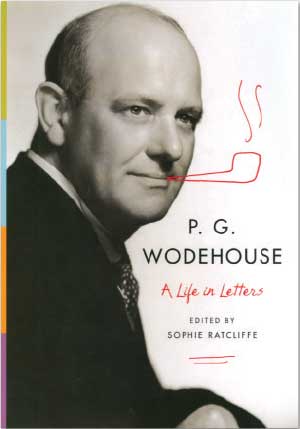

P. G. Wodehouse: A Life in Letters edited by Sophie Ratcliffe

Sophie Ratcliffe, ed. New York. W. W. Norton. 2013. ISBN 9780393088991

From P. G. Wodehouse’s first letter published in 1899 at age seventeen to the last, written (days before his death) in February 1975, Sophie Ratcliffe’s splendid editing presents Wodehouse’s life in his own words. In the three-quarters of a century of writing, we can see in the letters the author’s progression from schoolboy stories, through his work in musical theater as a lyricist, to his famously funny novels about the “mentally negligible” Bertie Wooster and his valet, Jeeves.

From P. G. Wodehouse’s first letter published in 1899 at age seventeen to the last, written (days before his death) in February 1975, Sophie Ratcliffe’s splendid editing presents Wodehouse’s life in his own words. In the three-quarters of a century of writing, we can see in the letters the author’s progression from schoolboy stories, through his work in musical theater as a lyricist, to his famously funny novels about the “mentally negligible” Bertie Wooster and his valet, Jeeves.

Wodehouse’s Broadway musicals, written with Jerome Kern, would alone have sealed his fame. But the public remembered and treasured his whimsical and entertaining novels like Right Ho, Jeeves, Quick Service, Blandings Castle, and Joy in the Morning.

There was, however, one dark and sinister cloud in an otherwise innocent life: during his internment in France during World War II, he was invited by the Germans to broadcast to the United States (not yet at war with Germany). His light and humorous talks described his life as a prisoner, meant to display British pluck to his countrymen, as he naïvely explained later. Wodehouse had no idea of the fury that exploded in England, with calls that he be put on trial for treason. He was reviled in Parliament and the press, his books were removed from library shelves, and there were even some public burnings of his works.

Ratcliffe is quick to point out that the letters are for the most part of a workaday nature, often bland and ordinary. Some letters do mirror the workings of the writer: Wodehouse’s desire to please his readers is clear in a letter where he writes, “We shall have to let truth go to the wall if it interferes with entertainment.”

The letters themselves are in various forms: handwritten and typewritten, telegrams, Christmas cards, postcards, notes, and even Nazi-censored cards sent during his internment. Recipients included Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Dorothy Sayers, Guy Bolton, Ira Gershwin, George Orwell, Malcolm Muggeridge, and Evelyn Waugh. An inveterate letter-writer, he often wrote a dozen a day.

But Wodehouse was not a good letter-writer, writing of his tax difficulties, his daily schedule, his pets (particularly his beloved “Pekes”), his weight gains. The letters are not particularly reflective, although they do display a sense of the time in which he lived and wrote. Explaining his method of writing a novel, he writes in one letter that he aimed to “mak[e] the thing frankly a fairy tale and ignor[e] real life altogether.” The letters show the politics of the man: his good nature, combined with naïveté and blindness, “a complete unawareness that anyone could be as ungentlemanly as the Nazis actually were.”

His letters are, as Ratcliffe points out, always warm, interested, and invariably concerned for the welfare of his correspondent. Indeed, this may be one of the reasons why his personal sense of politics is often so hazy: “He never seemed able to conceive of, or interest himself in, the notion of others in the context of any sort of group at all; his concern was wholly with the individual.”

Daniel P. King

Whitefish Bay, Wisconsin