Balancing Melancholy and Joy in the Work of Japanese Poet Misuzu Kaneko

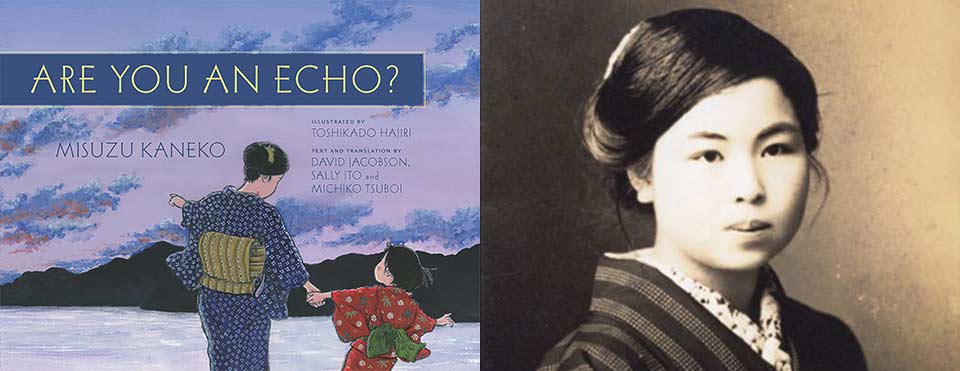

Misuzu Kaneko (1903–1930) is a poet who holds a special place in the hearts of many Japanese as a voice of compassion in a difficult time for the country. The recently published Are You an Echo? The Lost Poetry of Misuzu Kaneko (Chin Music Press, 2016) is a beautiful book that features a selection of her poetry—poetry that was nearly lost to time. The book begins with a brief narration of Kaneko’s life alongside a few relevant poems and then moves solely into her poetry, featured in both English and the original Japanese.

Misuzu Kaneko (1903–1930) is a poet who holds a special place in the hearts of many Japanese as a voice of compassion in a difficult time for the country. The recently published Are You an Echo? The Lost Poetry of Misuzu Kaneko (Chin Music Press, 2016) is a beautiful book that features a selection of her poetry—poetry that was nearly lost to time. The book begins with a brief narration of Kaneko’s life alongside a few relevant poems and then moves solely into her poetry, featured in both English and the original Japanese.

Kaneko’s poetry is primarily for children, as is the book itself, which is why I admire the decision to not shy away from the heavier topics in the narrative of Kaneko’s life. Kaneko’s later years were marked by tragedy; she faced down her husband’s infidelity, became ill as a result, and committed suicide in order to ensure that her daughter would not be raised by the man. Refusing to include this would have denied the beauty in resilience that abounds in her poetry. The insight into Kaneko’s tumultuous life adds another dimension to her work, making the bittersweet moments in her poetry even more powerful.

One of the biggest strengths of Kaneko’s poetry is the way that she emulates the endless power of the childlike imagination.

The narrative portion of the book approaches these issues in a tasteful manner—it doesn’t gloss over tragedy, but presents it in a way that children can meaningfully engage with. This allows for children to encounter some of the unfortunate realities of the world and opens up frank, honest dialogues between children and their parents or guardians. These events certainly don’t comprise the bulk of the book; in fact, the majority of the book is hopeful.

In the face of these tragedies, neither the narrative nor the poetry lapses into despair but instead often strikes a balance between melancholy and joy. Take her poem “Cocoon and Grave,” which reads:

A silkworm enters its cocoon—

that tight, uncomfortable cocoon

But the silkworm must be happy;

it will become a butterfly

and fly away

A person enters a grave—

that dark, lonely grave

But the good person

will grow wings, become an angel

and fly away

For Kaneko, there is beauty and hope even in death, something she sees as merely a transition. Her poetry approaches this sadness with her trademark wide-eyed wonder, transmuting it into something manageable.

Her poems are marked by a sophisticated simplicity that inspires reflection in the smallest of moments. The language and structure are not overly complex, which has the dual effect of making the poetry accessible and slipping readers into the unspoiled and unashamed mind-set of a child. One poem, “Day and Night,” contains only five modest lines:

After day comes night,

after night comes day.

From where can I see

this long, long rope,

its one end, and the other.

Yet with these short, unassuming lines, Kaneko asks questions without the reticence that adulthood too often instills. Her understanding of life becomes a solid image in the minds of readers through the form of the rope—it’s not difficult to grasp and still sparks a moment of pause and thought.

One of the biggest strengths of Kaneko’s poetry is the way that she emulates the endless power of the childlike imagination. The poems urge younger readers to cling to their childlike wonder and allow adults to recapture that sensation by making familiar moments and objects somewhat strange. Objects as banal as a rock in the middle of the road or a telephone pole at night become subjects with rich inner lives and histories. The world as we know it is turned on its head and suddenly becomes something full of possibility and opportunity at every turn, where snow can feel “burdened” and “lonely” and the “waves are forgetful.”

The translators of the book, Sally Ito and Michiko Tsuboi, have been faithful to the source text. The original Japanese poetry mimics the speech patterns of a young Japanese girl—a style unmistakable in Japanese but difficult to emulate in English. Their translation retains these elements without sacrificing any of the depth of the source material, resulting in the complexity of adult sagacity superimposed on the voice of a child.

Finally, the book itself is simply beautiful. The artwork by Toshikado Hajiri is lovely and done in a style that reflects the culture of the content’s origin. Colors pulse throughout the book with the same warmth and care that was put into the poetry, evoking the same sense of childlike wonder as the words. When color is absent, it brings a profound sense of stillness that reaches beyond the poem.

A deep kindness and warmth fill these pages, leaving readers with a sense of the tenderness that Kaneko approached the world with. The book is a wonderful testament to a poet who holds a special place in Japan. Its handling of tragedy and encouragement to observe the world in different ways makes it a perfect book for a young child—for adults, it serves to momentarily return that sense of awe at the world.

University of Oklahoma