“And Then We Went to the Brewery”: Reading as a Social Activity in a Digital Era

In our hyperdigital era, mass reading events provide opportunities for human interaction via a socially networked event that can be engaged online and offline, either once or repeatedly. These encounters may well be ephemeral, but they are capable of producing significant moments of identification or affective connection among participants.

Consider the following situations: We live in an era where people can communicate their ideas and feelings instantly to their friends via social media. At least we can if we have access to such devices as smartphones and tablets, and to communications technologies like 3G or broadband. Connecting with others so easily and sharing experiences—whether unique or mundane—is, we might say, a boon of our times, especially if we live our lives on a different continent from family and friends. We can socialize and be sociable across time and space faster and more frequently than we could even a decade ago.

Many readers enjoy exchanging their book recommendations, talking about the books they have read, and, given the opportunity, joining in conversations with successful writers. All of these ways of sharing reading have a long history in Europe and North America. They now occur both face-to-face and online, the latter sometimes enabled by the same platforms and devices mentioned above. And all of these reading practices are profoundly social acts.

Now contrast these two realities with Colin Robinson’s recent New York Times opinion piece in which he laments the difficulties facing the contemporary reader of books. “Today,” declares Robinson, “with our powers of concentration atrophied by the staccato communication of the Internet and attention easily diverted to addictive entertainment on our phones and tablets, book-length reading is harder [than ever].” Robinson goes on to argue that book reading is, moreover, a lonely endeavor because of the decrease in professional reading advisors such as reviewers who can provide “guidance,” the decline (in the US) of library use, and the shrinking quantities of publishers’ “midlist” titles.

Distracted, solitary, and reliant upon best-seller lists for reading matter: this is not a picture of the contemporary reader that we recognize. By contrast, we believe that readers are often social people and that reading is a profoundly social activity in several senses of that word. Even when we read silently and alone, we all have our own favorite places to read and preferences for what we read. These choices and inclinations are formed and informed by what the cultural sociologist Elizabeth Long has termed “the social infrastructure of reading.” What Long captures in this phrase is a wealth of structures that need to be in place for any one of us to become a reader, from our social networks (family, friends, professional contacts, for example) and socio-economic circumstances to the social institutions such as schools, governments, mass media, and publishers that put books—and our ability to read them—into our hands.

To advance this idea of the social reader still further, we would add the example of shared reading—that is, the various ways that readers share their experiences of reading with each other. Twenty-first-century readers—at least, those whom we have met in the course of our research—are adept at finding resources related to books through the connections they make with each other. Such connections are brokered through readers’ participation in various forms of shared leisure reading that can now include brief postings on Facebook or a quick click via one of the smartphone apps dedicated to logging what the user has just read.

Alongside these newer social practices of reading, face-to-face formations of shared reading such as book groups remain extremely popular. Just as the e-book has not killed off the codex, with e-books sales accounting for only 34 percent of market share in the US during 2013 (see Hazard Owen, “Digital”), so the urge for people to be social through their reading has not died in the face of technological change or as a result of the recent shifts in the book publishing and retailing industries described in Robinson’s New York Times article. To the contrary, we argue the reading practices that are facilitated through digital technologies support or enable readers to connect with one another in ways that we are just now able to identify and will likely continue in ways that we cannot yet imagine.

One particular means of people coming together to share their reading in public with both friends and strangers demonstrates how intensely pleasurable and profoundly social book reading can be in a digital age. One Book, One Community programs are large-scale reading events operating on a citywide or regional scale rather like a “supersized” book group. We have coined the term “mass reading events” for this type of shared leisure reading, and we would include other contemporary cultural productions that combine ambitious scale and a dash of spectacle within the same category. Television book clubs such as Oprah’s Book Club (US) and Richard & Judy’s Book Club (UK) perfected the combined use of television and online platforms to encourage readers to interact with the broadcast show and with one another. In Canada, the CBC Radio 1 series Canada Reads, which has been running annually since 2002, now broadcasts simultaneously across several platforms, offering readers the opportunity to participate and connect with each other via online forums, live Q&As with the panel of celebrity readers, and a Twitter feed.

We have also encountered wine tastings, group singing, visual art projects, and pub crawls, none of which depended on anyone actually reading anything, but all of which are predicated on the idea that a book can act as a cultural mediator or a kind of engine for social gatherings.

Meanwhile, the One Book, One Community model continues to be adopted and adapted around the world. Initiated in 1998 by Seattle librarians Nancy Pearl and Chris Higashi, One Book, One Community has proven to be a flexible and enduring form for shared leisure reading. As the name suggests, a book—often but not always a work of literary fiction—is selected as the focus for a series of activities within a city or region. The overall aim of the organizers is usually to encourage as many people as possible to read the featured book. Higher ideals, such as community building and encouraging cross-cultural understanding among different groups within a city, are also often expressed through the rhetoric publicizing the program or through the careful choice of venues for events. The lead organizers may be public librarians as they have been in the Seattle Reads and One Book, One Chicago versions, but other agents, including arts organizations, community groups, schools, universities, local governments, booksellers, and book publishers are usually involved as hosts, sponsors, or co-creators of events. Activities vary, and not all are as book-centric as you might expect. Some activities, like book discussions, assume that participants will read the book. Others do not, instead bringing people together for author events, bus tours around places related to the book, craft workshops, and even campouts, canoe trips, and themed cooking classes. Screenings of film adaptations, theatrical dramatizations, and staged readings of extracts from the book by professional actors or local celebrities are common to various iterations of the model. We have also encountered wine tastings, group singing, visual art projects, and pub crawls, none of which depended on anyone actually reading anything, but all of which are predicated on the idea that a book can act as a cultural mediator or a kind of engine for social gatherings.

Although it is impossible to provide an exact figure, we estimate that more than five hundred One Book, One Community programs take place annually around the world. According to the Library of Congress, there are hundreds of community, regional, or statewide reading programs in the US alone (www.read.gov/resources). Between 2006 and 2012, the National Endowment for the Arts sponsored over a thousand One Book, One Community programs through its Big Read project, which aims to put book reading “at the heart of American culture” (www.neabigread.org). Canada is home to at least five long-running annual One Book, One Community programs, including One Book, One Vancouver, with many others taking place over the past ten years as one-off events. The picture is similar in the UK with Liverpool Reads leading the way. Through our work, we’ve heard of similar programs in the Netherlands (Nederland Leest), Sweden (Uppsala Läser), and Australia (One Book, One Brisbane), just to name a few.

The readers who participate in mass reading events (MREs) actively seek the re-mediation of their reading experiences not only through different media but also through other readers. The various pleasures that these readers derive from their participation in some of the “live” events that form part of many MREs can tell us much about the social, cultural, and emotional “uses” that readers make of face-to-face events. What the investigation of MREs in the US, Canada, and the UK has shown us is the desire that many keen readers have to replay and transform their own reading experiences. Readers achieve this re-mediation through listening to and engaging with each other’s emotions during a “live” event and even through their own bodies by visiting a place or landscape associated with the featured book. Sharing reading is thus a cognitive, affective, and somatic activity. It’s profoundly social and can be intensively felt in body and mind as well as being entertaining, fun, and informative.

“It’s so nice to be with other people who are appreciating the same thing. And then we went to the brewery,” Anna told us through stifled laughter. A reader from Ontario (Canada), Anna was referring to her One Book, One Community experience. You might ask what this has to do with reading a book. We asked the same thing. From this statement, we know that Anna went on an outing with a group of people, enjoyed the company and the sharing of some kind of experience or object, and then rounded off a fun day with a brewery tour and (presumably) a beer. Anna, a middle-aged white woman, is actually reflecting on her participation in a literary bus tour around sites associated with Jane Urquhart’s novel The Stone-Carvers (2001), which was the 2003 selection for the One Book, One Community program in her area. Taking Anna’s words out of context, as we have done here, underlines what we believe to be a crucial factor that helps to explain the popularity of contemporary shared reading events: they are a form of entertainment, well suited to the time-pressured environment of twenty-first-century everyday life.

The most successful MREs—from Oprah’s Book Club to Canada Reads to long-running One Book, One Community programs in Chicago and Seattle—exploit the opportunities to produce multiple encounters with books. Equally significant to their success as entertainment, MREs extend the possibility for multiple encounters with other people. In Huntsville, Alabama, for example, we met many readers who attended numerous events hosted by the programming committee centered on Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird. But a number of these readers were also accessing information about books online and using digital tools as a means to connect with others via literary blogs and readers’ reviews. Sara, an avid reader and stay-at-home mother, told us how the Internet “has really opened up the world” for her. This conversation took place in 2007, before Facebook or LibraryThing became popular websites for readers. Yet Sara already articulated the benefits of using nontraditional literary resources to enhance her reading experiences. “Over the past few years, there’s so much available on the Internet,” she said. “So much literary information. And it’s all free; it’s all on there. You just type it in and find out; that has helped me find out about books more than anything.” Further along in our conversation, Sara told us that attending multiple events focused on To Kill a Mockingbird enabled her to exchange information specific to the book with other people. “I guess it’s just something that I can’t get anywhere else,” she told us. “I tend to like to go to those events because you just can’t get that information anywhere else, you know? It’s just different.”

What we came to recognize by talking to Sara and hundreds of other readers in the US, Canada, and the UK was that what was “different” about face-to-face reading events went far beyond the pleasure of learning new information. In our hyperdigital era, MREs provide opportunities for human interaction via a socially networked event that can be engaged online and offline, either once or repeatedly. These encounters may well be ephemeral, but they are capable of producing significant moments of identification or affective connection among participants.Being moved by a writer’s performance or another reader’s shared interpretation, seeing your imagined community temporarily but physically realized in your local sports hall, and feeling as if you belong somewhere even within a group consisting mostly of strangers are among the profoundly social experiences that readers have articulated to us.

When reflecting on a 2005 Seattle Reads public event that highlighted Julie Otsaka’s novel When the Emperor Was Divine (2003), event producer Chris Higashi reflected on the audience, which included members of Seattle’s Japanese American community:

So we had 130 people squished into the room, and they were everywhere! But he [the group leader] said, “Um, can I ask those of you who were interned to please stand?” And you know, these people are not people who are used to calling attention to themselves, and so they rose very slowly: thirty of them from around the room. And the room—oh, you could just hear the sigh! And then, people applauded and cried. I mean, it was unbelievable; it was so moving. Yeah, I mean, every time I tell this story, you’d think a year later I could do it without weeping.

Higashi’s reflection works as testimony on two levels. First, there is her own witnessing of Japanese American seniors, including her own aunts, having their experiences acknowledged and thus being recognized by all those present. Second, there is the public, community recognition or witnessing of the internment experience. While there is no proof of long-lasting social change occurring as a result of the occasion, Higashi’s narrative indicates the radical potential of the One Book, One Community model when it brings people together to discuss issues that some participants might find emotionally upsetting or to explore ideas and experiences that unsettle normative social relations, official histories, and institutional structures. In such circumstances, the book itself is a social artifact, and the shared reading of it becomes a form of cultural mediation that is not only ideologically dynamic and disruptive but also potentially creative and even politically empowering in terms of permitting citizens agency.

In Bring on the Literature for Everyone (2010), Jim Collins adeptly outlines how the consumption of re-mediated literature becomes recoded as an authentic cultural experience. He proposes that the production and delivery of literary fiction through various sites, media, and texts have led to what he calls a “complete redefinition of what literary reading means within the heart of electronic culture.” Media convergence and new technologies of delivery have created a series of new taste formations or lifestyles. The early-twenty-first century convergence of media, or an “interdependency of print and visual culture,” as Collins describes it, means that readers engage with these literary formations and lifestyles in a series of cross-media ways—online, at the cinema, and via the television to name just three. Within these busy media landscapes, new guides have emerged, offering advice about what and how to read. We do not disagree with Collins, but we found in our discussions with readers, and keen readers in particular, that “it’s hard to teach an old dog new tricks.” That is, readers still make value judgments about new cultural authorities such as Oprah Winfrey and Nancy Pearl and the books they review and recommend. In addition, the medium through which a reader experiences a book has an influence on their attitude toward their judgment of a book and the medium through which the book is interpreted. Our research shows that readers tend to believe various forms of media possess different cultural values, and sometimes they perceive them as serving different cultural functions. The cultural value normally assigned to the different media—radio and television—and the genres employed within those media influence readers’ perceptions and interpretations of the kinds of reading each MRE promotes.

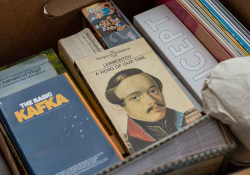

Discussing the re-mediation of books through readers themselves, or through digital technologies, risks ignoring the book as a material object. And we were impressed with the physical relationship readers had with their books. At virtually every public event, readers touch and caress their books, particularly while listening to an author speak. This physical response to the materiality of the book can have various meanings, ranging from an unconscious display of the emotional comfort a book provides to a conscious exhibition of “good taste.” Within our discussions, readers reveal a profound physical and emotional attachment when describing their books and the place of reading in their lives. This in turn demonstrates that the book evokes a powerful response in its devotees, and that, to speak more broadly, the book as object remains both meaningful and culturally significant in the contemporary moment. There is a special place that reading occupies—and that the codex book maintains—in an era of media digitization that is evolving noticeably from one week to the next.

We think that one of the reasons why reading literature remains a popular leisure activity, and why there has been a “resurgence” in shared reading practices—or, at least, widespread recognition that shared reading serves individual needs as well as the public good—is because the book in its codex form still has a special status. The act of reading, commonly viewed as credible and significant, imbues the codex with symbolic power in contemporary Western culture. Whether the interpretation of the book takes place in a virtual space or in a face-to-face setting, the book remains a cultural artifact, and the interpretation of it is a process of cultural and social mediation that can tell us much about living in Western society during revolutionary times.

When we began our project nearly a decade ago, we named it Beyond the Book to emphasize our interest in what readers make of books and reading them. The experiences we observed and those described by readers themselves forced us to return to the notion of “the book.” The physical sensations inspired by paper, binding, and covers; the physiological relationships with the codex; and the pleasures and distinction associated with sharing the reading experience are complicated in an era when reading experiences are available in different media and formats. Although the future of the codex form may be in question, what isn’t in question, for us, is the possibility of pleasure that shared reading events make possible, the profoundly social nature of those shared experiences, and the fact that shared reading is a social practice with a future.

University of Birmingham / Mount Saint Vincent University

Together, they published Reading Beyond the Book: The Social Practices of Contemporary Literary Culture (2013) in Routledge’s Research in Cultural and Media Studies series. More information about the five-year international investigation that resulted in this book can be found at the project’s website (beyondthebookproject.org).

They are currently working on a reading app that will continue to connect readers and help us all to better understand the role of reading in contemporary readers’ lives.

WORKS CITED

Collins, Jim. Bring on the Books for Everybody: How Literary Culture Became Popular Culture (Duke University Press, 2010).

Hazard Owen, Laura. “Digital Now Makes up 11.3% of Hachette’s Revenues Worldwide, and 20% of Random House’s Paid Content.” Gigaom Research, August 30, 1013.

Long, Elizabeth. Book Clubs: Women and the Uses of Reading in Everyday Life (University of Chicago Press, 2003), 16–17.

Reinking, David. “Valuing Reading, Writing, and Books in a Post-Typographic World.” In The Enduring Book: Print Culture in Post-War America, vol. 5 of A History of the Book in America (University of North Carolina Press, 2009), 485–502.

Robinson, Colin. “The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Reader.” NYTimes.com, January 4, 2014.