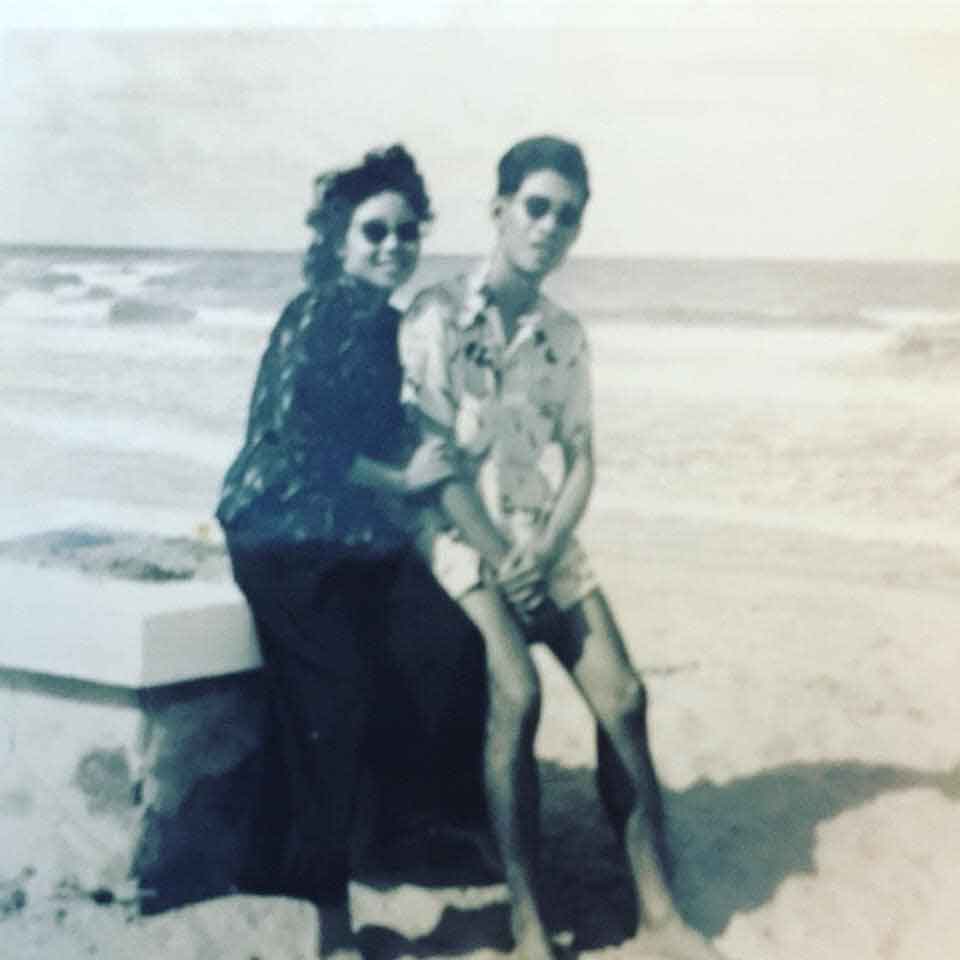

Behind her, rockets rained down from the Hải Vân Pass onto Da Nang, killing people, but Mother had cooking to do. Under the coconut trees by the beach of the naval base, she set up a makeshift kitchen and waited for her husband and his army to come in. The lady general commanded a few sailors to start building fires, and together they made chicken porridge in big steel drums. And when those landing crafts carrying troops came in, with the men all ravished from hunger and weakened by several days at sea—my mother fed them all.

“Your father was shocked. He didn’t expect me to be there,” she would later recall, laughing. “But he was so weak that his soldiers had to drag him to shore.” Then she’d laugh some more thinking of the soldiers that she managed to feed. “You should see the faces of those young men. The way they ate the porridge. They say, ‘Madam, you saved our lives.’”

As a journalist and writer, I have written about the trauma that people experienced due to wars and their aftermath, how it caused many to fall apart in domestic life, to addiction and alcohol. But often I wondered about my mother. How is it that my mother managed to remain so cheerful and highly functional in the face of all the death and destruction that defined so much of her life in Vietnam, and why didn’t those memories of war haunt her in America?

Then it occurred to me that that impulse to protect, that instinct to nurture and save, to put the self in service of others—it formed the very core and spirit of who she was, and it turned out to be her own best medicine against grief. War and death and sadness didn’t own her. In many ways, she owned them: she was always an active agent in the face of calamity.

That is to say, she was busy making soup.

***

And then the war ended, and it ended badly. The South lost, and like everyone else who fled as refugees to America, my family lost everything.

We had to start from scratch.

My mother and her sister started working in a hole-in-the-wall restaurant on top of the hill in Daly City, California. My teenage sister helped. My eldest brother worked in a supermarket across the street, and he helped support us, too, with his meager income while going to high school. I was too young to do anything but sulk and feel bereft and abandoned. I had nightmares. I missed my father, who had stayed behind.

Then, soon after we came to America, news came that my father had made it out of Vietnam, having escaped after us by boat. We rejoiced. We celebrated. He’d survived. But when he arrived he was a changed man—thin and dark and brooding. And he was a broken man, a defeated man.

Traumatized and haunted by the losses and having seen so much bloodshed, he sat in his bedroom and brooded. Sometime in the evening he would come out to watch the news in the living room—he listened to Walter Cronkite telling him more bad news—and drank his whiskey and soda on ice. Then he’d retreat to his bedroom in silence.

Sometimes he would join us for dinner. Other times he ate alone.

He was more or less immobilized by the horror and losses, the humiliation of defeat. That door of death and despair didn’t shut after the war. It was beckoning him.

My mother fretted. But after a year or so, she’d had enough. Losing a country and struggling to survive in poverty in another with three children was stressful enough, but on top of it all, here was a husband incapacitated by ghosts.

One night, a furious fight broke out between my parents.

In that little apartment above the restaurant where she toiled, there was a lot of yelling. “Shape up,” she was screaming at him. “Wake up from this damn stupor!” She threatened to take the children and leave him all alone if he didn’t.

This, mind you, was a woman who earlier—in another country—risked her own life in a war zone and waited on a beach to feed her husband when he swam to shore. A few more fights, and soon after that things patched up between them, and then late one night, as I slept in the dining room wrapped in a beat-up sleeping bag on a little cot, I heard my parents talking above me.

“Swear to me,” she whispered. “You swear to me you will fight to get us out of poverty. Anh the di . . . You swear to me you will do everything in your power to keep our family fed. Restore us, make us whole again so that this little boy can grow up happy.”

My father took his time, then he said: “I swear to you. I will make sure our children will be provided for.”

I remember that moment well. I lay there pretending to be asleep, but I quietly wept. I never shared it with anyone until now, not even with my siblings. But in that moment I knew: my mother was casting her magic spell. On one level, she was trying to save her family or her marriage, but on a deeper level, she was in fact risking the unity of her family—that which she treasured above all else—in order to save my father once more.

She was steering his gaze away from all the specters of war, steering it toward a brighter future in America—the promise of a good life. In essence, she was saying: “Look away from the ghosts and stand with me. Stand with me under this tree of life. Let us tend to it. Let it bear fruit. Let’s make us whole again!”

And he did all that he swore to my mother.

Not long after that night, he got a job at a Bank of America. He studied and got a BA in political science; he studied in night school and, through herculean efforts, got an MBA and, over time, became an assistant VP in the trust department at the bank. After fighting a war in another country for twenty-five years, he was climbing the corporate ladder in another, a remarkable feat unheard of among his contemporaries.

His first check and he bought me three albums that hold stamps. I had escaped Vietnam with my treasured stamp collection in a plastic bag, but the heavy albums that housed them had to stay behind. The gifts shocked and delighted me on many levels. A home for my beautiful stamps at last. I spent months arranging them, and it brought me infinite joy. Because deep down I knew—my father was indeed fulfilling his promises to my mother . . . and I was, like my precious stamps, home.

***

Preparing for today’s occasion, my family and I looked at a myriad of photos that spanned the years, and as I looked through them, the story they tell is not one of sadness but of celebration, of a happy life.

The images in America span a good part of over four decades, and they tell of housewarming parties, of weddings and graduations and many a birthday party, not to mention the various European and Mexican vacations and cruises. Altogether the images bear witness to our ascendancy from that humble beginning as refugees from Vietnam, a sort of American dream, Vietnamese style.

And as I sorted through all those images that spanned the many happy years, I swear to you, I could almost hear my mother’s laughter ringing clear and loud—for she knew she’d triumphed.

***

I wish I could share more about my mother, but there just isn’t enough time.

What I can tell you is this: Alzheimer’s slowly took away pieces of my mother until there was nothing left of the once beautiful and vivacious woman.

Yet as I watched her disappear over the years, I marveled at the miracle that was my mother: even as she forgot who she was, and who I was, she remained true to her nature. Uneaten rice was thrown onto the balcony to feed robins and pigeons that made a habit of visiting her each morning. Potted plants died not from neglect but because, well, with no short-term memories and bad eyesight, she overwatered them. (Eventually we got her plastic orchids, and she, no longer knowing the difference, watered them too and was so proud of how beautiful they bloomed each morning.)

A few times when she could still walk by herself she disappeared, and this caused my father to panic—but mother had to go around looking for a family of stray cats in the neighborhood that she wanted to feed. So, one morning I accompanied her, and as we walked down the block I kept thinking: how does someone who forgets where she lives, who struggles to remember her own name, remember that there is a stray cat and her kittens nearby that needs her to feed them?

A passerby may see a thin and frail old woman feeding little kittens, but that was not what I saw that morning. What I saw was the divine expressing itself through those trembling hands that caressed the hungry and the weak. What I saw was the miracle called love made flesh. And it was sublime.

What I saw was the divine expressing itself through those trembling hands that caressed the hungry and the weak.

***

And so all things born must die, ashes to ashes, as they say, dust to dust. Yet ceaselessly the heavens pour love into our temporal world; and when manifested through human kindness and compassion, it insulates and it uplifts and it nurtures all beings who suffer.

She did not know it, but all those years ago when my mother cast her spell on my father, it also fell on me. In that moment, I knew deep in my heart that I was truly loved, and loved unconditionally, and so I was also free. Free to run far, free to travel the world. Free to fall deeply in love. Free to suffer heartbreaks and self-doubts and failures. Free to triumph. Because every time I looked back I’d see my parents standing there by that boy’s bed, professing their love.

That magic continues to express itself to this day—and now I wish to share it with all who gathered here to honor my mother’s passing, all who descended from her and are bound by kinship and love and kindness, and all who lost loved ones . . . all within the reach of my voice.

First of all, when things get tough, remember to make soup. And, if you can, feed the hungry.

More importantly, open your heart, live in service of others, stand with all your strength, with all your courage for life and living, even in the face of darkness and despair, stand under the tree of life.

Keep loving, even if it might seem at times the hardest thing to do. Despite all your sadness and tears, stand steadfast under that tree and tend to it and watch it blossom and bear fruits.

Stand until the very last light, and you’ll never, ever be standing alone.

San Francisco

She loved to sing. She sang while working in the kitchen or else she sang in her little garden. She remembered songs from her childhood even as the names of her family faded.

She loved to sing. She sang while working in the kitchen or else she sang in her little garden. She remembered songs from her childhood even as the names of her family faded.- She would never admit that she was wrong. She could be sarcastic when corrected. “Of course, you went to Berkeley—that’s why you know everything.”

- She was a great cook. And instead of saying, “I love you,” or “I am sorry,” she would say, “I fried a fish for you. Eat.” And you knew better than to say no. So, even when not hungry, you ate.

- She was a devout Buddhist. Until her health failed her, she lit incense and prayed to Buddha and the ancestors nightly. And what did she pray for? Always the same thing: protection and prosperity for her family and clan.

- She knew how to use a gun. And yes she used it. She once shot at my father for cheating on her with a third-rate singer with big boobs. Somewhere in Dalat, Vietnam, in an old villa on a windblown hill, there surely is still a hole on the wooden floor where the bullet once lodged.

- Strong-willed and feisty, she threw tantrums when she was younger. Hurricane Katrina had nothing on my mother when she was in menopause.

- She once chopped a chicken so hard in anger that its head flew out from the kitchen and bit me on the ankle in the living room. A good fifteen feet. To this day I am the only person I know who was ever injured by a dead chicken.

- She was a great storyteller, and people would be mesmerized by the stories she told. And she could change the details on the fly so as to have the best effects on the listeners.

- She took the bus every day to go to the convalescent home to visit her mother and mother-in-law in retirement. And she fed them Vietnamese food.

- She would come alive when relatives visited her. She was happiest when she was with her sisters and brothers, children and nieces and nephews. Their laughter often blended in with her own.

- She absolutely adored her grandchildren. She found renewed joy and energy in life in retirement, and she and my father were doting grandparents.