A Conversation with Carsten Jensen

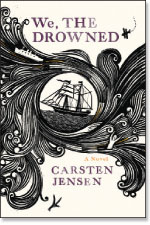

Carsten Jensen (b. 1952) is a Danish novelist, essayist, and critic who writes for the Copenhagen daily Politiken and serves as a commentator for Danish television. Born in Marstal in 1952, he studied literature at Copenhagen University. His three fictional works include Earth in the Mouth (1994), We, the Drowned (2010), and Sidste rejse(2007; The last trip). He has also authored a number of travelogues, of which I Have Seen the World Begin (2000) is available in English. In 2009 he was awarded the Olaf Palme Prize for outstanding achievement.

Ray Taras: Among favorite stories about the sea written by Scandinavian authors, you have singled out ones written by Hans Kirk (about whom you wrote a dissertation) and Knut Hamsun. Are there other Scandinavian novelists whose literary styles and narrative plots have influenced your writing?

Carsten Jensen: There is actually not a great tradition of maritime novels in Scandinavian literature, strangely enough because we are seafaring nations, especially Norway and Denmark. Writers were never recruited from among sailors, and sailors did not end up as writers in the way that Joseph Conrad did. If you take Kirk's novel The Fishermen, written in 1928, it is about a community of fishermen—and I really distinguish between sailors and fishermen because they lead such different lifestyles and have such different relationships with the sea. Hamsun didn't write maritime novels, but some of his so-called Nordland novels, which take place north of the Polar Circle, are about little ports where sea and ships and trade play a big role, and where sailors are always cosmopolitans—the "baddies"—because Knut Hamsun was very much attached to the soil and to traditions and, as we all know, tragically ended up having Nazi sympathies as well. In his novel August, sailors were not just cosmopolitans but something worse—they were Americanized. They were the symbol of modern soullessness and rootlessness.

In writing a maritime novel, I wanted to know what kind of tradition I was about to become a part of. So the few Scandinavian novels there were I did read. If there is a tradition of maritime novels, it is British and American: Herman Melville, Jack London, Joseph Conrad, and the South Sea tales of Robert Louis Stevenson. You cannot really imitate their style, and I didn't want to. But there are a lot of hidden literary quotes in my novel. Already on the first pages of We, the Drowned I refer to a Melville character who sailed on a man-o-war having the ridiculous name of "Never Sink." I have stolen that name from Melville's novelWhite Jacket. These allusions are intended as little winks at the knowing reader, though it is not really important whether all readers recognize the reference.

I wanted to capture the atmosphere in these maritime novels. The part in my novel about the South Seas, which is the only part told in the first person, is actually the least researched part and also the most adventurous. This is where I feel closest to the mid-nineteenth-century literary tradition of how to describe that exotic part of the world. But there is no tradition about how to describe the convoys that sailed in World War II. What masterpiece is there describing that?

RT: Your first work of nonfiction, I Have Seen the World Begin, foreshadows your commitment to taking an insightful, sensitive approach to intercultural encounters. Did you plan to write such a comparative cultural analysis before you traveled to China, Cambodia, and Vietnam?

CJ: Not at all. I traveled to get away from analyzing. I was quite an established essayist in Denmark, which was not really a Danish genre. Danish literature never liberated itself from late romanticism. Such romanticism does not assume that it is the writer's intellect that is his driving force but, rather, that the writer has a very big heart. So it deals with feelings and emotions, not cold intellect and analysis.

The essay is, if not the opposite, then very far removed from that tradition, so it is not very alive in Danish literature.

I had traveled extensively in Asia before the fall of Communism there. When I returned in the 1990s, rooms that were unknown to you because the doors had been locked were now open, so I entered. I saw these travels as an exercise in the use of the basic skills of a writer: use your eyes and ears, listen and observe. But my travelogue is really a literary hybrid where I mix genres: essay, journalism, and the writing style of the novel.

The English volume is only the first of two and has been drastically shortened, and I had to put up a real fight to feel it was still my book. The second volume takes you across the Pacific to Papua New Guinea and then Latin America. In Papua New Guinea I went to some of the same places along the Sepik River visited by Margaret Mead in the 1920s. Noticing the immense differences in culture and gender patterns from village to village, she came up with the idea that there was no biological given and everything has to do with social structures, especially gender roles. This was her big discovery—that you're not born a woman, you're brought up to be a woman. The ideas of freedom from roles and class, that man is endlessly changeable, were at that time wonderful, liberating ideas. But in the hands of the Stalinists in Russia, they became dogmatic ideas. The "new man" was a totalitarian idea: there were no limits to what you could do to man because he would always adapt.

So I wrote about travels in that part of the world where equality had ruled and where the idea of freedom—in this personal (private) sense, that feminism is an expression of freedom—was discovered by anthropologists.

RT: That book, together with your first novel set in India, were land stories. Earth in the Mouth is as descriptive a title as We, the Drowned. The transition can't be more graphic and evocative.

CJ: The real transformation is seen in the title of my two travel books, which begin with "I," the first-person singular. We, the Drowned begins with the first-person plural because it is a novel about a community. In Danish we even use the expression "community novel." Earth in the Mouth has a double meaning. It signifies death; it is how we end up. But it is also a symbol of an oral narcissism, of wanting to swallow the whole world, to have it in your mouth and taste it, to become one with it, swallow it, digest it. The novel is about a very young man traveling on the subcontinent, and things go very wrong for him. Today I feel it is only a half novel and that I wasn't ambitious enough about it. What I published was like the beginning of a novel. What I would do today is describe in detail the young man's descent into the inferno of the Indian subcontinent and the abandonment of his own self.

RT: The seamen the reader encounters in We, the Drowned are extraordinarily cosmopolitan characters, anchored in a cosmopolitan seafaring culture that blends diverse national and local cultures from around the globe. It is not the negative type of cosmopolitanism described by Hamsun. Nor is it the contrasting parochialism that characterizes the farmers you describe in your novel. Was it your intention to highlight the cosmopolitanism—a much talked about and praised attribute among intellectuals today—of sailors?

CJ: Cosmopolitanism is treated as a positive quality in my novel. I argued with myself: Why don't I simply say this in an essay? What is it that makes it necessary for me to write in a genre—the novel—that I last employed more than ten years ago and that I had somehow abandoned?

Two generations ago, if someone had asked a Dane what kind of nation Denmark is, he would have answered without hesitation, "It is a seafaring nation." If you ask him today he would say, "It is a welfare society," which is of course true. But if you ask him what kind of nation Denmark was historically, he would answer, "We were a nation of farmers." That perception has a lot to do with Denmark's growing nationalism over the past ten years. The seaman is not a convenient figure for a nationalist to identify with. His identity is somehow too mixed. Of course you can find sailors who are racist. It is not that they are all necessarily enlightened; they can be very brutal, not at all open-minded. But as a class they have one very valuable experience: they know there is more than one culture in the world and more than one way to deal with the world. The farmer has never had this experience. For him, the perimeter of his field is the limit of his experience. He has only one world and doesn't travel between several worlds.

If you want to glorify your nation, then the farmer is far more convenient a character than the sailor is. So in my novel I wanted to polemicize, and to remind the Danes, that we were once something else. In an age of globalization, a nation that remembers its seafaring past is much better suited for confronting the imperatives of globalization, which, whether you like it or not, requires that you must learn to live with strangers.

Moreover, sailors are often written out of history. There were six thousand Danish seamen who sailed in convoys during World War II, of whom one thousand never returned home. They are never mentioned in history books. In Norway there were thirty thousand sailors who took part in convoys, yet they don't exist in Norwegian history; they just disappeared. In writing this novel, I took up an overlooked aspect of history. At the same time, my basic objective was to narrate the many amazing stories I discovered in the archives of the local museum. No one had been using them, and I felt that I had all the gold in Klondike to myself.

RT: You regularly presented draft parts of the novel to an audience in the local library in Marstal, where the novel is set. Did your meetings with Marstallers have the character of a writing workshop?

CJ: I did workshop with the people of Marstal over the five years it took to write the novel. I was born there but was also a well-known and public figure in the outside world. I read excerpts from the work in progress. I didn't ask for advice on how to write my book, but I wanted the locals' opinions, and I also needed their information. I thought of it as a kind of trade: you get a book about your town and in turn you give me information. So when the book was launched in Marstal, the town organized a celebration. There was a sailors' choir, the local mayor made a speech, and Danish flags flew along the main streets. There was the feeling that "We have done this together and we are celebrating it together."

Some people told me: "I heard these stories as a child." And I replied: "You can't have because I made them up." What had happened was that fiction and reality had become totally welded. In the mind of the locals, you could no longer tell what was a story from the novel and what was local history.

RT: That is an achievement on your part. I want to ask about two other characters in We, the Drowned. You highlight the danger of going native, as Laurids Madsen does in Samoa. And perhaps the most evocative element of magical realism involves the handing over of the head of Captain Cook from one generation to another. What do these two iconic characters mean to you?

CJ: I don't pass any moral judgment on Laurids Madsen; it is not the job of the writer. His son Albert does, and it has nothing to do with his going native—it is about him as a father. He abandons his family in Marstal and creates a new family in Samoa that is a mirror image of his former one. There actually was a man from Marstal who lived in Samoa in 1873. He was even a friend of Robert Louis Stevenson. He ran a local trading post, went native, and married a local native girl, a Samoan. For the English settlers on the island, this was the worst thing that could be done. A European lost social status if he went native. He could have mistresses, but he could not marry them. Resulting children would be of mixed race, and they would be looked on as outcasts. The way that Laurids Madsen's extended family in Samoa became parasitical was an idea I picked up in a little-known book by Robert Louis Stevenson called A Footnote to History, a short anthropology of Samoa based on his own observations.

Then there is James Cook. I often get the question: What did you make up in the novel and what actually happened? As a general rule, the answer is: The more unlikely it sounds, the surer you can be that it really happened. And the more everyday and commonplace it sounds, the more you can be sure that I made it up. I could find a lot of extraordinary events described in the Marstal archives, but the daily lives I had to invent. So then I'm asked: What about James Cook's shrunken head? And I have to say that that's the exception. I made that up.

The title of the book refers to the presence of death—and what is deader than a shrunken head? Mark Twain inspired me to come up with that idea. He wrote a short book about the Sandwich Islands, Roughing It in the Sandwich Islands, which he visited as a young man. In it he gives a very ironic description of the death of James Cook, whom he clearly doesn't have much respect for. He describes in detail how his dead body was chopped up by the natives and used in different ways— for example, the entrails were smoked. So I asked myself: What about James Cook's head? And I thought: This is where I come in. In the novel the shrunken head is a memento mori, a constant reminder of the presence of death.

RT: How is a drowned sailor memorialized?

CJ: Storytelling involves a beginning and an ending, but for the widows of Marstal whose husbands were lost at sea, there never was an ending. No burial, no ritual of saying goodbye—like a sentence without a period. I felt I was finally providing an ending to their story, bringing the dead back home and burying them. I was constructing a symbolic or metaphorical cemetery.

As one character in the novel explained why he needed to survive a storm at sea, "I want to be buried in the new cemetery."

RT: Your latest novel in Danish, Sidste rejse (The last journey), also focuses on the sea, this time as seen through the eyes of Danish artist Carl Rasmussen. In it you interrogate the meaning of art. How different a novel did you want it to be from We, the Drowned?

CJ: This latest novel is the story of an outsider who wants to enter a community but fails. It is a story about a painter—a child of the Golden Age of Danish painting in the mid- and late-nineteenth century. Painters of that school gave the Danes an image of themselves that we have never outgrown. It is a picture of a small, modest, harmonious nation. It has no great landscapes, no great heroic people. The beauty is to be found in the modesty of everything—the small towns, the intimate details of daily life lived by modest people.

Carl Rasmussen was a member of the second generation of these artists. He gets caught between this traditional art form and the modern, industrializing world and has an artistic crisis. The novel is about a painter who cannot see because narrow-minded ideas of what art is prevent him from seeing reality when it doesn't conform to his ideals. Carl Rasmussen may have met Gauguin, who was married to a Dane and lived on and off in Copenhagen. Gauguin wrote an insightful book attacking the Danish mentality. The two painters meet in my novel. Gauguin's modern canvases are a total shock to Rasmussen, whose works remained traditional. (He was a mediocre painter and has been completely forgotten.)

I made a choice to write a novel about a Danish painter who is mercifully forgotten today. It wasn't his art that interested me but the limitations of his art. In many ways that art reminds me of Denmark today: introverted, conservative, partially blind.

RT: Your fiction does not betray how politically engaged you are in Denmark. How do you resist the temptation to politicize your novels?

CJ: When I write my essays or am invited to speak on television, I feel I have a very immediate impact. I raise my voice whenever there is silence on a political issue that I feel is relevant. The novel is where I explore other ideas, including existential ones. The first section of We, the Drowned describes a battle to take control of a German town in the Schleswig War. I depict these people as being far removed from politics. They don't even understand the word, never mind the purpose of the war.

I am now writing a novel about Danish soldiers in the war in Afghanistan. After I went there I formed a totally different opinion from the official one. But this novel, too, is not intended to be a political lecture about what is right or wrong; it is about men in extreme situations and what it does to them. Novels are about exploring unexplored territory in the human experience or, at least, drawing new maps of old lands.

January 2011