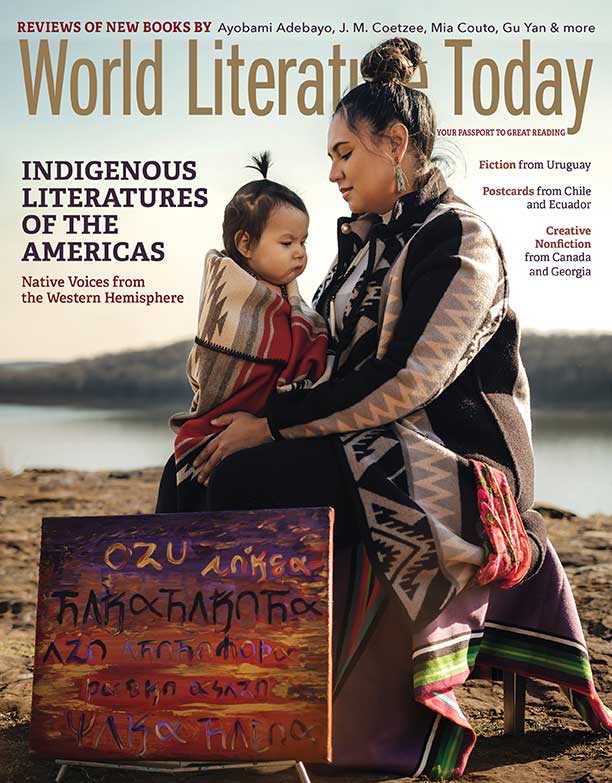

Mother Earth, Womb of Origin, and Language in the Quechua Yanakuna World

Quechua writer and Yanakuna poet Fredy Chikangana explores how the Yanakuna language “contributes seeds to the construction of a world with values and a brotherhood that allow us to safeguard the planet.”

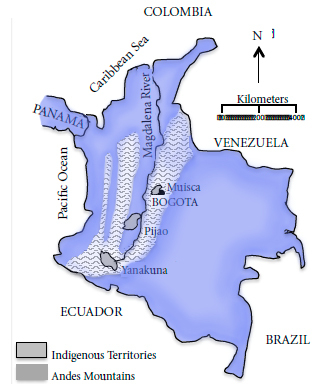

The millennial grandparents of the Quechua Yanakuna universe, in the Colombian massif, have transmitted to us that the original mother is a Tapuku and that her territory is the uterus, in which she germinates life to be watered by the universe. Let’s consider the origin story as it gave rise to the word and the meaning of life from sound:

From the ancient word of the Quechua Yanakuna universe, they say that the first beings who populated this earth came in the form of vapor and were also called Tapukus because they emerged from the bottom of the earth, and when they came to the surface some made the sound of tapuk . . . tapuk . . . tapuk . . . and others responded ku . . . ku . . . ku . . . So they kept jumping and trying to fly. The great father Waira, who was the wind, took them by the hand and took them to his domain, and soon they were turning the earth white, then some tapuk and other ku did not want to follow the great father Waira and gathered together, forming a great shadow, then from that shadow a mass arose, forming an original body that had the sound and the sign of the two, of Tapuk and ku.

Father Waira, feeling rejected, blew hard on this mass, which was taking the shape of a large drop and then took the shape of a woman. Father Waira continued to blow and threw it into the air, but the mass already had a woman’s body. With the force of the wind, the shadow was making the two sounds of tapuk ku, tapuk ku, then the great father, observing that it was a woman, decided to call her Tapuku and accompany her in flight to form with her body the navels of water, the lagoons, the rivers, and the ravines. She was singing, brushing her body in the dark with her sound and breath, the warm and cold waters were forming. The great father Waira blew softly, and thus the waters that began to course through the universe began to well up.

This story allows me to talk a little about the word in a time when humanity is called to witness the transformation of consciousness. There is a reality in relation to our worldviews, our languages and records as original peoples. We say that we are people whose word assembles the first school of life orally, the mandates of Mother Earth, legends, songs and stories of fire, and the sweet word from what we call “the three tulpas of knowledge,” our reality next to Pachamama, (Mother Earth), Mama Yaku (water), the Urkus (mountains), and the spirits. That has been our truth, and even today, even if we walk around the city, we feel that we are a body and at the same time walking territory. We have the memory and knowledge of our oldest grandparents because such knowledge has been handed down from generation to generation through the word. The word and the sounds as elements found the origin of life and the creative mother and father, whom we must thank.

In that flight between “oral tradition” and “writing,” we are people of the water and the wind, we are stars of the universe, we have ancient knowledge, but we have also had to learn to handle different elements that have been taking place in the contemporary world, be it communication or other activities. We also globalize our resistance, our searching, and we remain in the proper place that harmonizes with us in the process of creation and re-creation of life as well as in the preservation of knowledge and transmission of hope for a better world.

We also globalize our resistance, our searching, and we remain in the proper place that harmonizes with us in the process of creation and re-creation of life as well as in the preservation of knowledge and transmission of hope for a better world.

As Quechua Yanakuna people, in my case, I write from orality to generate a “Chaka,” a bridge between what has been transmitted from the word, the way of naming and writing to preserve the memory of our culture, the songs, legends, sounds, languages, and traditions. Our relationship with Mother Earth, with our spirits, with nature, and with water as the source of origin is indissoluble because magic remains in the language and the word that life gave us since the time of our ancestors.

Now, we know that what we call oral tradition started with the first visions that human beings had about the color of Mother Earth and the language of nature, awe at the force of thunder, the roar of the jaguar, the immeasurable flight of the condor, the message of the eagle in the immensity of blue space. Then it was the gesture, the movement of the hands, the lips, the eyes that gave signs of astonishment when witnessing the manifestations of nature, and later came the sign or symbol that would leave the mark on the passage of something along a path or, perhaps, on what was observed in relation to nature. This is how the first signs arose in stone, in wood, in sand.

With the passage of time, beautiful legends, myths, tales, and worldviews were woven where gods and goddesses nest and give meaning to life on earth. This is how the word was configured, from ceremonial songs to pay homage to the divine, to the mystery of night and the stars, or to the splendor of the sun. Then the word arose to name those sounds of the earth, it came from the very voice of the birds, from the same roar of the animals, perhaps from the same cries of anguish in the face of the unknown; only then were thunder and lightning named in this way, only in different languages they were “voice of space,” “voice of the creator being,” and so on. In the Quechua world it was called ILLAPA, which perhaps was meant to decipher that powerful sound of thunder and that glow of light which falls as energy on the earth. It was in this permanent dialogue with the birds, with the animals of the jungle and mountains, with the spirits that the different languages—which give meaning and different interpretations to the human presence in nature—arose.

With the passage of time, beautiful legends, myths, tales, and worldviews were woven where gods and goddesses nest and give meaning to life on earth. This is how the word was configured, from ceremonial songs to pay homage to the divine, to the mystery of night and the stars, or to the splendor of the sun. Then the word arose to name those sounds of the earth, it came from the very voice of the birds, from the same roar of the animals, perhaps from the same cries of anguish in the face of the unknown; only then were thunder and lightning named in this way, only in different languages they were “voice of space,” “voice of the creator being,” and so on. In the Quechua world it was called ILLAPA, which perhaps was meant to decipher that powerful sound of thunder and that glow of light which falls as energy on the earth. It was in this permanent dialogue with the birds, with the animals of the jungle and mountains, with the spirits that the different languages—which give meaning and different interpretations to the human presence in nature—arose.

Many years had to pass so that in the heart of the word, from the languages and from generation to generation, the fullness and the abysses were woven into the heart, the human adventures and misadventures in a filial relationship between earth, humans, animals, spirits. Likewise, so that they could exercise various pictographic forms and also various forms of language and thus be able to understand one another.

From the messages of the smoke, the songs of drums and instruments such as the maguare, the pututo or the shell, the signs on rocks, the fabrics, the traces on the roads, the colored knots called quipus among the Incas, all continued to name the world.

In the story of water’s origin as the uterus of the universe, the sound and the sign are imprinted, the unity with the maternal womb from where the first drop makes its first sounds to condense the word TAPUKU, which becomes the female or male creator from the origin of existence in the Quechua Yanakuna world, a being that feeds on steam and that from the Quechua language names the UKU, which is the underworld, the place from where it ascended to help create life and then ascend to the third world and remain in the clouds and the cosmos.

The word of origin that takes up the sound, as if it were a baby that babbles, that hums, that imitates the bird between smiling and crying until it becomes more formidable each day in naming the present and the absent and then, in the framework of sorrows, in the gloom, in the uprooting, to be able to endure and not lose hope of continuing to transmit dreams of life.

This word was later written with other signs and with a feather crown of medicine by great scholars, but smeared with blood due to the constant invasions, and since the letters are not to blame for anything, they allowed us to describe our greatness and also the pain of our people. With their own or dominated languages, it was possible to narrate and read the deeds of beings made of flesh and blood or beings that emerge from different imaginative worlds and that have also allowed us to endure in the face of new challenges.

Writing is somehow meeting distant or close voices, drinking from sources where the word has been a symbol of resistance through Indigenous languages, but it is also going to other spaces that require our orality and in which other kinds of languages are understood. We write in the native language to remember each moment that we are brothers in chaos, in dreams of building new worlds full of peace and harmony.

We write in the native language to remember each moment that we are brothers in chaos, in dreams of building new worlds full of peace and harmony.

We say that we are in a time of transformation of consciousness, as the Amawtas have called it from our Quechua world, the wise spiritual guides who mention the signs of the flourishing of languages, songs and traditions of the peoples for good treatment together with Mother Earth, the new era of renewal of consciousness in the human heart, the era of love, the era in which Pachamama, the mountain, the river, the jungle are constantly expressing themselves about the order and disorders of humanity.

For these reasons, the original languages and the spoken word from our worldview are in resistance to the different eras of colonialism, but at the same time, it is the word that inquires about the memory of Mother Earth and nature to contribute seeds to the construction of a world with values and a brotherhood that allow us to safeguard the planet.

We must continue walking with the wisdom of the original peoples and seek a closer relationship between human beings, trees, stones, water. You must make an offering to the land to give thanks for life, and you have to continue weaving harmony in circles of community. If we manage to strengthen the first circles of life, we will advance in the universal purpose, that is: to achieve harmony in the family as the first circle, then in the community, and so on until reaching the universal.

It is true that there is no possible perfection, for life itself has chaos embedded in it.

It is true that there is no possible perfection, for life itself has chaos embedded in it, but the word of creation, which names the ruler of the water, the wind, the stars, challenges us to become aware of the search for balance in the human heart to guide life in a better way and return to the womb of essence, to the origin.

I end with a saying from the Quechua language:

ñocanchiska shimi runa ñocanchisca rumi yaku sonkoymanta allpamantawauki cay runa churik causayta

We are human words, we are stone, heart of water, brothers of the earth, we are children for life.

Translation from the Spanish

Read two of Chikangana’s poems from this same issue.