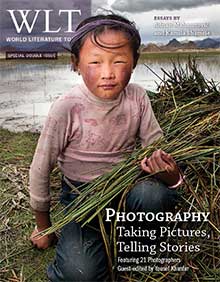

Tibet: Culture on the Edge

Last year, thousands of Tibetan students took to the streets to protest the Chinese government’s decision to conduct all elementary and high school education in the official Chinese language, Mandarin. China has recently mandated that all children go through grade nine and has plans to increase it to grade twelve soon. If Tibetan nomads fail to send their children to school, they get fined. In order to standardize the educational curriculum, smaller village schools are being closed and consolidated into larger boarding schools. Many rural children of farmers and nomads living far from the boarding school are only able to go home once or twice a year. It doesn’t take long to see how children cut off from their mother tongue would begin to lose their language.

To be fair, the Chinese government is not alone in wanting to standardize the language of its citizens. We in the U.S. have our own debates about bilingual education, and we have a history of brutally forcing Native Americans not to speak their native languages.

According to Ken Hale, a professor of linguistics at MIT, there are six thousand languages spoken on earth today, yet three thousand of them are not spoken by children. Every two weeks, another elder goes to the grave carrying the last spoken word of an entire culture. When the language dies, the culture dies. This is a silent extinction in that we scarcely hear about it in the media.

If you spend any time with the Tibetans, you will most likely realize, as I have, what a special culture they have. I have never been with a people that return a smile and laugh as readily as they do: having a cultural tradition and devotion grounded in compassion shows. If there was ever a good argument for a solid bilingual educational curriculum, this is it.

It’s not only educational policy that’s threatening Tibetan culture—today it’s the changing climate. The Tibetan Plateau, with an average altitude of fourteen thousand feet, is known as “The Roof of the World.” It has also been called “The Third Pole” because next to the North and South Poles, its glaciers contain the largest volume of fresh frozen water on earth. More importantly, it is known as “The Water Tower of Asia” since the rivers flowing out of those glaciers supply nearly a third of the world’s population with their water. Because of its combination of high altitude and low latitude, the Tibetan Plateau as a whole is heating up twice as fast as the global average and the glaciers are disappearing at an alarming rate.

In the northern areas, thousands of lakes have dried up, and deserts have grown to cover nearly one-sixth of the plateau. However, in the southern areas, the accelerating glacial melt has led to swollen rivers and much flooding. Almost all of the nomads and farmers I met complained about decreasing grasslands for their animals and erratic weather patterns that made timing the planting of their crops almost impossible. Living in one of the most fragile environments on earth, they are struggling to survive. I photographed several nomads next to the remains of glaciers they had lived near their entire lives. Returning to their summer grazing lands each year since they were children gave them a unique perspective on the accelerating pace of glacial retreat. Many of these glaciers had shrunk to a fraction of their former size in just a few decades.

The nomads and farmers on the Tibetan Plateau are truly the “canaries in the coal mine” with respect to climate change. They are now having their lives and culture disrupted by being relocated to resettlement camps. The looming catastrophe they portend will become all too evident as the glacier-fed rivers begin to diminish and leave millions or even billions of people downstream without enough water. Along with acute water and electrical shortages, experts predict a significant drop in food production, widespread migration of “ecological refugees,” and conflicts between Asian powers. Even though scientists disagree about how fast this will occur, all agree that it is happening.

Why should we care if these remote underdeveloped cultures disappear? Why does our species need six thousand languages? When I step from my culture into another, I notice things about myself I was unaware of. Being around the Tibetan values and beliefs caused me to reexamine my own culture. Evidence of the Tibetan daily devotional practice—a practice intended to expand their compassion to include all “sentient beings” and remind them of our “interconnectedness”—is seen everywhere. It’s the Tibetan recipe for well-being and happiness. The generosity, laughter, and singing I witnessed in yak-hair tents, fields, and monasteries, in spite of physical hardships and meager possessions, make me believe the Tibetans have something special.

It made me stop and ask, “What makes me happy?” How does my culture guide me in this pursuit? A diet of new cars, big houses, millionaires and billionaires, young beautiful faces, celebrities, and tons of stuff bombard me daily. This is what I’m encouraged to aspire to in order to set myself apart from the crowd! What a contrast to the Tibetan pathway that strives to dissolve the “illusion of separateness” by conquering the “self-cherishing” attitude. I think about my own personal ambition and desires and my culture’s dependence on ever-expanding economic growth and consumption—a dependence that is being exported to the rest of the world.

There is no doubt that the hospitals, schools, and communication infrastructure built by China in Tibet can enhance the well-being of the Tibetan people. By the same token, the Tibetan culture’s foundational ethic could provide the holistic perspective that today’s economies so badly need. In an ideal world, these very different cultures could beneficially share their values and resources and become a model for cross-cultural cooperation and ecological sustainability.

Yes, I have come to believe the Tibetan culture is “on the edge” and may disappear, but it isn’t alone in its precarious state. I recently learned that the United States has the most medicated, in debt, obese, and addicted adults in its history. Until we rebalance our capitalist model to equally nourish its participants, its community, and our planet, we will continue down a dangerous and unsustainable path.

Fortunately, there is a growing movement asking us to reassess some of our deeply held social and economic assumptions. This wake-up call is not only coming from scientists and academics but from pastors, psychologists, statisticians, artists, and youth groups. They are asking us to consider more effective paths to happiness and well-being—to authentically connect with others, give of ourselves, continue to learn, and take daily notice of the wonders that surround us. None of these activities stress the ecological health of our planet.

Being around the Tibetan people and their culture helped awaken me. Let’s hope that their magnificent culture will not only survive but thrive. I am reminded of the words of the Mexican poet and Nobel laureate Octavio Paz: “It is our ethnic and cultural diversity—our differences in language, customs, and beliefs—that provide the strength, resiliency, and creativity of our species.”

Seattle