What's in the Notes: The Sound of Jazz in Poetry

Listening suggestion: While reading Camp's essay, listen to Louis Armstrong’s version of the Fats Waller song “Black and Blue," available for streaming on YouTube.

Can a writer ever hope to successfully render an aural form in words? Can that writer make it possible for us to appreciate what we might otherwise hear? To complicate the chance of adequately capturing sound, try asking that writer to express jazz—one of the most sophisticated musical forms, a construction that demands a certain openness and perhaps even experience with the music.

Some writers are able to turn jazz inside out, making us want to listen more closely. Each writer sees different seams, different ways the music is stitched together. Each is courageous because, after all, jazz is crazy-impossible to style even the first time, and these writers are re-styling it for us.

In my years broadcasting jazz on the radio, the most common comment I've heard is a simple one: "I just don't understand it." Jazz is a remarkable beast—a many-headed animal, one many people seem afraid to get near. How can we define jazz? Is it Miles Davis's Bitches Brew and the fusion sounds of the 1970s? Is it the ethereal and abstract structures that today's musicians keep building? Is it something else? We may need reassurance that we can get close, that we can let the creature climb into our lap.

Certainly, if you come to jazz with a knowledge of music and how it is created—in other words, if you are a musician—you know about seconds and fifths and scales. You know about melody and time signatures. You are already educated about how to decipher phrasing and multitextural sounds.

If you come to jazz as a historian, the music repeats what you already know. Jazz, in particular, is a vital chronicle of where we are, or where we just were. In more than one sense, it is a "record" of the times. Musicians figure out a way to corral politics and their own personal wounds. Then, through their instrument and ensemble, through their compositions and concerts, they give voice and expression to what is happening. Poets do the same, shifting words, meaning, and metaphor to build a rhythm and harmony, to build a statement.

But what happens when a writer takes the audible input away, when words—and more specifically, poems—become the only sounds we hear? This could confound a reader—or maybe, if we're lucky, clarify.

Just as with poetry, you can come to jazz with nothing, no understanding. Perhaps this is the best way to appreciate any form of expression. As a visual artist (among other all-consuming disciplines), I am most moved by the response of people who react viscerally to my work, then disavow their comments because they have no formal art education. To know nothing might just be the truest way to experience any complex art form. You respond with your body and your feelings—and leave the analytical, thinking mind to the side. All it really takes is the ability to open your senses and receive.

***

You might wonder why jazz is so inspirational to poets. Poetry and jazz have long slept together; the Beats merged the two into an uncensored, often stream-of-consciousness style that seemed to fall as easily from their pens as Dizzy's and Bird's notes fell from their horns. Sounds spewed and streamed; they rushed out in all directions.

But that is not the only form jazz poetry takes, nor should it be. The canon of jazz is enormous; it allows for many different styles of expression. The giddy notes of "traditional jazz" date back more than one hundred years. Those sounds eventually led into the busy maze of bebop. No matter how that music twisted and turned, it still provided a wonderful network of possibility for sound. The music was easy to get lost in, and if you didn't emerge again for a while, that was okay too. It took you somewhere, as all good art does. The music flowed from and through that complex wall of sound, and from the postwar dissent of those times. It is astounding to hear how much a musician could manage to say before the vinyl ran out.

The music didn't stay there, though. Jazz kept swinging forward, shifting and reflecting the ever-evolving structure of our society. Today's jazz is a sound that is impossible to describe in one way. It is urban noise pressed against the edge of hip-hop, and it is sound that travels down wide avenues of patience. It is sound that branches out and up until you are not sure which tree you've climbed or why, but meanwhile, as long as you're up there, you might as well admire the view. It is sound that allows us to forget the grief and ceremony of the world around us, or sound that pushes us directly into what might seem like darkness and disorder. It is frivolous and it is necessary.

If you happen to be moved by the music—and you also happen to be a writer—it is natural to attempt to define this malleable, miraculous substance, to hope to gather it in your hands and make sense of it in your words.

* * *

One of the truly bright spots in jazz is each proclamation of something that came before—the hint of a previous tune, quoted, then turned on its head. When you hear a familiar sound reconstructed from an earlier generation, it is like being given the currency to buy your way into a new tune. And isn't this, in a way, what our authors are doing—spinning jazz so we might almost understand, if not the whole of it, at least one perspective? The poet has lived with the contents of that tune, that musician, that music. It is in him—and from it, and from what he finds nearby in his world, he presents it to us. So the music continues in these words, accompanied by the author's response to the chords and notes, the news he hears and the hurts he feels.

We can't talk about jazz without considering improvisation. Jazz is built on the unexpected. It is improvisation that gives jazz its achievement, and even more so, its electricity. Put three or four musicians in a recording studio or on a stage and see what happens. Then, put each of them in new configurations with other musicians. A tune you've come to know becomes something entirely unexpected when launched in a different setting. For example, bassist Paul Chambers showed up on such seminal albums as Lee Morgan's The Cooker and Thelonious Monk's Brilliant Corners. His playing remained constant, but the ensembles are different, and the compositions even more so. Chambers's bass steadies and fuels each group forward, using every opportunity to help them pattern a unique sound.

The poets in this special section pull us into the music in various ways, sometimes pointing us toward the center, sometimes walking us around the outside. If, at times, we hardly notice that music is taking place, we are instead accessing something equally valid—where the sound has taken that writer—in other words, why the music exists for him.

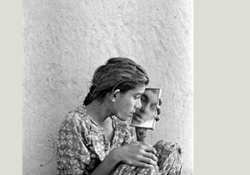

In the highly imagistic poem by Virgil Suárez, "Latin Jazz on the Go in Havana," the reader gets a sense of the squalor from which music might emerge. Is it this poverty of surrounding that gives rise to such luscious, heated music, or does Cuban music evolve spontaneously despite these hardships? Could it be the antidote? Who knows, but Suárez gives us a new way to hear. Using rich language, he tells us clearly what makes up the backbeat of the music that allows our hips to move so effortlessly.

Listen to Louis Armstrong's version of the Fats Waller song "Black and Blue," one of my favorite vocal renditions of any song, ever. Once we expose the full title, "(What Did I Do to Be So) Black and Blue?" we begin to understand Satchmo's very poignant way of reporting on racially divided times. Jazz distills a story to its essence—then serves it up in a palatable way. Poetry, also, finds unexpected ways to say what needs to be said.

Ghanaian writer and social commentator Nii Parkes writes, "it's OK when the needle hits / the dark flesh of wax and causes blue screams . . . the note can't leave the music, like / the shadows can't leave the darkness." Rather than turn away from issues, jazz and poetry address them. As listeners and readers, we need that determination to see, react to and explain what is sometimes too hard or too strange to bear any other way.

We also introduce you, in these pages, to German-born, U.S.-based Adrian Matejka. He's describing the music of Esbjörn Svensson Trio or EST, Sweden's famous jazz trio, which can now only be heard in albums since its leader died in a scuba diving accident. The poem explores the "cantilevered / moment of swell & letdown." And this is what music is, why disciples go to concert after concert. The music doesn't stay with us; it fills us, then escapes again, and we need a recharge. As I read Matejka's poem, I am reminded that jazz couldn't exist without the instruments, which are themselves works of art, objects with a past.

* * *

I can't help but cheer for anyone expanding on jazz, when the future of the genre is in ongoing peril. Music venues keep closing, and radio stations revamp their programming to more profitable forms. For those of us who adore the music, we are obligated to share it. Otherwise, how will it survive?

Sound is miraculous—a tap, or exhalation of air, the movement of a finger to press a key. Just that, and vibration results. With training and skill, that vibration turns into something fuller, something marvelous. For me, the collection of poems that follows roars with possible ways to open your ears, to tune your mind to music you either already accept, or feel you couldn't possibly understand.

In this world of greater and greater connection, connecting jazz and poetry from the perspective of the larger world makes sense. In Romanian writer Virgil Mihaiu's epic catalog poem, the litany of names, and the associations he makes, might not be entirely familiar, but it tells you immediately of the long history of jazz, the many notes you may yet explore. If jazz distills a story for us, these poems continue that story, picking it up from a new perspective.

How do you know if any music or poetry is successful? Ah, well, that's a matter of taste. We've opened the door—and WLT intends to keep that door open, occasionally dropping some new sounds into these pages. Luckily, the totality of jazz—and poems about jazz—could keep you busy considering for a long time.

Santa Fe, New Mexico

Lauren Camp’s poems have appeared in dozens of journals, including Leveler, dirtcakes, New Verse News, andRhino, and she frequently collaborates with musicians to create multimedia performances. The author of This Business of Wisdom (West End Press, 2010), Camp is currently completing a second book of poems that explores the Jewish culture of 1940s Baghdad and its effect on her own upbringing. Her writing has been called “experimental” and describedas “mini-novels in poem form.”

Also a visual artist, Camp is perhaps best known for her series of large-scale jazz portraits constructed of fabric and thread, “The Fabric of Jazz,” which traveled to museums in ten cities. Her artwork can be found in cultural centers, hospitals, museums, U.S. embassies, and other organizations around the world.

For the past seven years, Camp has been a producer and host for KSFR-FM, Santa Fe Public Radio. After six years, she retired her popular Monday-morning show entitled The Colors of Jazz to broadcast Audio Saucepan, a genre-defying mix of music and poetry (Sunday evenings at 5pm mst).

Camp teaches creative writing through the O’Keeffe Museum’s Art and Leadership Programs, the Southwest Literary Center, Santa Fe Community College, and other schools, writers’ conferences, and organizations.

To learn more, visit www.laurencamp.com.