Talking to Strangers

After a decade of talking to strangers while traveling, J. R. Patterson explores why strangers make some of the best conversation partners.

Perhaps the worst advice to carry out from childhood, beyond old wives’ tales about giving yourself hairy palms, is “don’t talk to strangers.” Indeed, “stranger danger” is such an embodied part of our culture that, whenever some unfamiliar face holds our glance and asks how we are, we take them for a madman, a thief, or a deviant. It’s a way of thinking that has made a lonely crowd of the world, each of us fearful and suspicious of the Other.

The crooked thing about this fear is that it lives in thin air. A stranger is by definition unknown, yet to be seriously considered a danger, a risk must be known. Anything else is supposition, existing within the malarkey of Donald Rumsfeld’s “unknown unknowns.” As that learned fear of childhood subsides, what moves to take its place is embarrassment; specifically, the embarrassment of being proven a fool by stepping into the unknown—where we ought to know better than to tread.

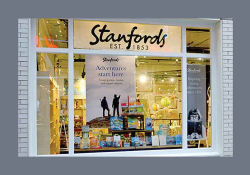

That flight of fancy is what thinker Theodore Zeldin meant when he wrote that “adventure starts in the imagination.” One of Zeldin’s many interesting books, An Intimate History of Humanity, examines the history of our emotions, including fear and embarrassment, through a telescoping look into the past. By thinking long-term, historical past—modern love being an extension of medieval ideas of courtly love, for instance—he surmised that conversation, and nurturing the art of conversation, is the best way to transform our lives in a meaningful way. Retrophiliac that he was, Zeldin believed conversations of the modern day to be boring, becalmed in the doldrums of small talk. The apogee, he thought, were the conversational salons of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century continental Europe, where grand ideas of art, literature, and philosophy were discussed with aplomb.

Almost thirty years on from Zeldin’s proclamation, conversation still seems marooned.

Almost thirty years on from Zeldin’s proclamation, conversation still seems marooned. We willingly compartmentalize ourselves, our social spheres shrunk down to the very basics of communication—afraid in equal parts of being infected by the disease and ideology of others, the people we already know are the only people we meet. The rest are faceless, shrouded behind masks and screens; compelling, perhaps (the mystique of those disembodied staring eyes above the face mask is undeniable), but ultimately negatable. Everyone we don’t want to talk to is simply the voice keeping us on the line, an inconvenience on the road to what we want. But neither do we want to be exposed ourselves. As anyone will tell you, it’s bad form to be too conspicuously curious—much better to leave that to strangers.

It ought not to be that way. Strangers make some of the best conversation partners. With nothing to lose and everything to gain, the stranger can bare their soul and leave whenever they like, feeling the thrill and lightness brought on by their openness. And, perhaps best of all, each encounter with a stranger is like First Contact; one might become good at meeting people, but can never master meeting a person; each first meeting is a one-off event.

With nothing to lose and everything to gain, the stranger can bare their soul and leave whenever they like.

I’ve been talking to strangers for over a decade now, as long as I’ve been traveling. Travel is a condition that requires so much of strangers; it’s their kindness and openness that determine everything for the traveler. New encounters revive us, refresh the mind, and encourage as much introspection as interrogation. It’s the third-degree turned on its head. Instead of questions, you are tortured with answers. “Oh my soul, be prepared for the coming of the Stranger,” goes T. S. Eliot’s The Rock. “Be prepared for him who knows how to ask questions.” What is most surprising is how little questioning is needed: if you let people talk, it’s amazing what they will tell you. I’ve heard from strangers about abortions, divorce, estranged siblings, infidelity, money problems, and hopes for their own death. The more scandalous the better, because the weight of scandal lies heavy, and talking is an act of heavy lifting.

On a recent trip to Vienna, I struck up a conversation with such a stranger. Our tables adjoined, and I had finished browsing the pictures of Die Welt. She was on her way home from receiving a flu vaccination—the circular Band-Aid still on her exposed shoulder. This, despite her step-father having been diagnosed with Covid the day before. She had been on the phone with him, and I could hear the man hacking up a lung from across the table.

“Poor guy,” she said, as she hung up. “I should go visit him.” I told her it probably wasn’t a good idea, what with the risk of infection. “I’m not worried about it. That’s why I didn’t get the vaccine until now. I just don’t feel like I’ll get sick. I don’t feel any connection with illness, so why should I be worried? The body and the mind work together like that. I don’t think I’ll get it, so it will just pass behind me, and I’ll be fine.” She waved behind her back as if dispersing a fart. I asked what her family and friends thought of that. “Yeah, it’s split fifty-fifty. I mostly talk with my friends who also don’t get vaccinated.” She lowered her tone. “But I don’t think I’ll tell them that I got the shot.” They weren’t conspiracy theorists, she assured me, just “concerned about the science.” And apparently not impressed to learn when one of their group folds and gets the jab.

She told me, though, while I sat there smiling like a dog, bemused in her confidence. There was no embarrassment in this woman that I could detect, just a desire to say her piece. Stuck between worlds—a vaccinated anti-vaxxer—who else would listen but a complete stranger? I took it as proof of our default longing to be honest. Around strangers, we can be not only ourselves, but no one at all. Alternatively, one can be anyone, can assume any role. Despite this, most people chose the best, most intricate role of all: themselves. A tall tale might sound engaging, but it lacks the rich background provided only by the truth. It’s the maximum opportunity with the minimum of risk.

Vienna’s strangers weren’t all people muttering aloud about the wax-scene. It was also heartening and fun. In the same way some feelings are better expressed—can only be expressed—in writing, there are things that can’t be said to the people we know and love, who surround us on a daily basis. They require a foreign ear, and no preconceptions on which to hang our foibles and anxieties.

In another café, I struck up a conversation with a young American exchange student. Over the evening, she described her parents, their religiosity, their diet of Fox News, the 35mm snapshots she kept of them—her most treasured item; her recently jettisoned engagement; her desire for control that bordered on obsessive; her growing interest in socialism after learning about Austria’s national health service (not something she relished talking about at home during Fox commercial breaks). All it had taken from me was some gentle prodding and an engaged ear.

Religions have always encouraged talking to strangers: “Be not forgetful to entertain strangers,” the Bible reminds us, “for thereby some have entertained angels unawares.” It’s only officialdom—churches, governments, overbearing parents—that discourages it, their power amplified by the invention of danger where there is none, and diminished by freethinking and self-discovery, both of which conversation dismantles and creates in turn. Bureaucracy is built on power dynamics—even that formless voice keeping you on hold has you by the balls—but the meeting of two complete strangers is a meeting of peers.

Zeldin wrote several books on the art of conversation, speaking to people for whom it is a central need in life. In Conversation, based on the BBC Radio production of the same name, he profiles a woman whose conversational life has dried up; what words passed between her and her teenage son and passive husband amounted to the banal banter between television commercials. Dinner parties are a drag, her friends just a gaggle of egos shouting, “Look at me! Aren’t I great?” She was happier talking to strangers, she says, because “they are more inclined to listen.”

Conversation-as-duet goes back to Socrates, but eavesdrop on most conversations, and you’ll hear tête-à-têtes.

Conversation-as-duet goes back to Socrates, but eavesdrop on most conversations, and you’ll hear tête-à-têtes; two monologues locked in battle, vying for dominance. Anecdotes are thrown like grenades, exploding against the other person, who is made deaf by the priming of their next installment. Perhaps this too is an element of that bygone fear or embarrassment of being passed over, defeated. Strangers bring out a discord of high emotions within us. John Steinbeck, in East of Eden, wrote that Americans were overfriendly yet afraid of strangers. And yet we regret the lost opportunities they represent. The best example of this comes from Walt Whitman’s “To a Stranger,” from Leaves of Grass:

Passing stranger! you do not know how longingly I look upon you,

You must be he I was seeking, or she I was seeking, (it comes to me as of a dream,)

I have somewhere surely lived a life of joy with you,

All is recall’d as we flit by each other, fluid, affectionate, chaste, matured . . .

It’s rather taboo to admit attraction to a stranger now (the insinuation of objectification is too juicy for some to keep from pronouncing damnation), but like all taboos it stems from something older and truer than society, the carnal edge of civilization. Haven’t we all felt the thrill of a stranger’s gaze upon us, the seductive gleam that says, “Come hither”? Is there another look that promises more adventure, more possibility, than those unfamiliar eyes? Whitman continues:

You give me the pleasure of your eyes, face, flesh, as we pass,

you take of my beard, breast, hands, in return,

I am not to speak to you, I am to think of you when I sit

alone or wake at night alone,

I am to wait, I do not doubt I am to meet you again,

I am to see to it that I do not lose you.

Come away with me: the words that belong to the stranger. There’s nothing boring or embarrassing about that. There is fear, perhaps, but not the childish fear of danger. It’s the fear of change, of transformation, of hope. “Don’t be a stranger,” we say to those we want to meet again. After this truth, we may begin to ask new questions with new people.

Gladstone, Manitoba