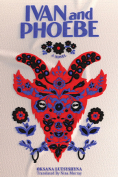

Ivan and Phoebe by Oksana Lutsyshyna

Dallas. Deep Vellum. 2023. 425 pages.

Dallas. Deep Vellum. 2023. 425 pages.

Oksana Lutsyshyna’s Ivan and Phoebe tells the story of Ukraine’s early independence through the eyes of a disillusioned romantic from the far western city of Uzhhorod. Divided into three parts, the story is told out of sequence. Part 2 is a flashback to Ivan’s participation in the Revolution on Granite, a student-run hunger strike that mostly took place on Kyiv’s Maidan, not yet famous for its subsequent revolutions. The first and third parts of the story focus on Ivan and his unhappy homecoming after feeling forced to leave Lviv, the city where he studied and had at one time seen his future. Back in his mother’s realm, Ivan is only going through the motions of living, further entrenching himself in a life he’d thought his education and experience would help him escape.

Herself a native of Uzhhorod, Lutsyshyna is able to offer us a vivid portrait of a Ukrainian city that is rarely depicted in art. Local color comes in the form of Ivan’s brother-in-law, Styopa, an eternal schemer whose salvation finally arrives as an abandoned Soviet bus; Ivan’s mother, Margita, and her sisters, Ondia and Ildia, who love to curse, gossip, and cook in the Hungarian of their youth; and childhood friends Kreitzar and Yura Popadynets, who are determined to raise Transcarpathia to its feet, be it through goat herding or Ruthenian independence. The complexity of regional politics over the last two hundred years also comes through, with people who essentially agree with one another on the big points—no to tyranny!—while debating the finer details and secret histories.

Ivan and Phoebe fills a very important lacuna in Ukrainian literature—especially what is available in English—by portraying the important role the student revolution of 1990 played in achieving Ukraine’s independence from the Soviet Union and forging a democracy mindset among Ukrainians, one that would serve them again and again over the next four decades (though it could be equally argued that the mentality was already there and was what made the students’ protest possible). There is also the character of “Sashko Petrenko,” a former KGB man now working for an unknown boss. Besides literally pursing Ivan, causing him such torment that his life spins out of control, he offers another type of psychological torment: despite the clear example Ivan has from the Maidan of ideals being made manifest and resulting in real change, he begins to doubt anything can ever change in a meaningful way. This fear is confirmed when, for example, a student leader “falls” off the back of a moving train or an optimistic politician seeks the favor of a crooked Orthodox priest.

It’s not hard to see why Ivan and Phoebe won both the Taras Shevchenko National Prize in Literature and the Lviv UNESCO City of Literature Award. Most esteemed Ukrainian literature from the 1990s was written by sanguine young people who saw independence as an opportunity to be carefree and write roguish prose and poetry, often at the expense of their former colonial power, but rarely plumbing the challenges of real life. The book succeeds at painting a picture of volatile young Ukraine during the “wild” 1990s when capitalism made no sense in the context of a formerly planned economy and unscrupulous individuals were taking advantage of all the confusion. Ivan and Phoebe shows us that all this turmoil had real effects on the lives of people who couldn’t count on a salary, had mouths to feed, and still had complex psychological lives they couldn’t straighten out. Basically, their hierarchy of needs came crashing down all at once.

Still, the emotional tenor of the book is a bit confusing at times and not always convincing. For example, without knowing what happens in part 2, it’s hard to understand why Ivan feels so scared in part 1. Furthermore, although the novel explores the ills patriarchy wreaks on men, the perspective feels lopsided: Ivan is so denied agency that he’s never asked to take responsibility for the violence he himself perpetuates. More of Phoebe’s voice would have been welcome and less of her life filtered through Ivan’s perceptions of her.

Ali Kinsella

Chicago