No Place for Women

For the past few years I’ve been living in Lahore. Like they have for many, the brave women-led Iranian protests have made me reflect on the rights of women and the price we pay for freedom and justice. With this in mind, I decided to visit the Lahore High Courts to see what it was like for women living here.

For the past few years I’ve been living in Lahore. Like they have for many, the brave women-led Iranian protests have made me reflect on the rights of women and the price we pay for freedom and justice. With this in mind, I decided to visit the Lahore High Courts to see what it was like for women living here.

So as to remain inconspicuous, a friend suggested I dress like a lawyer in a white salwar kameez and black coat. As I got ready that morning, I recalled the last time I’d been in a courtroom was over twenty years ago while working as a lawyer in Kenya.

As we drove through the streets of Lahore, the December sky was a cloudless, dull gray, there was heavy smog, and the roads were jammed with traffic. Pigeons sat like guardians on the electricity wires crisscrossing the city. A man with a basket at the roundabout shouted in a raucous voice for passers-by to buy his boiled eggs.

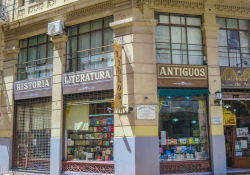

The iconic red-brick High Court building sits in the shadow of Anarkali and the general post office on Mall Road and was built in 1889 by the British in Indo-Saracenic style. The main materials used in its construction were brick masonry, kankar-lime mortar, Nowshera pink marble, and terracotta jaali. It is an imposing building, signaling the weight and might of the law.

The High Court is an imposing building, signaling the weight and might of the law.

I made my way through the tall gates to the main courtyard and found a well-landscaped compound; tall, leafy trees and walkways lined with flowers and low bushes. But despite the greenery, the atmosphere was taut; a mood of expectation tinged with a premonition of disappointment. The place had a strange energy—a feeling of paralysis and listlessness, on one hand, and a preying, animalistic aggression on the other.

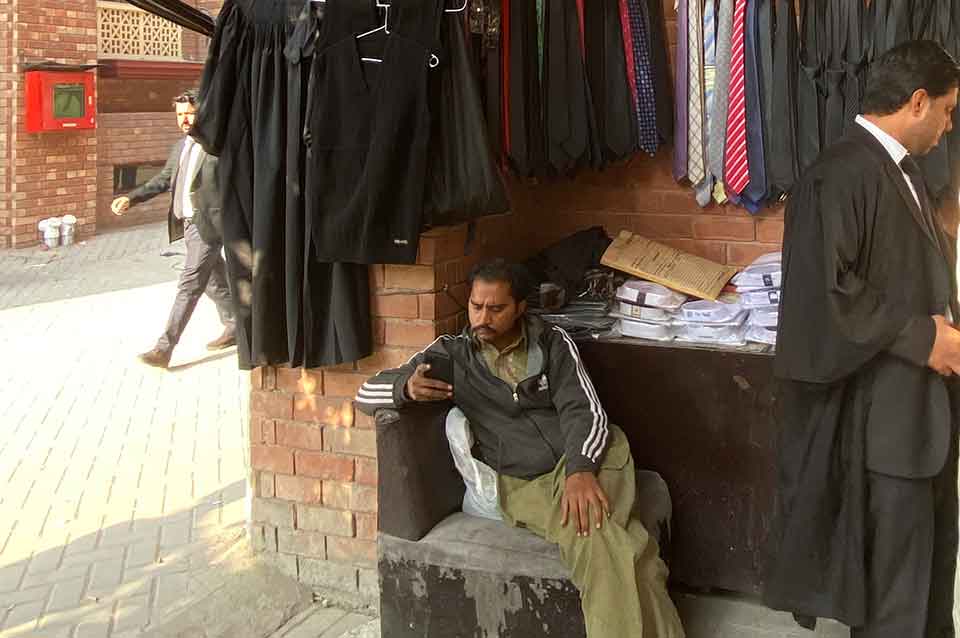

The High Court sessions began at nine and I was early, so I took the time to look around. In a corner opposite the main building from a small kiosk a man was selling lawyers’ gowns, white shirts, striped ties, and black shoes. I was surprised. Were the garbs of a lawyer like an actor’s costume that any man could buy for a few hundred rupees? I became conscious that I too, that morning, was acting and impersonating.

I went over and asked the man if there were clothes for women lawyers, for instance a white salwar kameez and coat?

The man looked at me like I was stupid. “This is a lawyers’ shop,” he said. “Get your things from Anarkali. But I can give you a black gown, it’s on sale today.”

I did not try to explain what I meant.

The morning sun cast a warm glow on the gardens, and watching the moving shadows of the men passing under the arches made me think of how many thousands must have walked under them with dreams of receiving justice.

I thought I should get a cup of tea while I waited and made my way to the tea area. This was an open space under a corrugated iron roof with rows of benches. Men sat sipping tea and gossiping, their bellies bursting in too-tight suits. On their feet they had only socks, while nearby a man in shabby clothes was on his knees polishing their shoes.

A man shouted for him to hurry up. The shoe-shiner carried on his brushing. “I’m doing my best, but your shoes are filthy.”

The man laughed. “What do you expect? The law’s a dirty business.”

I stopped a man serving tea and asked if I could get a cup. He gave me an irritated look and pointed to a door. “That’s the women’s room.”

That was when I realized everywhere I looked I’d seen only men. Men in their lawyer’s gowns talking on the phone or to each other. Male clerks carrying books. Men rushing around with desperate faces.

I looked more carefully. Twenty minutes later I’d counted ten female lawyers. They were dressed as I was, their faces serious and determined. But where were the female plaintiffs and defendants? The female witnesses and clerks? I smiled at one lawyer, hoping to start a conversation, but she gave me a blank look.

Inside the women’s room, I found a table and a tired-looking sofa. On the wall was a portrait of Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the first governor-general of Pakistan, who was a lawyer, a discolored image of the Pakistan flag, and a wooden sign: Unity, Faith, Discipline.

No women except for one wiping the furniture. “You can wait in the bar room,” she said, without any expression. I wanted to ask her what happened to all the women but felt from her tone she was telling me to leave her alone, so I did as she said.

The bar room had a high ceiling and tables with leather chairs arranged like a dining room. A few men in suits were reading the newspaper and watching the sports highlights on a large television screen. An old man swept the floors and wiped the tables. On the walls, a large gold-framed photo of Jinnah, a clock, the image of the flag, and the same slogan. I sat by the door and waited until I heard someone shouting the courts were in session. No one so much as glanced at me.

The entrance to the main High Court building was crowded with men. Then six large military trucks drove up, and hundreds of uniformed antiriot police jumped out carrying shields, batons, and guns. They seemed to be in a jovial mood as they surrounded the building, helping each other adjust their belts and helmets. It didn’t seem like they had come prepared to fight but were just carrying out a routine role-play. I learned, from a passing stranger, the legal fraternity were on strike because a judge had criticized a lawyer for putting on his gown in court and held him in contempt.

I went into a courtroom. It had a teak ceiling with quarter-arched corners and arched windows. The observers’ gallery had dark, well-polished teak benches, and the floor was white marble. Around the room was a row of unsmiling portraits of every high court judge since the High Court was established; white and brown men. Not a single female face.

Around the room was a row of unsmiling portraits of every high court judge since the High Court was established; white and brown men. Not a single female face.

At the front sat a male judge in his black gown and red band. Bald and bespectacled, he discussed something with two male lawyers. One kept turning the pages in his file. Behind them were two men with grandly tied turbans reminiscent of Mughal times. They passed the judge files, and two others took notes. The judge raised his voice and pointed to a section. A lawyer responded and showed him a book. That was the wrong clause, the judge replied. Another lawyer held out a file. The judge lost his patience.

“It’s irrelevant,” he said. “That’s not how the law works.” He adjourned the case.

The turbaned man went to the door, called out a name, and two more lawyers entered with their clerks carrying huge bundles of files. The same thing happened. The judge and lawyers argued, the judge became annoyed, the case was adjourned. Not a single case was brought by a female lawyer. No one in the courtroom was female except me.

I asked the man sitting beside me, “Where are all the women?”

He gave me a confused stare and put his finger on his lips.

Feeling suffocated, I went to the door, but at the same time six men wanted to enter. They did not make way but pushed forwarrd. It was as though I was invisible. To reassure myself I was not, I greeted a guard sitting outside the courtroom. His expression did not change, and he carried on smoking. Embarrassed, I looked away.

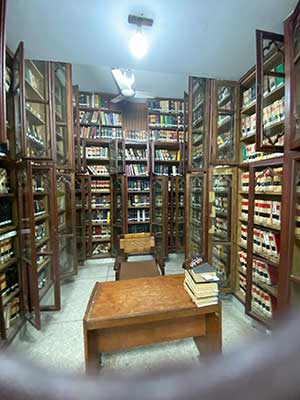

I made my way to the library. . . . I did not find a single book by a female author.

I made my way to the library, a fair-sized room with cabinets along the walls and tables and chairs. On the tables were small wooden signs. On one side it said, Please be nice to staff; on the reverse it said, Please observe silence. The librarian was male, and a few men were lounging there scrolling their phones. Not a woman in sight. The books were arranged in no particular order. I browsed through a few and discovered from the markings on the inside covers they had been donated by defunct law firms and retired lawyers. I did not find a single book by a female author.

Back in the corridor, I waited in the sunlight coming through the arches for a man to say, Excuse me, you’re blocking the path. But none did. They brushed past me, walked around me, and made me move out of the way when they were in a group. I wandered down the hall. Outside every office was a plaque with the name of a man. I checked the plaques outside twenty doors; not a single one had a woman’s name.

I went back to the man in the kiosk selling clothes and asked him, “Why are there so few women lawyers?”

“Obviously, because women don’t have problems,” he said. “Why else?”

I asked a security guard standing near the door, “Where are all the women?”

“This isn’t a safe place for them,” he said. “You shouldn’t be here either. Can’t you see how many police there are here today?”

As I exited the gates of the High Court compound, I met a woman selling pencils and notebooks. Her face was wrinkled and tanned because of long hours of exposure in the sun and cold. I asked her if she’d ever been inside the High Court.

“Never,” she said. “It’s mainly for big, rich men who come here to fight for their money and land.”

I tried to tell her what the buildings stood for—equal justice for men and women, rights especially for women, the rule of law for all citizens.

She shook her head. “That’s not how it is here. You must be a foreigner.”

London / Lahore