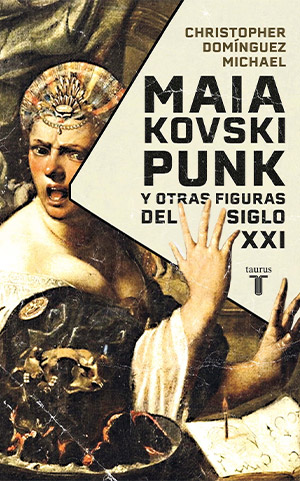

Maiakovski punk y otras figuras del siglo XXI by Christopher Domínguez Michael

Mexico City. Penguin Random House. 2022. 647 pages.

Mexico City. Penguin Random House. 2022. 647 pages.

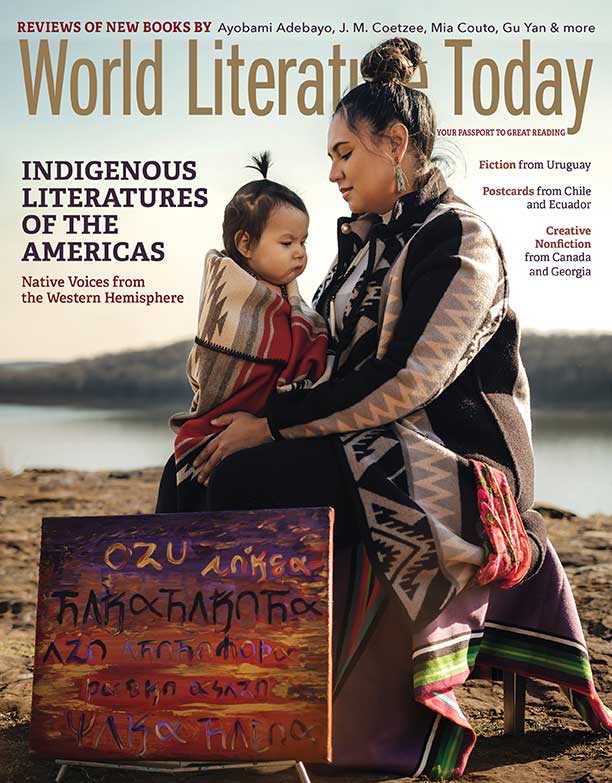

Bursting with intelligence and information, this compilation by the prolific cultural critic and intellectual Christopher Domínguez Michael is a vade mecum for world literature, broadly understood. That it is written in Spanish is a reminder that “angloglobalism” is inherently misguided in ignoring or underestimating reading that literature in other languages, as Domínguez Michael asserts in his analysis of Minae Mizumura’s The Fall of Language in the Age of English (2008) or Paul Veyne’s Palmyre. L’irremplaçable trésor (2015). Easily parsing cultural connections in various Western languages, exhaustively informed, heeding the honesty and avoiding the “anemic vocabulary” of criticism that Richard Gilman enjoins in “The Necessity for Destructive Criticism” (1961), this heir to Octavio Paz, his mentor, proves the need to read critical voices in other languages.

Self-taught, a nonacademic francophile and anglophile immensely knowledgeable about history, philology, and cultural studies, Domínguez Michael’s articles, essays, and extended book reviews probe literary and cultural phenomena of the last quarter century. Expanding by about a third Ateos, esnobs y otras ruinas (2020), the first edition, he readdresses the recent Western canon, spurning Pierre Bourdieu’s “hazy sociology,” questioning the assets of cultural capital (especially in committed writers), and tweaking the worldwide “republic of letters” in his respectful obituary of Pascale Casanova. Forthright without turning disagreements into boxing matches, Maiakovski punk y otras figuras del siglo XXI’s four parts examine “Invocaciones,” “Maîtres à penser, todavía,” “Lenguas vivas y lenguas muertas de América Latina,” and “Novedades antiguas,” mindful of the need for a new cartography of Western cultures.

The most controversial and challenging part is the second, in which he teaches more than a few lessons on Žižek, Foucault, Heidegger, Kundera, and Said; preferring ideas embedded in writings by Fumaroli, Vargas Llosa, John Gray, Garton Ash, Michiko Kakutani, and “the nonagenarian Argentine philosopher” Oscar del Barco. The figures with whom he sympathizes refuse the call of the tribe, even now when just about any idea, or critic, can be hastily canceled, criticized, or censured. Thus, the most representative essay in this part is “Intelectuales, los franceses,” focused on Bernard-Henri Lévy and Houellebecq, Badiou, and Finkielkraut, and comparing the Frenchmen’s lively sparring to the “tiresome” exchanges between Coetzee and Auster.

His resistance to such a state of affairs prevails in the third section, centered on Latin American figures, critics included. If he privileges Southern Cone writings, the justification may be that he publishes abundantly about his native Mexico, frequently exhibiting social conservatism. Enthusiastic about the Argentine novelists María Moreno, Mariana Enríquez, María Gainza, and the great critic Beatriz Sarlo as well as the Cuban novelist Wendy Guerra, he is very critical of writers like Ricardo Piglia, whose artistic contradictions are those of “an annoyed leftist,” to which others add a “clichéd critic.” He is sterner in pointing out the ethical failures of the Mexican “Crack” group (and their godfather, Carlos Fuentes), made up of writers who came of age in the 1990s, although objective about some of their successes. Rightly, he is kinder and actually admiring of the late Mexican novelist Daniel Sada and the Argentine César Aira.

The first part invokes a variety of French, English, Spanish, eastern European (some exiled in Mexico), and Latin American figures, losing some of its democratic emphasis when he recriminates the past sins of progressives (Sartre, Walter Benjamin, the Uruguayan Mario Benedetti), at the same time being quick to forgive the ones who have repented. Leszek Kołakowski, Robert Lowell, Artaud, Ortega y Gasset, Pedro Henríquez Ureña (the first Latin American to deliver the Charles Eliot Norton lectures), Pound, Camus, an inflated Harold Bloom, the brilliant Mexican journalist Carlos Monsiváis, and George Steiner are cause for joy for Domínguez Michael. If the question is how to mix that cocktail, the best way to proceed is to carefully measure its ingredients.

The final part, “Novedades antiguas” (antique novelties), is a tour de force for this interpreter of world literature whose literary elucidation is persistently complemented by accentuating sociohistorical contexts. Thus, “Estado de peste: abril de 2020” and “Estado de Guerra: marzo de 2022” are timely, stark reminders of the literary ramblings round the Covid-19 pandemic and the Ukraine crisis. Maiakovski Punk y otras figuras del siglo XXI bursts with insight because of its author’s humanistic core and the anxiety and joy that permeate his experiences. This is evident in his reading of South Korean critic and philosopher Byung-Chul Han and Gainza (an art critic before becoming a successful novelist). Why is Mayakovsky “punked” in the opening piece of this part? Because the Spanish novelist Juan Bonilla’s Prohibido entrar sin pantalones rewrites that poet’s life emphasizing why, not how, one is taken in by antiheroic figures, another foundational question for Domínguez Michael.

In interpreting old and new world literature, he and his only peer in range and fearlessness, the equally prominent Spanish critic Ignacio Echevarría (in El nivel alcanzado: Notas sobre libros y autores extranjeros, 2021), are unmatched, and the current status of academic commentary proves them right. Examining global English in Professing Criticism (2022), John Guillory avers that “global Anglophone is a force that does not answer simply to the demands of the West, much less to the imperial authority of Britain or America,” stressing that the resulting contradictions assume that “teaching world Anglophone is more politically progressive than the transmission of the national or imperial—or let us say, ‘traditional’—canon.” Domínguez Michael substantiates that point, and much more.

Will H. Corral

San Francisco