The Right to Be a Selfish Woman: A Conversation with Rita Chang-Eppig

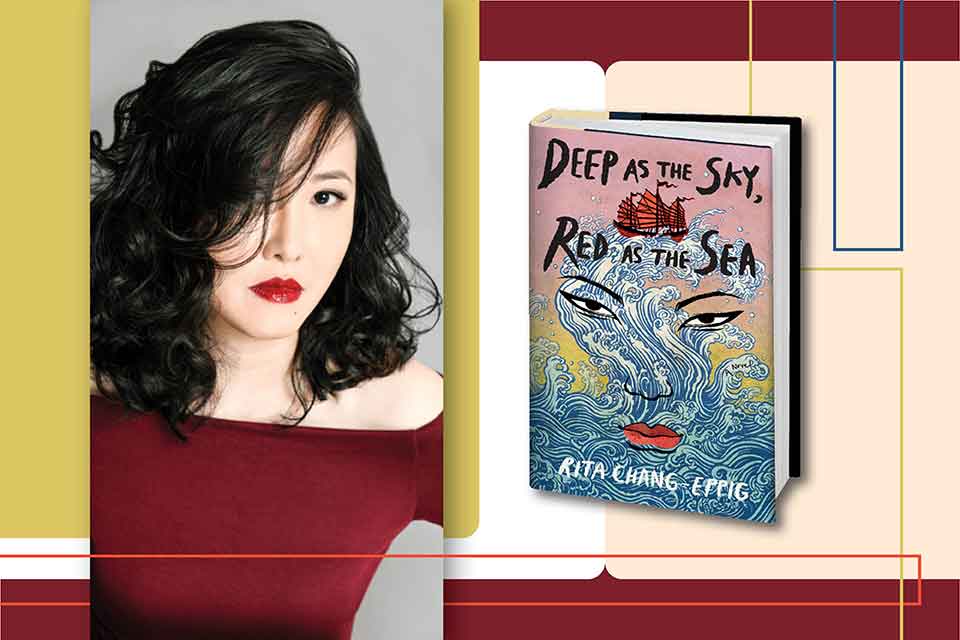

Rita Chang-Eppig’s debut novel, Deep as the Sky, Red as the Sea, tells the story of a woman who fights to survive and the cost that survival demands. Based on the real life of a Chinese pirate queen named Shek Yeung, Chang-Eppig’s novel satisfies my hunger for stories about women who are as ruthless as they are caring. I was delighted to speak with Chang-Eppig about the formidable figure of Shek Yeung, the writing and publishing of Deep as the Sky, Red as the Sea, and our mutual desire for more stories that treat women characters as fully human.

Rita Chang-Eppig’s debut novel, Deep as the Sky, Red as the Sea, tells the story of a woman who fights to survive and the cost that survival demands. Based on the real life of a Chinese pirate queen named Shek Yeung, Chang-Eppig’s novel satisfies my hunger for stories about women who are as ruthless as they are caring. I was delighted to speak with Chang-Eppig about the formidable figure of Shek Yeung, the writing and publishing of Deep as the Sky, Red as the Sea, and our mutual desire for more stories that treat women characters as fully human.

Emily Doyle: How did your idea for Deep as the Sky, Red as the Sea begin?

Rita Chang-Eppig: I grew up in Taiwan, and since I was a child, I’d heard about Shek Yeung. I knew I wanted to write a novel about her, but I didn’t have the heart of the story until the year 2019. Back then, my mother was diagnosed with an aggressive form of uterine cancer (thankfully she’s recovered now). And this is going to sound so weird, but I remember sitting in the hospital waiting room on the day of her surgery and on every single TV, Notre-Dame was burning down. It was surreal to watch this beloved historical site—the name of which translates to “Our Mother” or “Our Lady”—burn while I wasn’t sure if my own mother would make it through her surgery. Then a couple of weeks later, I was doing some research for the novel, and I learned how Shek Yeung had worshipped a sea goddess named Ma-Zou, which translates to “Maternal Ancestor.” That’s when it all clicked for me.

Yes, Deep as the Sky, Red as the Sea is about a woman pirate, which is exciting. But it’s also about the ways in which women, even if they don’t have children of their own, mother one another despite horrific circumstances.

Doyle: I’m intrigued to learn that Deep as the Sky, Red as the Sea started with your mother, considering Shek Yeung’s own relationship to motherhood. Throughout the novel, she seems to choose her life as a pirate commander over her children. To be honest, this excited me—not because I was glad she was leaving her children behind, but because she was one of the few mothers I’d encountered in any story who wasn’t ready to sacrifice herself for her children. Can you speak to Shek Yeung’s motherhood?

Chang-Eppig: I’m using the word “mother” in a conceptual way. For me, motherhood is a much broader idea than the parenting of a biological child. Although Shek Yeung makes a bunch of terrible decisions along the way, she is a mother to her fleet. She feels she needs to lead them through a treacherous world.

Of course, motherhood is also really complicated. Like you, I tend to get annoyed when I see or read depictions of motherhood that imply all mothers are these perfect nurturing vessels who will choose their children over everything. Our society’s concept of motherhood needs to expand.

Our society’s concept of motherhood needs to expand.

Doyle: Part of me found Shek Yeung’s relationship with violence and power exhilarating as well. At the same time, I understood she’s pressured into action by desperate circumstances. I suspect I recognized a character who was not being put into a box of womanhood, or was at least pointing at that box and asking, “Whom do you serve?” Do you view Shek Yeung as a counterweight to representations of women, especially Asian women, in literature? If not, how do you see her?

Chang-Eppig: Like Shek Yeung, most people are capable of violence if things in their lives work out a certain way. So, she’s definitely a counterweight to one depiction of Asian diaspora women as meek victims. I didn’t write with that intent, though. I was really just trying to consider what I think the average human being would be capable of doing if everything in their life went horribly wrong. In Shek Yeung’s case, she manages to become powerful through violence.

When I think about power, I think of that alchemical image, the ouroboros, of the snake eating its own tail. Power is like that. It’s a thing that creates a need for itself. Still, I wanted to explore the ways in which power benefits Shek Yeung. For instance, as a child, she’s a poor peasant girl who’s then trafficked onto the flower boats. Once she gets power from her first husband, Cheng Yat, her life improves. At the same time, the threat of losing her power haunts her because she fears returning to the way things were.

But in a very simple way, Wo-Yuet, a woman Shek Yeung befriends before becoming a pirate, is Shek Yeung’s moral compass. She knew Shek Yeung when she was just trying to get through each day. She’s the only person who’s able to call her on her bullshit. After she’s gone, Shek Yeung becomes more destructive.

Power is like that. It’s a thing that creates a need for itself.

Doyle: Shek Yeung’s response to Wo-Yuet’s absence makes me wonder about your concept of character. That is, when you’re developing characters, do you think of them as individuals, part of a collective, or maybe a mix of both?

Chang-Eppig: On one hand, there are studies that show you can very often tell what kind of personality people are going to have as adults just by observing how they are as babies. So, it seems that there are some parts of personality that persist. On the other hand, it would be strange to suggest that we’re not all affected by what happens to us.

Fundamentally, Shek Yeung’s willful and proud. But if not for some of the adversities she experienced, her personality might have manifested in a completely different way. I think we’re all born with fundamental traits, but the environment brings certain things out in us. It’s a cop-out answer, but I think it’s both.

Doyle: I don’t think that’s a cop-out answer; it seems true to me, too. As you’ve mentioned, Shek Yeung is based on a historical figure. She’s been called many names: Zheng Yi Sao, Ching Shih, and her birth name, which is Shi Yang in Mandarin and Shek Yeung in Cantonese. How did you arrive at the name Shek Yeung?

Chang-Eppig: The names most commonly used to refer to Shek Yeung—Zheng Yi Sao and Ching Shih—both translate to “Cheng’s wife.” Many women of her time were not given their own names but were referred to by their relationship to the most visible man in their lives. As you might imagine, when I started writing this novel I was like, “Absolutely not.” So I went with the Cantonese version of her name, Shek Yeung.

I decided not to go with the Mandarin version because Shek Yeung and the other people in the novel lived and operated out of southern China, where Cantonese was the dominant language. In a way, I was trying to give her name back to her.

Doyle: I’m so glad you were able to. Relatedly, how much freedom did you feel or not feel in writing about Shek Yeung given that she’s based on a real person?

Chang-Eppig: I felt beholden to certain facts about her life. For example, before she became a pirate, she was a sex worker or victim of trafficking, depending on which version of history you listen to. There was a part of me that didn’t want yet another depiction of an Asian woman sex worker out there. So, I considered not making her one. But then I thought about how I didn’t want to contribute to the erasure of sex workers, because for some people sex work is absolutely a choice. And I didn’t want to pretend like that aspect of her life wasn’t important.

There are also other easily verifiable details, like who she married and her fleet’s exploits throughout Asia. Those I felt obligated to maintain. That said, I felt free to make up her interpersonal relationships, decisions, and psychology because those things are usually lost to history. This is the beauty of historical fiction: history gives us the skeleton, and fiction fills in the organs, the blood, the heart.

This is the beauty of historical fiction: history gives us the skeleton, and fiction fills in the organs, the blood, the heart.

Doyle: I’m curious about your thoughts on “realism” as a literary genre. As you’ve mentioned, Shek Yeung is a worshiper of Ma-Zou, the sea goddess. We like to talk about literature as if there are clear divisions between realism and everything else. But Shek Yeung believes in gods as much as she believes in the ocean tides. In my mind, to exclude from her perspective her experiences with Ma-Zou would be unrealistic. Are there ways in which realism is rooted in contemporary white European and European American realities, to the exclusion of other realities?

Chang-Eppig: Yes to everything you’re saying. And I’m going to add another layer.

Doyle: Please do.

Chang-Eppig: I read a relatively recent study done in the United States in which people were asked, “Has God ever spoken to you?” Something like 25 to 30 percent of people said yes. When I saw that, I started thinking about how the boundaries of reality are slippery for a lot of people, past and present. I wanted to play with that line to accurately represent Shek Yeung’s experiences.

I do think that there’s a cultural component as well. In modern-day European and European American traditions, how do fairy tales usually start?

Doyle: Once upon a time.

Chang-Eppig: Yes, “once upon a time” or “in a land far, far away.” Something like that. These openings are usually meant to distance the reader or listener from the story. But there’s a very old collection of anecdotes by Pu Songling called Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio. Its stories often reference ghosts, gremlins, and deities. Yet every one of them starts with details seemingly meant to prove their authenticity. There’s this sense that spiritual experiences are very much a part of reality.

Doyle: I want to read that text. What a gift.

I’m also curious about what your experience publishing Deep as the Sky, Red as the Sea has been like. As your novel has approached its publication date, have you undergone moments of misunderstanding or clarity? Of loneliness or connection?

Chang-Eppig: I’ve experienced loneliness, which is funny because I know many people who have published books. But at the same time, they’re not going through the process at this exact moment. In that sense, I’m going through it alone.

I think I’m going to look back on this year as a wild and fun ride. But while I’m in the middle of it, I just feel like I’m trying to hold on to a roller coaster bar and not get flung out. For right now I feel incredibly grateful, and also really anxious and overwhelmed by everything that is happening and is going to happen.

Doyle: Well, I’m excited because I know how wonderful the novel is, and how much I personally needed Shek Yeung’s story in my life.

Chang-Eppig: I know that I’m asking you a question now, but do you mind saying more about that?

Doyle: I resonate with Shek Yeung’s fighting spirit, even as it leads her to do some terrible things. I needed to see how far she would go. It’s not that I’d sign off on all her actions from a moral standpoint. But did I love her journey? Absolutely. Did I find her story valuable? Yes. That’s what I mean when I say I needed this story. It’s not even for me, really. It’s for everyone, and I think you wrote it for yourself, too.

Chang-Eppig: I’m really glad you’re saying that because I think women are often not allowed to be selfish. Do you know what I mean?

Doyle: Yes.

I don’t find female characters who are perfectly loving or kind very believable.

Chang-Eppig: We’re not allowed to be selfish in life. We’re not allowed to be selfish in literature. But the fact of the matter is, I think we’re all a little bit selfish. It’s not an accurate representation of being human to suggest that women are these perfect, loving creatures.

When I was writing about Shek Yeung, I wasn’t trying to make her a villain, but at the same time I didn’t want to pretend she cared for everybody. I wanted her to have an edge, a little bit of meanness. Because I think that’s present in everyone. And I’m not sure how much I’m going to regret saying this, but I don’t find female characters who are perfectly loving or kind very believable.

March 2023

Rita Chang-Eppig received her MFA in fiction from NYU. Her stories have appeared in McSweeney’s Quarterly Concern, Conjunctions, Clarkesworld, The Rumpus, Virginia Quarterly Review, Best American Short Stories 2021, and elsewhere. She has received fellowships from the Rona Jaffe Foundation, the Vermont Studio Center, the Writers Grotto, the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, and the Martha Heasley Cox Center for Steinbeck Studies at San Jose State University.