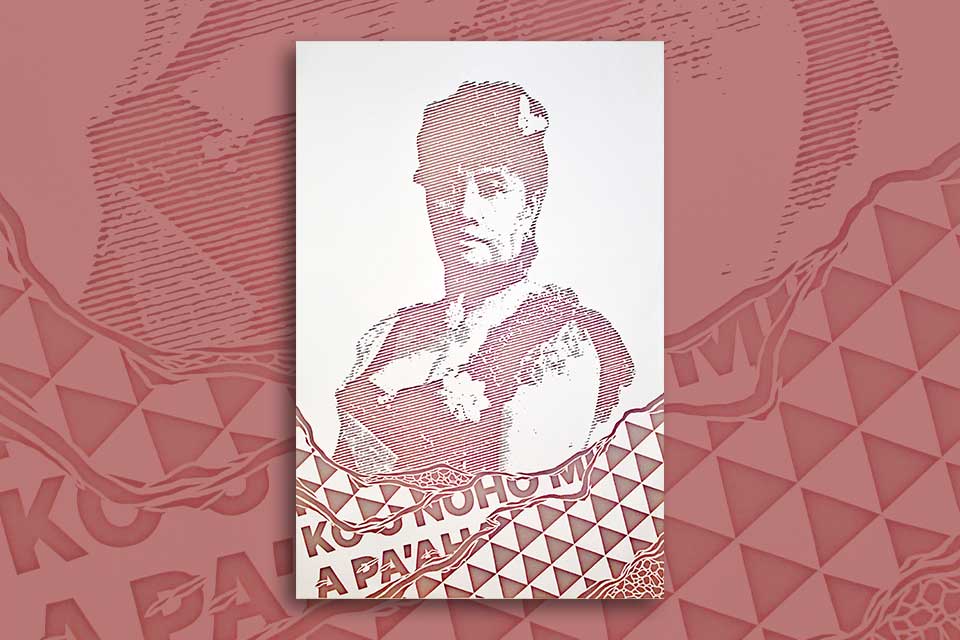

How to Swallow a Colonizer: Or, What I Learned from Haunani-Kay Trask

The following essay was originally delivered as a talk for a virtual poetry workshop for the Department of Race & Resistance Speaker Series at San Francisco State University in 2022.

Gratitude inspires reciprocity.

We build the future together.

And we cannot—should not—build without our ancestors and our mentors.

With humility, I build a bit of future alongside you by expressing aloha for an ʻŌiwi (Hawaiian) poet who loved her country fearlessly.

I am a lifetime student of Haunani-Kay Trask, an ʻŌiwi aloha ʻāina who fought for her lāhui (nation) when both the idea of a sovereign Hawaiʻi and the idea of an ʻŌiwi woman going toe-to-toe against white supremacy and settler patriarchy were unthinkable.

Too often, the truth is that we cannot be what we cannot see. Representation matters.

Our teachers are foundational.

In the summer of 2021, Hawaiʻi mourned, because Haunani-Kay Trask passed from our world.

In 1993, one hundred years after the illegal overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi by a group of American thugs and a ship of American soldiers, Haunani-Kay Trask spoke to a crowd of hundreds of Hawaiians, hungry in all the ways a people can be hungry. “We are not American!” she chanted, gripping the mic. “We are not American! We are not American! We will never be Americans. We will die as Hawaiians.” Haunani taught me how to claim my ancestors without shame.

When I read Haunani’s poetry, I learn how anger, pride, and ecstasy can live on the same page—not as a broken treaty or an eviction notice but as a poem. A poem that can live as a small rock in your chest until you’ve learned how to breathe better, how to dream better, until you’re ready, as Audre Lorde tells us, to transform silence into language and action, ready to spit that rock on the page or the stage, and ready to be, as Haunani taught us, “raw, swift, and deadly.”

When I read Haunani’s poetry, I learn how anger, pride, and ecstasy can live on the same page—not as a broken treaty or an eviction notice but as a poem.

When I read Haunani’s poetry, I learn how to love better. How to stand taller as an aloha ʻāina. How to say “no.” And to trust my “no” as a complete sentence: Not today, colonizer. No.

What do you need help saying no to? Who taught you your “no”? What happens to your body when you say “yes” and mean it? That’s a kind of aloha.

Haunani taught me that aloha is rage and rapture. She taught me the complexity of that “and,” which was all but shamed out of us by missionaries.

As for so many other island nations, the history of missionaries in Hawaiʻi is violent and insidious. The toxic binary between one god brought by foreigners and our many gods born from our ʻāina was a lesson in fear. We were taught to turn away from the abundance of our kūpuna (elders and ancestors). We were taught to feel saved by scarcity. We were taught to shame our beautiful brown bodies and the beautiful brown things we did with other beautiful brown bodies in our sovereign beautiful brown dirt.

As more missionaries settled in Hawaiʻi, light and dark were rendered as antithetical. In order to cultivate a better home for the single male Christian god, light and dark were increasingly defined by opposition. In other words, American settler colonialism perverted my ancestors’ sense of dark and consequently corrupted our relationship to light.

So now I’m thumbing through every metaphor I’ve penned for light and dark. Rage and rapture. Asking myself: does this corruption live inside me or do I refuse the inheritance? Is my “no” strong enough, daily enough as a queer femme ʻŌiwi poet?

This was never and will never be an issue of morality; it is a crisis of relation.

I share this with you because I want to read a poem by Haunani-Kay Trask that baffled me as an undergraduate. When I first came across this poem, I was thick in what was then to me a new world of intersectional feminism and Indigenous studies. Remember: an ʻŌiwi woman wrote this.

You Will Be Undarkened

by Haunani-Kay Trask

you will be undarkened

by me led astray

to native waters

sunned until

old mango hills

rise leafless you will come

long and flowing

poured slowly

through the gourd of laughter

spring of weightless

yearning you will swell

at evening’s light

rivers of you

flooded apart and you will

beg me so

in your momentous showing

to keep you translucent

forever

When I first read this poem, I didn’t know what to do with its light and dark. So I read it again. And again. And by the end of the day, I still didn’t know what to do. What do you mean, Haunani—I will be undarkened? I don’t want to be undarkened. I love my dark. I love the brown that made me. What do you mean?

Years later, when I earned her mentorship at the Kamakakūokalani Center for Hawaiian Studies in Honolulu, I got the nerve to ask her about the poem.

“Everyone thinks that poem is about race,” she said. But it isn’t. The poem is about the intimacy of mentorship. It’s not about ripping light and dark from each other. It’s not light winning the war and dark being the vanquished.

Did you even hear the water?

Did I?

Did you?

When Hawaiians ask your name, our word for water appears: “ʻO wai kou inoa?” Who are you? What water do you come from? Haunani’s poem is about returning to our wai (water), to our waiwai (prosperity). “you will come / long and flowing,” she wrote. “you will swell.” “rivers of you / flooded apart.” E ola i ka wai.

So to my fellow poets, my fellow makers of our ancestors’ wildest dreams, I humbly ask you: what do you think Haunani meant when she wrote: “you will be undarkened”? I still don’t have a clear answer myself. I think about it often. So much that I wrote a poem to keep thinking, to bring that line of poetry through my body like a small, hard rock. Because sometimes that’s what writing a poem is—eating rocks of your homeland and being satisfied. Ua lawa mākou i ka pōhaku.

Not today, colonizer. I would rather eat rocks.

The poem I wrote is called “How to Swallow a Colonizer,” which is inspired by Kathleen Lynch and repeats the titular line from Haunani’s poem. Remember: an ʻŌiwi woman wrote this.

How to Swallow a Colonizer

after Kathleen Lynch with lines repeating from Haunani-Kay Trask

1. Brindle your throat.

2. Metabolize the twitching

eyes, tongue, feet.

3. Hold your stomach

with both hands while

his teeth dissolve and recite:

you will be undarkened

you will be undarkened.

This acid, medicine.

4. Always rub your piko.

When the settler breaks down

stick your finger in your mouth

to beckon flowers.

5. Kaulana nā pua.

“Kaulana Nā Pua” is a beloved song of resistance in Hawaiʻi.

Pua, in ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi, means flower.

Sometimes a poem is a rock, and sometimes rocks turn into flowers.

And no matter how many poems I write about aloha, they may still try to kill me.

But I am no one’s graveyard. None of us. Not today, colonizer. I would rather eat rocks.

Oʻahu, Hawaiʻi