Transmutations of / by Language

Raha Namy contemplates what it means to live and write in the border spaces of translation, wandering between the motherland and the adopted land, traveling to and fro between the mother tongue and the second tongue, forever navigating worlds and words, not finding a definite home in any one.

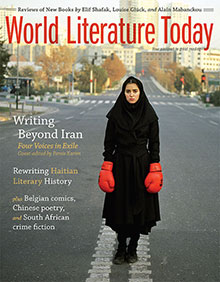

My Homeland Iran, by N. Kasraian.

Persian carpets and kilims are spread under their feet. The Persian food cooked by mothers and grandmothers is desired even by third generations. Calligraphy tableaus in Persian hang on their walls. Photographs from the good old days back home decorate their houses. Poetry nights are held to recite Hafez and teach Rumi. Persian pop songs make their bodies sway in Eastern moves. Blue plates and bowls filled with salted nuts sit atop their coffee tables.

On the blue walls of their Facebook pages, you have come to notice, however, that many Iranians living in diaspora write in English. They live not only with their own people but also among others, speaking other languages, mainly English, and they need to communicate. But it is not just the posts aimed at different members of the new society, coming together in this shared new world and finding meaning in this shared language, that they write in English. They write in English even in posts specific to Iranian friends, in comments to Iranian friends’ updates and feeds. Sometimes they write in Pinglish, rarely using the Persian alphabet. Many know Persian. Many, though, have not learned how to type in Persian or do not even have the option of Persian language on their laptops and other devices. You notice that you too have a hard time thinking about and writing some statements in Persian. You make a conscious effort to keep the language present on your page, in your communications, in your life.

* * *

In an American city, an Iranian man expresses love to his American girlfriend by beginning an email with, in Pinglish, “Asheghetam,” which means “I love you” in Persian. Othering the language of love, he is making it exotic and arousing, taking her into this other unknown land; but he is also bringing the other into his first language, into this previous other world of his, making it accessible to her, creating a bond, an intimacy.

In an Iranian city, an Iranian woman texts her Iranian boyfriend, addressing him as “بیبی ,” which is “baby” written in the Persian alphabet. In bed with him, her language for the demands of the body is English. She cannot articulate the equivalent words in Persian. She finds them vulgar, unacceptable, unladylike. The English creates distance, as if it’s not she who is speaking them but another, making the words okay to be uttered out loud. She doesn’t even have the Persian words to mouth. Her knowledge of sex and eroticism is in the language of the other. She has learned it from movies, mostly American, in English. Persian is castrated through cultural and official censorship.

You, an Iranian woman living in an American city. Your lover, an Iranian man living in an Iranian city. He and you speak in Persian, email in Persian, make love over Viber in Persian. You, the translator who constantly moves between English and Persian, the writer who writes in English, do not want any translations in this intimate space.

It was in your relationship with an American lover a few years ago that you came, for the first time ever, face to face, with the failures of translation/migration on a deeply personal level.

On that winding road connecting the two foreign cities and in the singer’s voice, you suddenly come to the realization that parts of you will forever remain untranslatable to this man from the other language, from the other country, which are nonetheless yours, but only forever partially; and parts of his to you.

Once on a drive from Washington to Baltimore with him, the two of you listen for a while to the Iranian female singer Googoosh and then for a while to Bruce Springsteen and keep switching back and forth. Listening to Googoosh’s songs, which you have grown up with since early childhood, you get goose bumps and he gets restless and irritated. You try to translate the words of the songs and the memories revived by them, and you fail; and even when you succeed everything sounds stupid and banal and you come to hate this partial sharing. You are not unfamiliar with Bruce Springsteen, but he doesn’t touch you the way he does your lover. On that winding road connecting the two foreign cities and in the singers’ voice, you suddenly come to the realization that parts of you will forever remain untranslatable to this man from the other language, from the other country, which are nonetheless yours, but only forever partially; and parts of his to you.

Once he reprimands you for not wanting to accompany him to a stadium to watch a baseball game with him and his coworkers, for not being open enough to learn about his culture. You reply in anger that you are living his culture, every aspect of it, every day, every night, every damn second. And he . . . ? He has a choice for the what and when and how of his exposures and adoptions.

It is in that lover's simultaneous desire for and impatience with your foreignness, and in your own desire for and resistance to his, that you realize that, no matter what, your culture and your country will be the one always remaining in the margins, in the distance, an intellectual concept, a faraway reality, and that you will forever have a limit for how far you can, or want to, go into and settle in his. With your failure to navigate this personal in-between, you begin to fall into a deepening void. You try to force yourself to find home in this new land and language, but you keep failing, and the gap continues to grow inside you.

It was in your relationship with an Iranian lover in Tehran a few years ago that you came to realize for the first time that a lack of sufficient knowledge of English could be a hindrance in your togetherness with the men from your first country and language.

Your lover is a culturally savvy, well-read, movie-enthusiast architect, and the two of you have much to talk about, to think about, to share; but one night in bed, in the calmness and long hours of the dreamy wakefulness after lovemaking, while the two of you talk about work, you suddenly notice that you need to paraphrase and summarize for him the stories that you write in English. His English not being good enough means that reading your work demands an extra effort, and it won’t just happen as another natural part of your shared space. It hurts thinking that he is a foreigner to a significant part of your being, a world you inhabit even when you are not typing the words.

You split your life between the States and Iran, moving across the borders, and you have lovers speaking this or that language. You keep losing your bearings more and more every day. You grow obsessed with belonging and longing, become consumed by wanderlust, trying to rebuild or rediscover home. It takes a long while and a lot of tearing your past and present and future apart and digging continuously deeper and deeper into your identities to finally come to the realization that you are not going to find a home anymore in one place or person or language.

* * *

You came to writing through learning English as a second language while growing up as a kid in Iran, because writing was one of one the main tools your English tutor used for teaching. The first essay you were asked to write, when you were ten or eleven, was in answer to the question: “What would you like a ship to bring you?” You have kept that piece. Its paper is yellowing and the corners are disintegrating. The pencil-written words are fading, from black to gray to less and less visibility, disappearing into the many drawers the paper has been put into, into the seconds of time piling up in between its original moment and its continuous existence, into the transfigurations of the girl who wrote it and the woman who keeps holding on to it.

You write for your English classes: book reviews and summaries, movie criticism, essays, etc. You watch bootleg English movies, pronounced illegal by the government, rented out weekly by movie men delivering them door-to-door in briefcases and bags. Later on when illegal satellite channels become accessible, your main source of news becomes the English news outlets. You grow up reading world literature in translation and Persian literature heavily influenced by world literature and translation. In a book market where, due to the lack of copyright laws, you find dozens of translations published for many of the world masterpieces; where the name of the translator is published next to the author’s on the book cover; where translators create ways around the official censorship to give you versions of the original works (believing that something is better than nothing), you come to understand the significance of the translator’s role, appreciating his/her labor of love.

The pencil-written words are fading, from black to gray to less and less visibility, disappearing into the many drawers the paper has been put into, into the seconds of time piling up in between its original moment and its continuous existence, into the transfigurations of the girl who wrote it and the woman who keeps holding on to it.

You continue your English class, writing and reading regularly, until you are eighteen and your tutor retires. You choose English<>Persian translation as your BA major, and from that first year, you begin to freelance as a translator, translating into your mother tongue. You begin learning French, again having a teacher who has you memorize stories, watch cultural documentaries and feature films, and write essays regularly. You continue your studies and get an MA in translation studies. At some point you begin translating into your second tongue.

* * *

Despite the translations and the French writings, a while after graduation, you find yourself yearning to write again in English. You begin to ask around for teachers who offer advanced classes specifically for writing.

A coworker who hears of that yearning sends you an email, suggesting a writing challenge. What he really wants is to get you in bed. You are naïve and don’t read between the lines, or you do and think you are beyond that, in control, and you accept the challenge. But then life explodes. Not that he is the reason; many other things happen and he is just there in the right moment (or in the most wrong one, based on which perspective you choose). You go from a woman happily married to the love of her life to a woman still in love with her man, but not in love with marriage and the life she is having; a woman who, lost and confused, doesn’t want to let go of the thrill of new stories being written and of writing them.

The lover holds your hand and takes you into the madness of the world of words. The two of you meander through unknown neighborhoods of the city, making love in friends’ houses, in the brackets of time stolen from your virtuous realities. And then you go back to the arms of your husband, finding yourself capable of giving him even more love now that you are feeling revived, now that you do not need him to give you what you need to survive. And yet you find yourself hating yourself, hurting deeply from the secret duality, from moving between one and the other.

You are lost and confused about the meanings and capacities of love, its challenges and responsibilities, are sure only about one thing: you wish to live with words and stories, both in the reality of the world and on the page. You apply to a creative writing program. You reveal your truths to both men. You try to cling to both men. You and your husband don’t really work out. You and your lover don’t really work out. You wish to hold on to both the old and the new, but the more you try the more you fail. You finish the master’s degree. A few years after you apply to a PhD program. You keep writing.

* * *

You write your first-ever real story in English in your fiction techniques class. About a girl growing up during the Iran-Iraq War who becomes a journalist. Worried about the imminent threat of another war, irritated by a brother who has built home elsewhere, she does not want to leave her city under any circumstances.

That it was your first-ever real story is perhaps not totally true. You have writings before that that are stories. You just did not know that what you were writing were considered stories.

You never wrote in Persian and it is only recently, years after writing in English, that you begin to write in your first language, not yet stories, but drafts, notes, and essays. But that too is not totally true.

You diligently kept diaries as a teenager. In your undergraduate program, you wrote for a Persian literature class. One work was a collection of vignettes, one of which was a scene from a weekend in a cemetery. Working as a translator, you also wrote a few original short pieces in Persian for journals here and there. In retrospect, you see them as mediocre and insignificant, but they have familiar threads of your writing today. Perhaps they were the first steps you were taking in the world of words without knowing you were taking them.

Interesting thing is that in elementary and middle school, you hated writing your composition homework. You begged your great uncle to write them for you, and he would help you with generating ideas and doing research but refused to write them—except that one night, when you left his room almost in tears, angry with him because he was making you sit into the late hours of the night and do it all alone, only to find in the morning that he had a complete essay ready for you on your desk.

People keep asking you about the choice of language. You know but don’t really know. You write in English because you have practiced writing in English more systematically and more regularly. Because you have had great teachers in your nonnative languages who have made you read and write and watch, a lot, who have corrected you, you have helped you grow one step at a time. You write in English because the already existing canon of Persian authors terrified, and still terrifies, you. You never had that concern about English because whatever you did was good enough for you, this being the foreign faraway realm. Because you enjoyed the learning, the dictionary and grammar challenges, seeing your improvement little by little. Because it was through the necessity of learning this other language that reading and writing became inseparable parts of you.

* * *

If language is home, do homes come in different accents? If one of your languages is written from right to left and the other from left to right, then are the homes you inhabit mirrors of one another?

For many writers, especially for expatriates and exiles, the first language is/becomes home. But if language is home, then what happens to you and others who work with several languages, finding it exhilarating to move from one to another, not getting settled in one or the other? Do you find several homes? Or do you lose all homes, living in dualities, becoming a wanderer in the space of borders, finding life only in disparate patches, some on this side, a few on the other, some beyond, a few close by? If language is home, do homes come in different accents? If language is home, is that home in the meaning or in the transcript? If one of your languages is written from right to left and the other from left to right, then are the homes you inhabit mirrors of one another? Clashing with one another? Or simply different? If language is home and home is identity, does that mean you are forever torn between the multiple “you’s” in multiple languages?

You want to believe there is home beyond language, beyond thought, beyond representation. You want to believe there is home somewhere regardless, somewhere without. You keep questioning and writing more and more about the meanings of home, the sources of identity, the consequences of language.

* * *

You leave the US for months to go back to Iran, because you need to feel, breathe, smell, touch the first land, live the stories in the first language. You leave Iran for months to go back to the US, because you learn and build in the second land, write the stories in the second language. While in the States, you surround yourself with Iran and the Persian language and arts. While in Iran, you surround yourself with the English and French languages and foreign arts.

Recently, you are becoming aware of a growing new sensation: wanting to move to a new land that will surround you with neither this nor that language, with yet another language. A place that will force you to face once again the challenge of coding and decoding, building language consciously and with effort, understanding it and not understanding it, simply trusting the still inaccessible sounds and forms to take you away into new mysterious territories. You are feeling the urge for yet another unknown, a place whose foreign oral environment will mirror your inner turmoil of constantly feeling like being an outsider, a foreigner, no matter where, not fully belonging in the first or the second land, in the first or the second language, forever needing to flow.

* * *

Bodies flowing from one place to another for not good-enough reasons are looked at suspiciously by governments, entities, and individuals who want the world in clear-cut borders and definitions. They have a problem with gypsies and nomads and natives. People who move with the seasons, following the rhythms of nature, permanently setting up temporary homes. People who do not believe in possessing and demarcating land but in coexisting with it. People who believe in more elastic definitions. They force nomads and natives to settle in place. They appreciate them but only as part of a past, exotic and historic, celebrating them in glass boxes, as if objects in a museum. They turn their lives into tourist attractions, the material for festivals and souvenirs. Civil men draw lines, finding identity in nationalism and patriotism, attaching themselves to land and place. That is how they learn and teach history, how they create memories. That is how they become the “we” against the “others” on the other sides of those arbitrary lines. That is how they exist.

The trans-dwellers have always been trespassers. And trespassers are betrayers, not of this group, not of that group, always to be watched, always to be kept distant.

But even nomads and natives who do not belong to land and borders define themselves with belonging to tribes and clans. There have always been “we” vs. “others.” Identity has always been closely tied to belonging, to being one of a definite whole. The trans-dwellers have always been trespassers. And trespassers are betrayers, not of this group, not of that group, always to be watched, always to be kept distant.

And trespassers who move in between countries/groups whose leaders come to identify one another as enemies are regarded as more of a threat. Being from a country of the “Axis of Evil” makes you more suspicious than the rest of the citizens in the land of the United States. Being from the land of the “Great Satan” makes you more suspicious than the rest of the citizens in the land of the Islamic Republic. The governments of both the host country and the motherland want you to either belong to this or to that, not to be constantly in motion between the two. It doesn’t matter whether you are a physicist or a journalist, an artist or a doctor, a businessman or a student, or simply a tourist; it is politics that define and decides the limits and the righteousness of your transitions between borders.

* * *

In the transborder extensions of your body and mind, you keep losing established relationships and you keep finding new ones. Some men tell you that at some point you need to choose, to settle. Others understand the wandering but find it a concern regardless, a problem for developing deeper relationships. And then he happens. He who seems to know, to understand, without your needing to delve into language to explain. He is from the first land and speaks the first language and the second, but more importantly he speaks your language of life that you keep carrying with you from one set of alphabets io another, from one geography to another.

As you try to gradually prepare yourself, mentally and emotionally, for the possibility of becoming an exile if you get to publish your books (because of their sexual political content), you begin to develop an urgent desire for having a man by your side in the new lands and languages who is of your first land, sharing your collective past, knowing your culture, feeling (and not just understanding on an intellectual level) your concerns, speaking your language. You want him to keep you connected to the language and to the place. You want to hang onto him and to home through him.

You want to believe that he himself can be home, is home. But . . . but then, why don’t you want to settle in him? Why do you want the two of you to be always one step away from one another, your bodies remaining borders of your beings? Can he be home in the moments he is inside you and you are around him, when his being is taking your being toward coming, toward becoming . . . ? Or can he be home even when away, far far away?

You want him. You want him and still you cannot bring yourself to settle down, in one world or another, in one language or another, in one man or another. You want him and you are afraid because you do not want to lose another man to this constant longing to leave. You know it and he knows it too: even in him you won’t find a home. You will forever remain a wanderer, a woman in constant trans who knows the moment she finds a home she will die and the home will die, a woman who constantly needs to fly away, but only to be able to come back.

* * *

You have a complicated relationship with airports.

Tehran airport is the threshold of belonging vs. nonbelonging for you, the last stop before departing the only home you have ever known, the only city you felt whole in for many years, until you did not anymore. The airport is also the space that offers you one last immersion in the mother tongue, as the official all-embracing oral and written alphabet that you are constantly exposed to unconsciously in the homeland, before you fly into the authority of other languages and need to make an effort to abstractly and consciously surround yourself with it. The Tehran airport is for you a marker of forced separations, a structure for the accumulation of all burdens of goodbyes.

You hate the Tehran airport and the US airports when they are your points of arrival/departure from the other land. You can never get used to the weight of official uniforms, the coldness of their voices and gazes. You can never be sure what kind of welcome or adieu you will get. They are the space of governments, not of people and the open embraces that await you beyond them.

It is in the Tehran airport that he kisses you goodbye only after four days and nights of being lovers, and it is then and there that you feel there is something different about him. Only a week or so later, sitting at your Denver apartment, the sun and the blue skies wrapped around your nakedness, you ask him, lying in bed in the darkness of the night in his Tehran apartment, whether he would accompany you to unknown worlds. He says he would. No pauses. No hesitations. The two of you plan to meet in a few months in a third city.

Airports of third countries are soothing spaces to you. In them you can feel the outside world and your inner one consolidating. They are the true representation of translation and transition. It is in these spaces of in-betweens and nonbelonging and temporariness, where everyone is a stranger, heading one way or another, speaking one language or another, that you can simply be. Out of place. Out of time.

It is in one such airport, in a city that is not yours or his, where both of you, in the course of a two-week sojourn, begin to learn new, unfamiliar words while you try to find your way around the right turns and the wrong turns of the alleys, around the curves and touches of each other’s bodies, that you try to break away from him before you each fly back to your city, you to the West, he to the East. The two of you have, from the first moment, promised each other polyamory, a relationship without set borders, a commitment to continuous expansive organic translations and retranslations of togetherness. And even with that, fearing a solid presence and a structure, you try to break up all ties with him before it is too late to go back to your now familiar writerly self.

But he is not having any of it. He sits on the other side of the table as the two of you drink your cups of Turkish coffee, turning them around to wait and read your divinations, and he tells you he is not going anywhere, that he will be staying by your side, that he wants to be the man of yours to whom you keep returning, not the man who wants you for himself, who wants you to stay. As you hear the name of the city you are flying to amidst the words of the language you don’t understand coming through the loudspeakers, followed by the announcement’s English translation, you decide to trust those words spoken in Persian by this still-unraveled man in the mother tongue and set off on yet another wandering, wishing to rediscover more of the unknown, in the world, in him, and in yourself.

Denver, Colorado