Overnight, 130,000 People Flee Cuba for the United States and Defeat Jimmy Carter and Bill Clinton

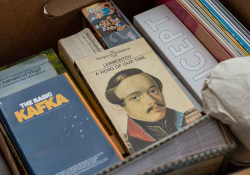

The following excerpt is from The Last Soldiers of the Cold War, by Fernando Morais, forthcoming Verso Books (on sale wherever books are sold on June 16, 2015). Roberto Fernández Retamar included Morais’s book in his “What to Read Now” recommendations for understanding contemporary Cuba.

Migration crises were far from a novelty in the harsh and tumultuous relationship between the United States and Cuba after Fidel Castro came to power in 1959. The first of these arose shortly after the triumph of the Revolution and lasted until 1962—a period in which 200,000 people, almost 3 percent of the Cuban population, departed for the United States. The exodus produced a sharp demographic leap in Miami, whose population rose from 300,000 to almost half a million. Up until the Cubans’ arrival, the census registered that out of every ten local residents, eight were white and only two “nonwhite,” a category that included blacks and Hispanics. Although the first wave of migration included torturers from the Batista government, drug traffickers, bookies and pimps, statistics showed that the great majority was made up of liberal professionals—above all doctors, given that health was one of the first sectors nationalized by the revolutionary government—as well as businessmen, bankers, landowners and industrialists who had had their property expropriated. The components of this first wave fostered the illusion that what had happened in Cuba was just one more Latin American military coup. The coup d’état backed by the CIA in Guatemala six years earlier, when President Jacobo Arbenz had been overthrown after decreeing an agricultural reform program that affected the interests of the American multinational United Fruit Company, was still fresh in everybody’s mind. The United States would never tolerate a communist government in Cuba, 160 kilometers from its coastline. “Entire families, with their servants and dogs,” wrote the Cuban specialist and academic Jesús Arboleya, “embarked for Miami in the hope they would soon return home.”

Cubans still lived with the trauma of the mass escape organized when the Catholic Church joined forces with the opposition. At the height of the first confrontations between Havana and Washington, the CIA and the archbishop of Miami, Coleman Carroll, orchestrated a dreadful plan for the mass transfer of children from Cuba to the United States with the indispensable support of the Cuban Church. Christened Operation Peter Pan and later inspiring books and films, the action began on an October night in 1960 with a distressing proclamation from an announcer on Radio Swan, a station set up by the CIA in Miami to broadcast programs to Cuba: “Cuban mothers! The revolutionary government is planning to steal your children!” cried the announcer. “When they are five, your children will be removed from your families and only come back again at eighteen, transformed into materialist monsters! Watch out, Cuban mothers! Do not let the government steal your children!” The second step came the following morning when hundreds of thousands of pamphlets were scattered throughout the country with the text of a fictional law, written by members of the CIA, that would allegedly be put into effect “at any moment” by the Cuban government. Packed with legal considerations, the apocryphal document was signed “Dr. Fidel Castro Ruiz, Prime Minister” and by the then president of the Republic, Osvaldo Dorticós. The threat that would terrify mothers and fathers appeared in three articles and two paragraphs:

Article 3 — . . . From the date of implementation of the present law, minors below the age of twenty will become wards of the State.

Article 4 — . . . Minors will remain in the care of their parents up to the age of five, from which time their physical, mental and civic education will be entrusted to the Children’s Circles Organization, which will be responsible for the guardianship of the aforementioned minors.

Article 5 — . . . With a view to their cultural education and civic training, from the age of ten years onwards, any minor may be removed to a place more appropriate for the attainment of such objectives, always taking into account the best interests of the nation.

Paragraph 1 — From the date of publication of this law, it is prohibited for all minors to leave the country.

Paragraph 2 — Noncompliance with the precepts contained in the present law will be considered a crime against the revolution, punishable by imprisonment from two to fifteen years depending on the gravity of the offense.

The man chosen by the archdiocese to carry out the plan was Bryan Walsh, a six-foot-tall, fifty-year-old Irish priest with the body of a boxer, who had lived in the United States since his youth. Arriving in Havana a few weeks after that October night, carrying in his baggage no less than 500 blank entry visas to the United States, Walsh found a society in a state of shock. The denials of the revolutionary government had done little to soothe the fears of Cuban families. In addition, parish priests all over the country, especially in the countryside where the less-educated population lived, took it upon themselves to spread the gruesome rumor that the children separated from their parents were to be removed to Moscow and transformed into canned food for consumption by the Russian population. It was not the first time that such a ghastly and implausible story had been used for political ends. The anecdote about communists eating people had been born at the end of World War II, when the fascist propaganda machine flooded Italy with leaflets affirming that Italian soldiers who surrendered to the Red Army would be killed, ground up and fed to the starving millions in Stalinist Russia.

Towards the end of 1960, the Cuban Revolution had already implemented radical changes such as agrarian reforms, the nationalization of the banking system and the “forced expropriation” of almost a thousand industries, among which were a hundred sugar mills and some giants like the Bacardi rum factory and the American DuPont chemical company. In spite of the revolutionary nature of these measures, when Operation Peter Pan was conceived Cuba and the United States still maintained normal relations. Hundreds of travelers crossed the Florida Straits daily in both directions, on flights that connected the Cuban capital with Florida; the air bridge between Havana and Miami was the route chosen by Bryan Walsh to put the operation into practice. The CIA demanded children should not be accompanied by their parents. The 500 blank forms the priest had taken on his first trip would not be enough, as it turned out, to cover even 5 percent of the little candidates for salvation from the communist hell. Many years later, Fidel Castro would comment on the episode in a television interview. “We thought that the Revolution should be a voluntary act on the part of a free people, and we placed no restrictions on departures from the country,” recalled the Cuban leader. “The response of imperialism, among other hostilities, was the implementation of Operation Peter Pan.”

According to the American NGO Pedro Pan Group, altogether 14,048 girls and boys were smuggled out. Some would become distinguished figures in American public life, like Republican Senator Mel Martínez, Tomás Regalado, the former mayor of Miami, and the diplomats Eduardo Aguirre, nominated as ambassador to Spain by President George W. Bush, and Hugo Llorens, ambassador to Honduras in 2009 at the time of President Manuel Zelaya’s deposition. Initially put into Catholic orphanages and charitable institutions, thousands of these evacuated children would never see their fathers and mothers again. The beginning of 1962 saw the end of Operation Peter Pan, one of the most dramatic and painful episodes of the Cuban Revolution. The third wave of migration occurred at the end of 1966, after President Johnson signed into law the Cuban Adjustment Act— which was simply the legal recognition of a situation that had existed since 1959 and survived under the complacent eye of the American authorities. Without parallel in any other country, the law offered Cubans arriving in the United States, even if illegally, privileges not conceded to foreigners of any other nationality. The benefits offered by the government were a tempting invitation: political asylum and documents granting permanent residence. In other words, authorization to work and claim social security—rights that were extended to spouses and to children below the age of twenty-one. It was the opposite of the treatment dispensed to the hordes of Latin Americans who tried to enter the United States via the Mexican border. In the four years to follow, an air bridge linking the seaside resort of Varadero to Miami carried more than 270,000 Cubans.

The fourth and noisiest crisis began on the afternoon of April 1, 1980, when six Cubans invaded the mansion that housed the Peruvian embassy in Havana, hurling a bus against the garden fence. The only impediment to entry, a lone soldier guarding the doorway, was gunned down. Minutes later, once inside the house, the six were declared political refugees. Cuba demanded that all of them be returned, since by killing a soldier they had become common criminals. The Peruvian ambassador, however, would not budge: his country had decided to grant them political asylum. The gravity of the situation put Fidel Castro in direct confrontation with General Francisco Morales Bermúdez, head of the Peruvian government, who had toppled the similarly ultranationalist General Juan Velasco Alvarado in 1975. On receiving the six invaders as asylum seekers, Bermúdez imagined he had Fidel in a corner with no way out: were he to concede safe conduct for the group to leave Cuba, the government would be setting a serious precedent, that in order to get out of the country, all it would take was to set foot inside an embassy, even if it involved violence. But to deny permission would turn those six Cubans into martyrs, and once again brand Cuba a country that violated human rights. All of these outcomes had the potential to cause a diplomatic impasse with unpredictable consequences. What General Bermúdez could never have imagined, however, was that Fidel would react with an extraordinary decision. The response came in a short article published on the front page of the April 4 edition of Granma, which ended in an unusual way:

In view of the Peruvian government’s refusal to hand over the delinquents who caused the death of the soldier Pedro Ortiz Cabrera, the Cuban government reserves the right to withdraw the embassy’s protective guard. The diplomatic mission mentioned, therefore, is open to all who wish to leave the country.

What seemed to be an isolated incident turned first into a commotion, then a stampede, and two days later there were 10,000 people camped out in a six-bedroom residential property. Frightened by the presence of the rabble that had taken over every inch of the house, Ambassador Edgardo de Habich abandoned the premises, taking with him his entire diplomatic staff except for his business attaché, who became responsible for the legation. Two weeks after the occupation, and with the swarm of people still inside the embassy, Peru capitulated and admitted it was unable to receive 10,000 people at a moment’s notice.

It was at this point that Jimmy Carter entered the fray. Of all the occupants of the White House since the triumph of the Cuban Revolution, Carter was the one who maintained the best relations with Cuba. He had been responsible for lifting all the restrictions on the exiles for travel to the Island and for the creation of the Interests Sections in Havana and Washington so that, in his own words, “a minimum of diplomatic exchange could be carried out.” In July 1977, in an interview with the Brazilian magazine Veja, Fidel recognized that something was changing in the United States. “Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson, Nixon and Ford were committed to a policy of hostility towards Cuba,” affirmed the Cuban president to the weekly, “and this is the first US government in eighteen years that is not committed to that policy. Nixon was a buffoon, an individual without ethics of any kind. I don’t think the same of Carter.”

Three years after these declarations, however, the domestic scene in the United States had changed a lot. The conservative American majority had fumed at Carter’s treaties with the Panamanian president Omar Torrijos, pledging to hand over control of the Panama Canal in 2000. Public opinion also considered Carter to have been soft on the USSR for ignoring the 1979 invasion of Afghanistan by Soviet troops. But what would put an end to his popularity happened on the night of April 25, 1980, when the White House–approved Operation Eagle Claw ended in catastrophe. Aboard eight helicopters and six Hercules C-130 planes, ninety men from a USAF antiterrorist commando took off from the Kingdom of Bahrain and from the aircraft carrier Nimitz, anchored in the Indian Ocean. The operation’s objective was to set free fifty-two Americans taken hostage six months earlier by a group of young Iranians who had occupied the United States embassy in Tehran. Thrown off course by sandstorms in the Dasht-e Kavir desert, already in Iranian territory but still 500 kilometers from the capital, the mission was aborted when one of the helicopters crashed into a transport aircraft. Eight American soldiers died, and the hostages remained in the hands of the Iranians.

The crestfallen survivors of Operation Eagle Claw returned to Washington nineteen days after the Peruvian embassy in Havana had been taken. In the face of the timidity shown by the international community—Peru agreed to receive only 1,000 of the 10,000 people who had taken refuge in the embassy, Canada 600 and Costa Rica 300—the American president, who would run for reelection in October of that year, thought that here was an opportunity to recover his popularity. Contrary to the moderate diplomacy he had adopted in relation to Cuba since he came into the White House, Carter called a press conference and announced a bombshell. With the new name of “Open Hearts and Open Arms,” the old Adjustment Act was resurrected: all Cubans who managed to reach the United States would receive political asylum, permanent resident status, permission to work and to register with social security, and the rest.

Translation from the Portuguese

By Robert Ballantyne with Alex Olegnowicz

Editorial note: First published in English by Verso 2015. Translation © 2015 by Robert Ballantyne with Alex Olegnowicz. First published as Os últimos soldados da guerra fria, © 2011 by Companhia das Letras.