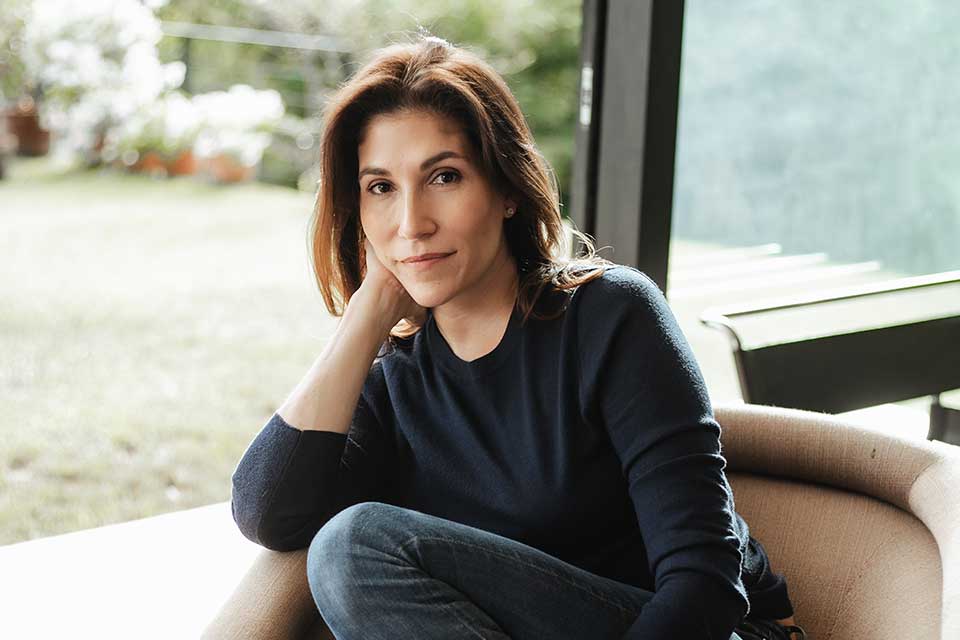

5 Questions for Alexandra Lytton Regalado

Beacon Press published Alexandra Lytton Regalado’s second collection, Relinquenda, winner of the National Poetry Series, in 2022; it was a Featured Fall Book at Poetry.org and was reviewed in the New York Times, Harvard Review Online, and Harriet Books at the Poetry Foundation. Her first collection, Matria (2017), won the Black Lawrence Prize and was listed as one of the Favorite Poetry Collections of 2017 at Literary Hub.

Q

Who are some of the most exciting voices in poetry that you are reading?

A

These days I’ve been rereading the work of Diana Khoi Nguyen. I was transfixed by her Ghost Of; her lyric voice, stripped-down language, and her focus on history, memory, and identity are so powerful, combined with the interplay of altered photographic images. I’ve been lured to read everything related to grief, remembrance, and absence, and her poetry about silences and voids is so on target.

From El Salvador, I have been reading and translating the work of Jorge Galán, Elena Salamanca, Lauri García Dueñas, and Vladimir Amaya. I’m a fan of their work, and I feel they perfectly represent Salvadoran voices of today. Also, I just read Luis Borja’s book UMIT (which means “bone” in Nahua Pipil and focuses on the 1932 massacre of thirty-five thousand Pipil), and I am so moved by his earnest voice, the incantatory use of anaphora, and his beautiful, shattering images. He died in 2019, and it’s a huge loss for the literature of El Salvador.

Q

You have served on the board of directors of the Museum of Art of El Salvador and work as an advocate for Salvadoran artists. Who should we be viewing?

A

There are way too many artists for me to name—I’d give more than a handful of recommendations—but a good place to start is the website of the Museum of Art of El Salvador (www.museumarte.org) and also a literary and arts site that I co-edit called La Piscucha Magazine—where we work to promote the work of artists and writers from El Salvador and those living in the diaspora. The website is bilingual and has links to artists’ websites, too (www.lapiscuchamagazine.com). Issue number two is forthcoming!

But I do want to highlight the work of one artist. The image on the cover of my book Relinquenda is by Salvadoran artist Verónica Vides from her series Mimetizada. She’s been living in Patagonia since 2011, and much of her work focuses on the environment. In her series Mimetizada, human figures are outfitted with costumes made from local flora, and they seem to camouflage with their surroundings; to me, her work speaks to us as immigrants and our need to fit in, our feelings of invisibility, our need for a safe retreat. Her work speaks to me of hermitage, of solitude, and adaptability. She also makes these gorgeous metal sculpture installations in the shapes of mangroves, seeds, insects, and other forms that make me reconsider the idea of home, invasive species, reinvention, and hybridity. You can see more of her work, including her video art, at her website (www.veronicavides.com). Her video series La Barrida of herself and civil war ex-combatants sweeping dirt roads and the plaza of a church in ruins reflects on how difficult, absurd it is to try to “clean up” the events of our country’s history, and how those futile actions actually kick up more dust.

Q

What cultural offerings or trends have recently captured your attention?

A

Well, for some time now I’ve been obsessed with books and shows about survival and wilderness, shipwrecks, mountain climbing, or the experiences of people who live in solitary outposts like lighthouses. I’ve been reading about the history of hermits and recluses. As I said earlier, I’ve been focusing a lot on grief and loss, but I’m also drawn to extreme experiences that bring out our true human essence—focusing on self vs self, and really veering from politics, culture, and other social issues. I play with the idea of taking a silent retreat or maybe one of those mushroom trips in the woods. If in my daily life I don’t have time alone, I am not myself. The title of my book in Latin means “that which we have to abandon, relinquish,” and so I try, daily, to learn to let go, but I’m also fully aware that there are certain elements in this world that we must hold on to as long as we possibly can.

Q

You live in San Salvador. Can you share a few favorite spots?

A

Lake Coatepeque is my favorite place in the whole world. It’s a crater lake, remnant of a supervolcano, and so it’s this perfect blue lagoon in a ring of mountains. There are thermal currents running through certain areas, and there’s an island, a new volcanic cone that’s rising, and here they’ve discovered remains of Mayan ritual sites with statuettes in forms of penislike mushrooms and female effigies. The island is full of ancient trees, birds, and deer. Throughout the decade-long civil war we did not return to the country—I grew up in Miami, moving several times to different neighborhoods in rental houses—and my grandmother’s house at the lake was the one constant, unchanging place that remained of my childhood. My husband proposed to me here, floating on an inner tube midlake, and we were married in the same chapel where my parents were married. I go there and feel recharged. Along the shoreline there are towering ceibas and amates. The light there has a golden quality, and the night sky is a bowl of stars.

Another spectacular place is El Tamarindo in the Gulf of Fonseca. From the peninsula of the beach, you can see the coastal islands of El Salvador and, in the distance, both Nicaragua and Honduras. These are not the perfect surf waves of La Libertad, the famous (infamous?) Bitcoin beach: here the waves are soft and rolling and you can sit hip-deep in the ocean till sunset. The beach has these amazing tidepools with hermit crabs, schools of tiny silverfish, and anemones. These are the two places that are most iconic for me, both spectacular because of their views of water and mountains.

But natural beauty can’t veil the reality of current-day El Salvador. In addition to environmental threats, we are dealing with a lot of other problems. I can’t get into it, but you can investigate reports from El Faro and other nongovernmental news sources like El Diario de Hoy to understand more about what’s going on. We are currently in the seventh consecutive month of the State of Exception, which suspends our constitutional rights, including free speech.

Q

I saw poet Christopher Soto tweeting in August that five Salvadoran writers just released or will soon release books and that this feels like a moment in Salvadoran American literature. Can you expand on this?

A

Salvadorans are the second-largest population of Latinx immigrants in the United States. I’m happy our voices are being heard. In addition to Christopher’s first full-length collection, 2022 and 2023 bring us poetry by Yvette Siegert, Cynthia Guardado, Claudia Castro Luna and fiction by Alejandro Varela and Reyes Ramirez; in nonfiction there’s Raquel Gutiérrez and Roberto Lovato, and of course, Javier Zamora’s stunning memoir.

Something that’s important to note is that not all of us are writing about the civil war; not all of us are writing about violence and immigration. There is a tendency to want to pigeonhole our works into those topics. I don’t know why—it follows the Salvadoran stereotype, what’s considered a sexy or expected topic, I guess. But there is more to us than our trauma and nostalgia. I am also interested in the everydayness of Salvadoran lives. My poetry doesn’t talk about the war per se, but everything I write carries an undercurrent of anxiety and questioning. In the end, everything we write will be Salvadoran because we are Salvadoran. We do not need to include pupusas, torogoces, and mangos or directly reference the armed conflict. For some of us, it is part of our origin story—we were born in the US or grew up there because of the war, but it isn’t always the touchstone of our work.

Regarding contemporary Salvi writers, the list is huge, and I urge everyone to look out for us. Que orgullo salvadoreño, there are so many teachers, academics, filmmakers, chefs, artists, athletes—a Salvadoran woman recently summited Everest. ¡Estamos por todos lados!

Alexandra Lytton Regalado is a poet, editor, and translator with a black belt in Kenpo karate. Her poems, stories, and nonfiction have been published widely.