Srebrenica and Rwanda, Twenty Years After: Poetry as Renewal in Marjorie Agosín’s Mother, Speak to Us of War

To read a poem is to hear it with our eyes; to hear it is to see it with our ears.

Octavio Paz

Writing mostly of those whose survival was completely—or remains nearly always—under threat is at the heart of Marjorie Agosín’s poetry.[i] Poetry about peoples or countries in conflict, under political distress, or on the brink of extinction might signal certain attempts to preserve their spiritual survival, remember repression-ravaged existences, or pay homage to those who once existed. Reading imaginative texts—which have been inspired by war- or postwar-affected individuals—might also inspire us to think of such individuals’ fortitude to stay alive. One thing is certain: most prose or poetic imaginative texts that beam latent or more explicit realities of terror can quite instantly inspire complex forms of remembrance. As revealed in her corpus that spans nearly three decades, Agosín often views poetry as a medium for renewal. Her war-inspired poetry often cuts deep into the most vulnerable tissues of her poetic entities’ consciousness, thus inviting the reader to imagine carving out possibilities for preventing losses or dealing with mourning or remembrance. Agosín’s Mother, Speak to Us of War / Madre, háblanos de la guerra (2006) is punctuated by such mnemonic revivals. By choosing a small poetic sample from this collection (“Srebrenica,” “Rwanda” and “Where Will Their Dreams Go”), the reader may unearth a cross-cultural and dynamic matrix of mutually distant afflictions, but also intimately sought remembrances through motherhood. Reading these poems as an interactive triad, on the other hand, may reveal them as an aesthetic instance for generating a mnemonic account of human rights in anticipation of the twentieth anniversary of the genocide in Rwanda and Bosnia in 2014 and 2015, respectively.

Juxtaposed in an interactive mode—whereby each of these poems can be read as mutually interactive—this poetic triad offers a mnemonic account of the abject failure to preserve basic elements of human dignity.

The Conscience Damped with Guilt: An Interactive Poetic Triad

Much of Agosín’s verse in Mother, Speak to Us of War exhibits a photographic quality by dint of a mnemonic response to both concrete and less easily recognizable contexts of our recent pasts. Out of the three poems selected here, two (“Srebrenica” and “Rwanda”) stand out with mnemonic vigor through a number of unmistakable images that most readers recall instantly upon reading these two words. They evoke the easily recognizable sites of some of the most appalling human rights violations in the last quarter of the twentieth century. The third poem, “Where Will Their Dreams Go,” centrally evokes the fragility that survivors or younger generations inevitably face in their post-apocalyptic ruins existentially in whatever context they may come to inhabit. Juxtaposed in an interactive mode—whereby each of these poems can be read as mutually interactive—this poetic triad offers a mnemonic account of the abject failure to preserve basic elements of human dignity.

Where Will Their Dreams Go

Marjorie Agosín

In the hills

Beyond the mad wind

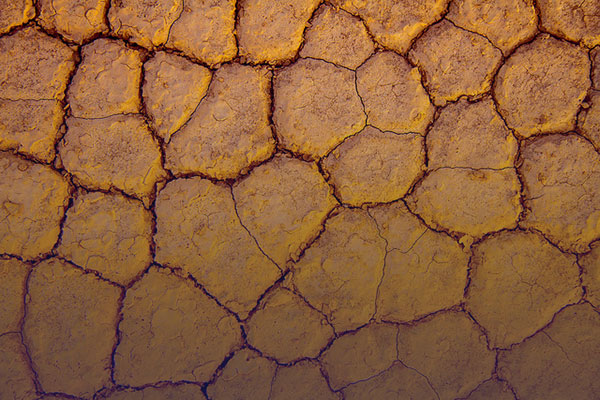

In the cracked earth

In the vast darkness

The children play with war’s remains

Weapons

Bones

Skulls

Eyeballs

The children playing for so long a time

With war’s pieces

Learn too the hatred

That spreads between the horizons

Where not even the dead rest

And I ask myself

What will become of those children

With whom will they play

Will they be soldiers themselves

Where will their dreams go

Agosín’s poem “Where Will Their Dreams Go” is physically situated in the midst of a collection that contains forty-one bilingual (Spanish and English) poems. The reader enters the poem as if it were a post-apocalyptic terrain: “In the hills / Beyond the mad wind / In the cracked earth / In the vast darkness.” The first step is an overwhelming and asphyxiating experience, going both up high (“hill”) as well as cutting through the earth’s entrails (“cracked earth”) under the heavy lack of light and folly gusts. The permanence of this nightly ambiance is echoed in its vastness, beaming through every bit of the represented space. Yet the next verse only seemingly appears to announce some glimmer of light as we read “the children play.” By reading these words we might experience a letup or might anticipate a relief from the dark we have been navigating through so early, vastly and deeply into this poetic terrain. But these children swiftly figure in as an offspring of the unnamed apocalyptic demise, for their play focuses solely on “war’s remains.” If treated as a textual link between the other two poems, this image of “war’s remains” firms up its emblematic meaning, inviting us to imagine the aftermath of, above all, human destruction at the universal level. Agosín’s seemingly dispassionate clarification of such “remains” (“Bones / Skulls / Eyeballs”) is an image heavily impregnated with the myriad of symbolic possibilities: war or postwar ruins of the animate and inanimate spirit; the unresolved or hurt-ridden pasts; the present crowded with concrete human loss. The straightforward naming of the presumably human (or animal) body parts—“Bones / Skulls / Eyeballs”—may not be solely symbolically indicative of the mass graves across Bosnia’s Srebrenica or Rwanda’s spaces of “blood and soil,” but may dissolve into a latent reference to other sites where the aftermath of human destructions have been deposited: Chile’s Atacama Dessert of the 1970s; the clan cleansing sites in Somalia; Argentina’s ocean depths of the 1970s; or the events that inspired Picasso’s Guernica, to name just a few.

These references to mostly decomposed bodies, in poetically photographic snapshots of sorts, have not solely seeped into the false lightheartedness of the children’s play but are buried much deeper toward these children’s own consciousness. Indeed, they have seeped with the potentiality for an odious seed: “With war’s pieces / learn too the hatred / that spread between horizons / Where not even the dead rest.” One could read this verse as a symbolic marker of how repositories of evil can congeal inter- and cross-generationally beyond a present darkened with the destruction’s aftermath. If this poem serves as an intertextual bond between the other two poems, then one of the most obvious yet unmentioned implications in it must be genocide.

In this context, Alexander Hinton’s discussion of genocide comes to mind immediately regarding the dissemination of hatred. According to Hinton, at the heart of all genocidal blueprints rests the premeditated notion of deeply harmful social polarizations. Hinton furthermore specifies that genocides are “distinguished by a process of ‘othering.’” He further explains that in this process, “boundaries of an imagined community are reshaped in such a manner that a previously ‘included’ group [. . .] is ideologically recast [. . .] as being outside the community, as a threatening and dangerous ‘other’—whether racial, political, ethnic, religious, economic, and so on—that must be annihilated.”[ii]

Hinton’s observation is particularly relevant when we read that the hatred runs the risk of fossilizing itself against the poem’s children and their potentially amity-focused dreams: “And I ask myself / What will become of those children / With whom will they play / Will they be soldiers themselves / Where will their dreams go.” The poem, therefore, ends not with the images of dismembered human flesh and bones but its less palpable—yet equally potent—aftermath, thus implying the potential for future lethal “othering.”

Rwanda

Marjorie Agosín

Have you ever thought about the orphans of Rwanda

Who play with broken bodies

In a land that devours everything

Who go from village to village

Looking for the skulls of other children

Skulls now deposited on tables of soldiers

As trophies of war

Have you ever thought of the mothers of Rwanda

Have you ever thought of how this happened

How we watched the people die of grief

From far away

Always from far away

Measuring the consequences of our complicity

From a distance

If “Where Will Their Dreams Go” puts children at center stage as a trope for nearly any war-affected or postwar generation, Agosín’s “Rwanda” pulls the reader into a very specific sociopolitical and cultural matrix.

If “Where Will Their Dreams Go” puts children at center stage as a trope for nearly any war-affected or postwar generation—faced with its own challenges of stitching together their present and daring to dream of their future—Agosín’s “Rwanda” pulls the reader into a very specific sociopolitical and cultural matrix, what Ben Kiernan describes as “the Land of a Thousand Hills.”[iii] Yet once the reader reaches the last verse of this poem, she sinks deeper before the weight of the questions that hold the poem together. Addressing mostly those absent (conceptually, physically, or perhaps both) from the place the poem straightforwardly names, this poetic expression falls heavy on the passive bystanders’ conscience. It does so in one breath. In its entirety, “Rwanda” is perhaps a deliberate list of interconnected and punctuation-free questions. Although the entire collection is written in the same punctuation-free style, this poem’s structure—its airy openness that runs through the entire poem mostly structurally upheld by the verse that stands alone in the poem’s midst—sets a particularly torrential tone. If the previous poem may have referred to the children of warring parties, survivors, perpetrators, heirs, and/or the future, this poem’s central focus may be the cut-up motherhood and lethally interrupted childhoods: “Have you ever thought of the orphans of Rwanda / [. . .] Looking for the skulls of other children.”

The last stanza centers on moments when we are faced with the suffering of others, perhaps echoing Susan Sontag’s Regarding the Pain of Others (2003), especially those afflicted outside of one’s immediate scope. In fact, as it unfolds into “Have you ever thought about how this happened / [. . .] / From far away / Always from far away” these verses retrospectively may be implying what might be called a benumbed empathy. The fact that we subsequently read “the consequences of our complicity” may suggest that we remember a largely collective failure to empathize enough. In their joined introduction to Humanitarianism and Suffering: The Mobilization of Empathy (2009), Richard Wilson and Richard Brown underscore the importance of understanding one’s own rights in order to empathize with others. Their lengthier explanation is worth quoting in its entirety: “Suffering is a universal human experience, [and] potentially all individuals can connect emotionally to specific people and their woes. In contrast, in order to empathize with the deprivation of the rights of others, one must posses a vivid sense of one’s own rights.”[iv]

Published twelve years after the genocide in Rwanda and revisited in the present essay on the twentieth anniversary of that genocide in 2014, this poem, too, enters the permanent commemorative fabric of the sociocultural context it bears. Its language, although replete with universally recognizable existential anguish in post-annihilation contexts, does not lapse into exaggerated sentiment. Reading this poem in 2014, as part of larger commemorative undertakings, allows for further strengthening of what Wilson and Brown straightforwardly call “recreating functioning social selves” (Wilson and Brown 21). Yet unlike the venues that carve out testimonial territories for victims’ postwar subjective remembrances, this poetic piece figures as an empathic memory without emotional excess.

Srebrenica

Marjorie Agosín

In Srebrenica

Death knocks at the door

Without the rhythms of song

Certain that no one will come again

To this place in Srebrenica

Only an echo

Echo echo echo

Memory is a gust of absence

Words do not reveal

They silence

Language vanishes

In Srebrenica

This evening

When death

Returns to your house

Like “Rwanda,” Agosín’s poem “Srebrenica” was published a little over a decade after the genocide in Bosnia.[v] Unlike “Rwanda,” this poem reads mainly in the present tense, as if written while the genocide was unfolding: “In Srebrenica / Death knocks at the door,” pulling us into the moment of the indiscriminate mass killings. Reading it upon the twentieth anniversary of the genocide in 2015, the reader may experience an uncanny present-past moment: simultaneously being in this re-created present of the killings while recalling them through this unfolding commemorative piece. Commenting on Tess Gallagher’s remarks that “poems work as time machines that sustain us in a world where technology has reduced our sense of past and future to ‘an instantaneous now,’” Penelope Pelizzon responds by ascribing a conceptually swelling attribute to poetry. “Poems,” explains Pelizzon, “offer the possibility of bringing past, present and future together by creating a space where that ‘now’ can expand.”[vi] The piercing second stanza cuts to the heart of the deaths smeared over soon to be largely a ghost town, whereby we recall Feldman’s discussion on the “unthinkable,” which seeps into the “unspeakable,” yet screams loudly through the ubiquitous stillness that inhabits these verses: “Memory is a gust of absence / Words do not reveal / They silence / Language vanishes / In Srebrenica / This evening / When death / Returns to your house.”[vii] In The Body in Pain (1985), Elaine Scarry underscores that violent acts threaten language, which ultimately can paralyze it. These threats, in turn, prevent it from capturing such acts in all their complexity. Yet reading these verses, in memory of the indiscriminately perished, functions at two interconnected levels. First, “Words do not reveal / They silence / Language vanishes” seems to confirm the power violence holds to incapacitate language. Yet the rest of that same stanza establishes an implicit discursive counterweight, “When death / Returns to your house,” thus inviting the reader, through these six weighty words, to begin reimagining such encounters and their fatal implications. And certainly without veering into sensationalism, the poem rapidly ends, extending itself into an abundance of silence.

Silence, as a multifaceted experience or a communication, remains an overwhelmingly potent element in Agosín’s poem “Srebrenica.” The sole sound (and therefore movement) in the poem remains linked to the activity of fatality: “Death knocks at the door / [. . .] when death returns to your home.” With its determined and constant presence, death leads to the repetitious echoes of silenced, abandoned, or fragmented spaces that may be harboring collective horror, individual foreboding, or existential disquiet. The implied silence in the poem “Srebrenica” becomes particularly potent when juxtaposed to a scene from the PBS-sponsored documentary Srebrenica: A Cry from the Grave (1999).[viii] The scene shows a visibly shattered father, who had been captured together with another group of Muslim men in Srebrenica by Serb general Ratko Mladić’s troops in July 1995, calling for his son. His teenage son, Nermin, as we soon learn through the documentary narrative voice of Bill Moyers, had managed to hide in the nearby hilly forests around Srebrenica before the Serb military troops initiated their genocidal undertakings. Forced to call his son to come out of the forest, a forest that served as protection from the subsequent slaughter, the father essentially calls for his son to proceed into harm’s way. After each cry the father makes, waiting for the son to emerge from the woods’ protective thickness, the viewer experiences a moment of dead silence in that sweltering summer afternoon in July 1995. This silence in the documentary fills up these profoundly thorny, tense, and perturbed moments of a coerced intersubjective interaction: the father’s certainly unwilling cries to hasten his son’s imminent annihilation and the son’s persistent threatening of the father’s immediate survival. Each of them was ultimately threatened with losing his life if he remained silent. Against their will, these men end up forced to betray each other head on and lastingly. The initial silence—or quiet resilience—on the son’s part defies easy definition but ultimately merges into the genocide’s aftermath itself as they both end up indiscriminately killed. The echoes of such silence have reached Marjorie Agosín as well, turning themselves into a lasting commemorative poetic account.

Beyond the Poetic Triad: Assaulted Motherhood?

Mother, Speak to Us of War unambiguously suggests, in its very title, an urge to remember such affliction-ridden pasts, through motherhood above all. “Remembering,” as Paul Ricoeur reminds us in Memory, History, Forgetting (2004), “is not only welcoming, receiving an image of the past, it is also searching for it, ‘doing something.’”[ix] This “search” comes forth in this collection fundamentally between the universally relatable and juxtaposed interlocutors: mothers and vastly unidentified others. Motherhood is foregrounded from the outset through the presentation of particularly unenviable conditions of loss, remembrance, and commemoration. Motherhood is, quite simply, assaulted. Assaulted motherhood, rudimentarily viewed through this poetic collection, might be understood as a multifaceted condition of abuse. It entails boundless violent physical, emotional, or psychological mistreatments of mothers meant to reverberate through future biography. Reading this collection as a whole, one sees that assaulted motherhood emerges from traumas through rape; fragmentations through the kidnapping, torture, or ultimate elimination of women’s offspring or their family members; or fatally endangering those who make up the nuclear family of mothers. Assaulted motherhood across these verses consequently becomes an emblematic crux for war-related afflictions of the recent pasts and, in some cases, still largely unsettled present.

Mother, Speak to Us of War brings before us mothers’ voices from the Holocaust, Hiroshima, Argentina’s Dirty War, the Pinochet era in Chile, the Spanish civil war, Afghanistan, and the September 11th attacks.

Yet Agosín’s Mother, Speak to Us of War simultaneously situates the mothers’ voices in an assertive position. The collection announces that these mothers’ words, stories, accounts, narratives, memories, or experiences boldly infuse these poetic expressions not solely to bear witness to the disastrous past or present but to refuse to assume a position of abeyance. In addition to the Rwandan and Srebrenican mothers’ confrontations with the past, Mother, Speak to Us of War brings before us mothers’ voices from the Holocaust, Hiroshima, Argentina’s Dirty War, the Pinochet era in Chile, the Spanish civil war, Afghanistan, and the September 11th attacks, to mention some of the most noticeable ones. With each poem about these (and other) sites of terror—and sometimes places of survival—the reader must confront a particular set of mnemonic complexities at once or individually through assaulted but also unvanquished motherhood.

Reflecting on trauma through the written, spoken, or cinematic lens nearly always runs the peril of being reductive, softened, or simplified. Despite such perils, though, certain depictions can still allow a deeper glimpse into the complexities an atrocity might entail. As a consequence, the act of portraying traumas, regardless of the aesthetic mode, predictably disallows that the latter be silenced into oblivion. While the two poems’ titles evoke, quite directly, the relatively recent sociopolitical traumas from Rwanda and Bosnia, the third poem, “Where Will Their Dreams Go,” bonds “Rwanda” and “Srebrenica” by accentuating the universal relevance regarding tender attempts to comprehend, connect with, or commemorate the distressing voices of wars beyond the Rwandan and Bosnian contexts. In reading poetry that commemorates certain losses, we are also actively invited to engage commemoratively with other indiscriminate killings, destructions, and human rights violations prior, across, and beyond the twentieth century.

Wellesley College

[i] Marjorie Agosín (b. 1955) is a poet, short-story writer, literary critic, and human rights activist whose literary production has earned her numerous awards in the United States and abroad. I thank Marjorie Agosín for the interview time she granted in December 2011 and December 2013 at Wellesley College.

[ii] Alexander Hinton, “The Dark Side of Modernity: Toward an Anthropology of Genocide,” in Annihilating Difference: The Anthropology of Genocide, ed. Alexander Hinton (University of California Press, 2002), 6.

[iii] See Kiernan, Blood and Soil: A World History of Genocide and Extermination from Sparta to Darfur (Yale University Press, 2007). According to the Institute for the Study of Genocide, “Losses occurred at different levels (human, physical, and psychological) and have strong social repercussions. In our 1995 survey, 97% of survivors interviewed had lost a close relative. According to government estimates, nearly one million people were killed, 400,000 of whom were children. Up to 120,00 children were orphaned and as many as 85,000 households are now headed by children.” For more information see http://www.instituteforthestudyofgenocide.org/oldsite/newsletters/25/athanse.html.

[iv] Richard Ashby Wilson and Richard D. Brown, eds. Humanitarianism and Suffering: The Mobilization of Empathy (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 12.

[v] In 2007 the International Court of Justice (ICJ) ruled that the execution of nearly 9,000 Muslim men and boys by the Bosnian Serb military was an act of genocide.

[vii] Allen Feldman, “Memory, Theaters, Virtual Witnessing and the Trauma-Aesthetic,” Biography 27, no. 1 (Winter 2004): 163–202.

[viii] See this documentary in its entirety at http://www.pbs.org/wnet/cryfromthegrave.