Besa

Going back to the medieval period, the word besa is a small word with large implications throughout Albanian society, from law to literature to history. And in a world that sometimes seems to be tearing itself apart, it may be the small word that meets our current challenges.

Learning a language, therefore, is not only learning the alphabet, the letter sounds and the shapes, the meaning, the grammar rules, and the structure or arrangement of words, but it is also learning the behavior of the society and its cultural customs.—Kadri Krasniqi

Can a word be the glue that holds a cultural community together? Can two simple syllables extend tendrils throughout a diverse state and connect at levels from empire all the way down to the everyday? And if so, would it then be possible to uproot that word and plant it into another language?

The Albanian word besa goes back to the medieval period, and its origins as a social concept may go back much further. It has played a central role in some of Albania’s most significant literature and mythic narratives. It has even been a part of world-historical events that have played out on Albanian soil. All in all, it is a concept that touches the lives of many daily.

Besa—literally “to keep the promise”—means, in the words of scholar Kadri Krasniqi, “taking care of those in need, protecting them, and being hospitable to every single human being you have given your promise.” The word is interwoven into the very meaning of Albanian community, as seen through scholar Besmir Shishko, who writes that “besa contains mores toward obligations to the family and a friend, the demand to have internal commitment, loyalty, and solidarity when conducting oneself with others.”

Sources tend to agree that besa came about in part because of the frequent incursions of invaders into Albania’s territory throughout history—when anyone could be turned into a refugee at a moment’s notice, community norms toward hospitality, protection, and solidarity would make a lot of sense. As a legal doctrine, besa goes back perhaps to the fourteenth century, when the Statutes of Scutari, a legal code for the region (which was then known as Scutari), documented the concept of an oath as a part of the social order. Since that time, besa has been passed down for generations as part of Albania’s Kanun, a set of common laws that has governed the lands since the fifteenth century. Beyond the legal sphere, some see the very idea of besa as possibly originating in the Christian Bible, while others, such as leading Albanian author Ismail Kadare, consider it as predating Christianity. With the opening of Albanian society and overall modernization throughout the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, the concept has begun to lose much of the cultural currency it once had.

Besa has been passed down for generations as part of Albania’s Kanun, a set of common laws that has governed the lands since the fifteenth century.

A notable act of besa that reappears again and again in the literature surrounding the word occurred when the Albanian population protected thousands of Jewish individuals during the Holocaust, taking them into their very own homes and treating them like family. This act is perhaps even more remarkable when one learns that, at the time, Albania was the only nation in Europe where the majority of the population was Muslim. This diverse country considered it its besa to protect Jews by granting them false identity papers and hiding them within their homes. It is a point of cultural pride that, according to many accounts, the refusal to aid and abet the Nazis was so thorough that not a single Jewish person was turned over to Nazis by Albanians during World War II, despite intense pressure by the occupying forces to give up lists of Jewish people.

Decades later, during the wars of separation that occurred as the former Yugoslavia splintered into individual nations after the fall of communism, Albanians again showed care and hospitality to those caught up in horrific, genocidal acts. Writer Hamza Karčić recalled his experience of besa as he fled Slobodan Milošević’s siege of Sarajevo as a ten-year-old boy:

In my case, long before I had ever heard of the concept of besa, my family and I experienced it. Other Bosniak families who came to Macedonia with us, as well as many who poured into the town in the following weeks, were similarly given besa by other Albanian families. . . .

Albanians’ besa to Bosniaks was not a top-down decision. It was a grassroots, people-to-people, humane response to an ongoing genocide. Nor was it the only time Albanians had acted this way in the twentieth century. It is a testament to the power of an informal code of conduct and a reminder that acts of immense faith and hope do take place.

Beyond wars, the concept has also figured significantly into Albanian history via politics. In one major example, the concept was integral to Albania becoming an independent nation from the Ottoman Empire; as Bedri Muhadri explained in an article in Kosovo Online, “by forming the League of Prizren in 1878, besa was given to fight for the independence of Albania against Ottoman rule.” Muhadri also explained that besa has factored as a way for politicians to build consensus among the population for major policy proposals. “When the unity of the Albanian masses was sought to achieve their legal and political rights, they gave their word and thus, through faith, created lasting trust and cohesion.”

Beyond wars, the concept of besa has also figured significantly in Albanian history via politics.

One of the earliest instances of the concept of besa in Albanian literature is found in the age-old ballad “Constantin’s Besa,” which tells the story of Constantin, the youngest of twelve brothers to only-daughter Doruntine. Constantin promises his mother to bring back Doruntine after she is married far from home, and even dying in a war does not prevent Constantin from keeping his besa to his mother. Constantin does, in fact, bring her back home, and in the climactic finale, both women realize the Constantin has risen from the dead on his sister’s behalf.

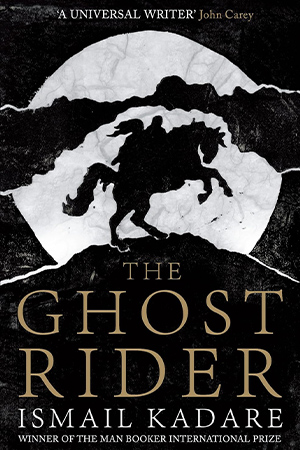

This ballad, which is often sung at Albanian weddings, has been the subject of much literature, notably Kadare’s novel Kush e solli Doruntinën? (literally, Who brought Doruntine back?, although translated into English by Jon Rothschild as The Ghost Rider). Kadare adds his own flourish to the legend by placing it in the context of a medieval police procedural and adding the character of the detective Stres, who must solve the mystery of how the dead Constantin could bring back his sister. In Kadare’s hands, the story turns into a meditation on the birth of legend, the origins of Albania’s version of Christianity, and the source of its Kanun laws.

This ballad, which is often sung at Albanian weddings, has been the subject of much literature, notably Kadare’s novel Kush e solli Doruntinën? (literally, Who brought Doruntine back?, although translated into English by Jon Rothschild as The Ghost Rider). Kadare adds his own flourish to the legend by placing it in the context of a medieval police procedural and adding the character of the detective Stres, who must solve the mystery of how the dead Constantin could bring back his sister. In Kadare’s hands, the story turns into a meditation on the birth of legend, the origins of Albania’s version of Christianity, and the source of its Kanun laws.

More recently, the legend of Constantin and Doruntine was transformed into a bilingual children’s book, Doruntina’s Besa, released on International Women’s Day in 2021 by the United Nations. Notably, the book aspires to feminist goals by giving the legend’s besa to Doruntine (who is the hero of this book) instead of Constantin. In the words of the book’s press release, “This publication aims to teach children, youngsters and adults alike, that boys and girls bring the same happiness into families’ lives and that no one should have the right to decide for women’s and girls’ marriage.” It is an example of how the concept continues to have cultural currency, centuries after it was first codified into existence.

Scholars Craig T. Palmer and Amber L. have argue that literary texts have played an essential role in transmitting besa through the centuries. They believe that literature has been a significant part of ensuring that the concept has retained cultural value:

The behaviors prescribed in the Kanun were not simply transmitted from parents to offspring as simple instructions of how to behave. Instead, the tradition was made more interesting, and thus more influential, through being transmitted in stories, songs, and plays, and these accompanying behaviors often emphasized the importance of keeping one’s besa to sacrifice for others as prescribed by the Kanun. Whitaker (1968) explained how “traditional Albanian epic songs (këngë trimnijë) . . . reveal the Canon of Lekë Dukagnini in operation,” and Mustafa, Young, Galaty and Lee (2013) observed that the pledge of besa to follow the social behavior required by the Kanun is “informed by cultural narratives so immense and unique to the people of the valley that entire books have been written about them.”

Translation of besa is quite challenging, not least because it is so fluid and shifting a notion.

If Palmer and Palmer’s argument is true, then the translation of literature that centers besa in foreign languages may play a substantial role in spreading this concept worldwide. But translation of besa is quite challenging, not least because it is so fluid and shifting a notion. In the words of writer and translator Tom Phillips, “It is a quality, an obligation, a gift, but it can also mean truce, haven, protection, peace. It is none of these alone, and all of them at once, existing where they overlap or, like mortar in a wall, in the gaps between them. . . . Nor is besa a necessarily fixed concept: its definition is open to negotiation on, as it were, a case-by-case basis.”

In a world that is often critiqued for being overly transactional, based more on economic relationships than relationships based in human mores of community and connection, and also a world that at times seems to be tearing itself apart, besa would seem to have much to offer. Perhaps the very things that lead Phillips to say that besa eludes translation—that is, its flexibility and multiple nature—are those that make it so pertinent for the challenges that we face today.

Oakland, California