Two Latinx Poems

Landscape at the Third Stage of Grief

by Alexandra Lytton Regalado

I

This year my knees are having a hard kneel. This candle’s fire

has two hard eyes. The tree outside my window is two

hard branches. My ankles cross at their hardest.

Mornings crack open a blade. Words stagger, snag

on the hem of curtains. The sprinklers always turn on

when I want to lay on the lawn. The lawn has a bad burn.

Our dog knows to lay out in the sun for twenty minutes.

Our bones are depleted and hungry for sun. But the sun

has moved slant. The rains, too early. Flowers will fall as buds.

My mother will never see this tree in bloom. It has been a hard year

for a daughter. I am now the matriarch. It’s a hard year for matriarchs.

There is no April in these bones. There is a craving for salt,

new imagery. It’s all about leaves, cut leaves, dry leaves. No more

talk of things that grow. Perhaps, consider the roots,

the ground they push against. It’s been a hard year for mothers.

Why does it surprise us when things are hard? Death leaves us

untethered. What grows without roots? What is the thing my mother

said in the unlit room, sitting at the foot of my bed, when I could smell

her perfume, and her deep voice and I sat up and asked,

Are you there, and woke up? I could smell sandalwood and see

her knobbed hands. Now, she looks at me from a distance.

Is she now birdsong, is she the knot in my stomach, the thing

I search for as I enter every room. It’s been a hard year

for me. There are no metaphors in that statement. No twists

or ribbons of glitter trails, just the stripped, plain dirt of it.

The ripped-out root, the hole in the ground. The things that

no longer bloom. The water I continue to pour into the ground.

II

Birds throw out their song and do not care

that the grass is scorched, and they tease out insects

from the blades or shift midflight to catch them

in the air. I am the one that is hard. I am the one that is chipping

away. I am the stone that meets the spade. I am the one

that tumbles and turns her back. I am the pumice to leave

everything smooth. Rain over me. Slide over me. I want it all

to pass. I am brown and dry, the mountainside crying its alarm

of cicadas. The tree made better because it adapts,

the tree with a fallen branch, torn by wind. It’s been a hard

year for all of us. And we are two stones clicking together.

We will never be in stasis. I dig and dig and my hands

elbow-deep and the rocks never end, this ground not apt

for plowing; plants move around stones and I am

the stone and the root that wraps around the stone.

Patria Archipelago

by Leo Boix & Alexandra Lytton Regalado

responding to Kati Horna’s photographic series Ode to Necrophilia

And then the time came to be inside

And then the time came to be inside

this island a room he carved out of

(the mask

grinned, the mask always

grinned)

foreign things he often dreams of: an English

umbrella by his unmade bed

a pair of worn-out shoes (not his) a candle—una vela candela

burning in broad daylight

Outside, a desperate fire . . .

He stands half-dressed in the middle

of the locked room alone, marooned

His face in his hands—

el rostro en sus manos unmasked

* * *

Yo te velaba,

I am the lit candle at your feet,

already mourning you,

y tu también me velabas.

All that happened before

does not matter, now, in this room,

as years pour over us, the sun sharpens

the walls, our outlines lit

in this cleaving.

* * *

He leaves the mask on his pillow

a catafalque then the mask speaks:

“Beneath the black veil an orphan

wanders the whitened fields of Argentina”

Time stands still the candle stops quivering Father returns

to ask hijo, are you alright? Back then I didn’t want to know

his husky voice

disguised . . .

He brings a mirror from the afterlife hijo, mirá

hay luz del otro lado

del túnel

The mask reveals a face bone-white shell, lunar

empty carapace, a husk

alabaster, a shard.

* * *

* * *

Your hands, which I loved,

now a clutch of twigs, paper skin,

galaxies of bruises.

Bedside, I pray a rosary

you would believe in

counting no beads, but fingernails,

evidence of our survival, mouthing words,

rubbing the pads of my fingertips,

smooth as polished stones,

and your breath the ocean

raking over those stones.

* * *

He crossed the ocean on a ship of fools

inside the vessel a memory of

what he’d left behind he traveled at night

held a candle on his wooden cabin, a single bed

he dreamt of rundown ports quays a murky river

the intense heat of the subtropics a desolate wake

filled with carnivorous flowers from far away

the mask spoke again:

look down at your own past

his hands clasped

in a cup—un amuleto

smeared with mother’s betún

for an auspicious journey.

* * *

Sunlight and smoke coax things into visibility.

You, at a distance, in a landscape I invented—

and how that distance rendered us perfect,

the dividing contour of the body no longer there.

I thought it my job to find the plot,

to create a list of things good and bad

that could happen.

But the story was in the telling,

the details we chose to include.

The moment I decided a castaway’s raft was a better fate,

as a bird flings itself into empty space,

because the story can’t end when the pain begins.

* * *

* * *

Él, dentro de la casa que no era

en ese continuo

deshacerse

underneath the rugs

behind the commode

by the heavy wardrobe

there are books in Spanish

que no volverá a leer

golden spiders, trilobites

house martins without southern magnets

there is a photo

de cuando se despidieron en el aeropuerto. . .

a distant airport

days ancient days

when nothing much happened

todo se va deshaciendo . . .

Mask speaks to him:

“Build a nest

inside a hollow tree

in the form of your father’s body

It’ll take you a lifetime to complete it”

* * *

At home, you were the ghost

that haunted the doorway,

a hunched figure in the corner

of the living room, hooded

and blending in with the furniture.

You had to live in another

continent to feel our distance.

Letters from a Buenos Aires apartment

on Avenida Libertador,

it was the most you’d ever written to me.

I am still the reader of these pages, hunched over them,

always, even when I look up.

Mornings I’d find a spool of pages;

how my fingerprints

on the slick paper erased your words.

I burned those words

into my skull: bruising

purple and orange solar flares.

A cave to revisit, to study your words

like glyphs of hunted animals.

From the thin air launches a quiver

of arrows and meanings engulf me

sharp as rain.

* * *

His father’s lying body

lifted to a fourth floor

a badly oiled elevator

a place smelling of decaying

flowers, diluted

bleach.

Inside a chapel, a large cross made of flickering

neon violet lights

a small woman washing slabbed floors

lost bees

trapped inside

The son wasn’t there they told him on the phone

He remembers the light those big tropical orchids

in the shape of multicolored

cut-out hearts

their aerial roots going down

In the dream, his father sings

behind heavy curtains

in the southern house:

“Lo que queremos decir y no podemos /

lo cubrimos con un manto azul y transparente”

* * *

We are the music of smoke, of red wine, of racing hooves,

of leather, of dust, of slanting sunlight.

At your bedside worrying my cuticles, biting off

frayed bits of skin,

my back to the door, light slices

through the wooden slats onto the white sheet.

I lean

to whisper in your ear, words

etched in the cave.

You furrow your brow, a fraying dream;

I smooth the wrinkle

with my thumbs.

Your body now a skein, telling us clearly now

what we are: bones.

My left hand itches and I wonder what it is

they say: will I lose

something or find something?

Will it be harp strings and no more

breath, one more breath, a gasp,

like the cough which could have been a laugh, a cry

urging a horse to gallop.

* * *

Outside his room the world he knew was beginning

to vanish everything changed the orphaned

world of the past the island within the mask wasn’t there anymore

father had sent a last message un último mensaje

in a green bottle a bottle perfectly beautiful

the inside of a whale its crystal membranes of the past to be delivered

to his only son el hijo del medio it arrived safely

the bottle carried an infinite letter

a bag with

his shining fluorescent bones

birthmarks ossuaries to remember

like grieving pachyderms on an aimless trail his last words

inside the glowing glass

“Querido Leo

Let this be our story”

* * *

Because I will do as the wind instructs,

traveling like Theseus’ ship,

every nail, every board replaced

as it traverses oceans.

Each decade our cells renew;

is it the same ship,

are we the same

father and daughter?

We mistake our ideas of things for the things themselves.

I pose for the memory in your eyes,

but, as always, it is when I step away

that you reach out.

I will stand in the patio and watch your deathbed

through the window

as the clouds part, no moon summoned by tides,

not Venus Nixtamalero,

but a single nameless star, and you will disappear

from this known world

the way a pebble ripples into still water.

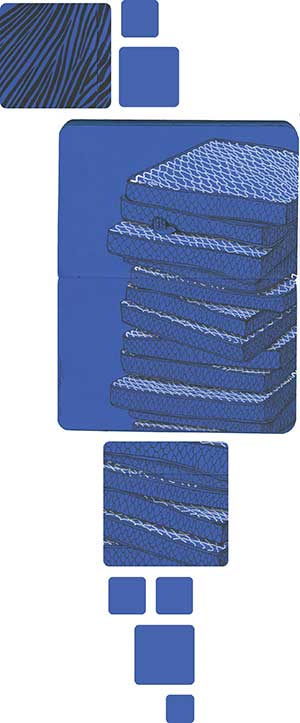

Editorial note: Read a conversation with Lytton Regalado. This long poem was made into a short film, animated by Salvadoran artist Ulises Vaquerano Ramírez and produced by Nuevo Sol, that premiered last October at the London Literature Festival at the Southbank Centre. The illustrations included here are from Vaquerano’s work animating the film.

Ulises Vaquerano Ramírez is a Salvadoran visual artist and art director, who deals with themes of memory, interiority, chaos, palimpsests, gender, queerness, and migration, as they have experienced since their residence in Mexico.