Introduction: Five Younger Women Poets from Azerbaijan

nineteenth-century poet Khurshidbanu Natavan,

Nizami Museum of Literature. Photo: Alison Mandaville

In the center of one square in the capital of Baku, Azerbaijan, stands the obligatory Soviet statue of a woman freeing herself from her veil. This image paints a simplistic picture of gender oppression under Islam–and its elimination under the great modernizing force of the Soviet state. In another square, even more central to the city, stands a statue of the poet and civic leader Khurshidbanu Natavan (1832–97), a woman celebrated both for her lyrical verses and her facilitation of the construction of a critical new municipal water system. Clearly women were busy working and writing—and being appreciated for their work and writing—before the Soviet Union laid claim to the emancipation of Muslim women.

In March 1991, exactly twenty-five years ago, modern Azerbaijan declared independence from the soon-to-be-dissolved Soviet Union. Located in the south Caucasus, about the size of Portugal or the state of Maine, with a population of 9.5 million, Azerbaijan is a place long at the crossroads of the cultural influences of Asia, Europe, and the Middle East. For centuries, Persia and Russia each sought control of the region, and in 1828 the area in which Azerbaijani Turkish was the dominant spoken language was split by treaty between these two empires. Today ethnic Azerbaijanis are Iran’s largest minority; northern Iran is still referred to by Azerbaijanis as “Southern Azerbaijan.” Until a brief period of Ottoman influence in the region, when sixteenth-century poet Fizuli began to write in a form of Azerbaijani (as well as in Persian and Arabic), the region’s literary language was Persian. Embodying this intersection of cultures, today’s Azerbaijani language contains many Persian, Arabic, and Russian loan words, and the influence of Persian and Arabic forms can be seen in Azerbaijani poetry, especially in the oral traditions of Ashiq (poet-bards) and Mugham (lyrical folk music).

During this period, women’s literary production blossomed, supported by educated patrons such as Natavan, who in the nineteenth century held literary salons for both women and men in her home.

By the time of the Russian Revolution in 1905, the capital city of Baku was home to a wide variety of peoples, languages, and religions. A nineteenth-century oil boom had led to the rapid growth in wealth of a group of local families, many of whom participated in movements to reform local institutions of religion, education, and government and to foster the arts. Indeed, by the time Azerbaijan became a Soviet member state in 1920, the push for more education and a larger public role for women was already well established, at least in the bigger towns and cities. In this period, women leaders like Hamida Javanshir, who founded the first co-educational school in Azerbaijan, and the aforementioned Natavan, daughter of the last khan of the Karabagh region, promoted both the education of girls and the cultural and civic participation of women, ensuring that the seeds of gender equity had been sown.

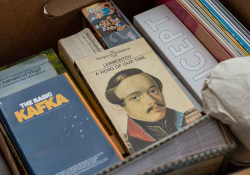

During this period, women’s literary production blossomed, supported by educated patrons such as Natavan, who in the nineteenth century held literary salons for both women and men in her home. This early support for women’s participation in civic and cultural spheres was certainly reinforced by the Soviet philosophy—if not always the practice—of gender equity. Azerbaijanis continue to speak of women as having played a lengthy and central role in the region’s social and cultural spheres. From the same city as the more well-known Nizami Ganjavi, a shadowy twelfth-century female poet called Mehseti Ganjavi, about whom there are few scholarly sources, nevertheless features prominently in Mirza Ibrahimov’s introduction to the first collection of Azerbaijani poetry translated into English (Azerbaijanian Poetry, Moscow, 1969). He praises her and recounts stories (perhaps apocryphal, but no less culturally powerful) of her resistance to traditional limitations on women’s activities more than eight hundred years ago.

While Muslim women, like women worldwide of all backgrounds, may at times struggle for public equity, their lives are anything but homogeneous. The history and daily lives of women from the region of Azerbaijan, mostly Muslim, are far more complex than common Western depictions of oppressed women in scarves suggest. By tradition, women across the Caucasus and central Asia hold positions of significant power in their families and local communities. Nearly half of the country’s wage earners are women; today more women in Azerbaijan graduate from universities than men. The five poets featured here are, indeed, divided on the question of whether women writers face special challenges in Azerbaijan—a sign of increasing opportunities for women.

This is not to say it is easy today for women in Azerbaijan–either in daily life or as a poet. Regardless of whether they hold jobs, women have primary, if not complete, responsibility for the “second shift”–household management, food preparation, and child care. As all over the world, women work hard—at their jobs by day, at home by night. While professional women in Azerbaijan today have more opportunities to meet outside the home than working-class women, spending time in the company of men other than family members—even poets—is still discouraged. Men can comfortably meet together at the many inexpensive neighborhood cafés, yet women are still largely limited to public spaces such as parks or the far more expensive European-style cafés in the center of Baku, where a cup of coffee can equal a day’s salary for a teacher. Neither working-class nor most professional women have the resources to visit these more upscale cafés often. Between the demands of work, family, and finances, it is difficult for women of all classes to find the time for creativity, much less opportunities to meet with other women and develop their own creative communities. When in 2010 we held a two-week workshop for women writers in Baku, many had never laid eyes on each other; one exclaimed during workshop introductions, “Ah! I’ve read your work, but I’ve never met you!”

The prominent writer Afaq Masud, who made the transition as a successful author from the Soviet to the contemporary period, said of women and writing today:

A woman has a multifaceted life—at once a mother, a wife, a daughter, and an office worker. There is a great distance between family life and the life of a writer. It’s like being in an airplane during turbulence—up and down, up and down—nauseating. I have lived my whole life like that—nauseous. Not everyone, especially women, has the ability or occasion to live this way. . . . So, in fact, I don’t advise anybody (I mean girls) to be a writer. It is not a woman’s craft. I think that only the woman who just cannot live without it should become a writer. If I hadn’t been a writer, I would have been destroyed. (WLT, Sept. 2009, 17)

And attitudes about gender are not the only barriers women writers in Azerbaijan face today. The chaos of the decade immediately after the dissolution of the Soviet Union—with its corresponding collapse of the state-supported art and publishing apparatus, political turmoil, a war with neighboring Armenia, and the adoption of an entirely new alphabet—created a literary environment that was, as newspaper editor Rauf Talishinsky has called it, in a coma. The frozen border conflict with Armenia and an atmosphere of fervid nationalism common to newly independent states, fostered by an authoritarian government, continue to channel many public literary efforts toward themes either entirely personal or explicitly patriotic.

By 2007, when we started translating together, the country had stabilized politically, if not as democratically as the West had hoped, and younger writers, whose entire adult life had been lived in a post–Soviet space, began to emerge. Initially, opportunities for publishing, other than paying for the printing of a book oneself, were rare. Quite a few print literary journals have come and gone since 1991—few have staying power, largely because of the time and money required to sustain them. A reading public coping with a mandated nationwide change in alphabet (Cyrillic to Latin) together with the economic stresses of moving from a subsidized to a developing capitalist economy has not helped the already-challenging publishing situation.

The rapid adoption of the Internet in Azerbaijan in the late 2000s, albeit with increasing government regulation, has started to offer more opportunities for publication. That there are still relatively few active creative writers has also made publication in the venues that come and go somewhat “easy,” according to poet Rabiqe Nazim qizi. All the poets featured here have published their poems; several have published more than one book of poetry. Yet despite the increased opportunities for publication in the past decade, many writers in Azerbaijan lament that literature, while a beloved part of their national identity, is no longer taken seriously—even less so, Rabiqe admits, when it is by a woman.

These are not poems that sidestep hard or controversial issues, even as they deal with these issues at times in highly figurative ways: a broken cup, sparrows overcoming a great snowman, one red scarf bringing leaders to their knees.

But being taken less seriously has its advantages in politically constricting cultural spaces. You can fly a little under the radar. While some of these women’s poems explore common and broadly palatable themes of national pride, they also write of domestic violence, rape, divorce, adultery, war, gender inequity, and the strength of female relationships in their lives. These are not poems that sidestep hard or controversial issues, even as they deal with these issues at times in highly figurative ways: a broken cup, sparrows overcoming a great snowman, one red scarf bringing leaders to their knees. Though specific political critique of the government rarely enters these women’s poems, they write in a long tradition of classical and then Soviet-era poetry through which leaders were often critiqued figuratively and obliquely, or through satire. Indeed the concrete nakedness of some of the younger writers’ works does not always sit well with those writers who came of age and achieved literary stature during the Soviet period. Some older writers, such as Masud, argue that the next generation of writers often just writes for shock value and attention (such as there is for a writer). And Rabiqe reports that her parents, who admire traditional formal verse, have a hard time understanding her success with more experimental, free-verse forms. But this conversation itself is a sign of a dynamic literary environment.

The five poets featured here were all born after 1975, and so have lived their entire adult lives since the end of the Soviet Union. They all work at waged jobs, some have children, some are divorced. They are members of, or peripherally connected to, what remains of the official state Writers’ Union, though that body is still largely dominated by men. Some included here have been nominated for or won national literary awards. For the last decade, most have been connected to the larger world on the Internet. Even more importantly, all of these women are now connected through social media, especially Facebook, where they post and comment on each other’s poems. This fast-moving, somewhat ephemeral interface operates, in fact, as a kind of virtual mejlis, or salon, not unlike those that the philanthropist and poet Natavan made possible more than a century earlier. The significance of these women’s relationships with one another in support of their creative work cannot be underestimated in this culture that is still highly homosocial. One poem here by Jale Ismayil, “We Shall Manage,” illustrates the closeness of this group of writers; like many of their other pieces, this one set in conversation with another of the group: Rabiqe.

This small sample of poems was chosen from those offered by the poets specifically for this piece, a kind of post-Soviet self-portrait representing a wide range of subject matters and styles. The selections reflect the diverse ways in which this group of younger women poets has forged, from what was a near coma, an increasingly vibrant, often virtual, literary space for new poetry by women in Azerbaijan today.