On the Intricate and Fathomless: Shadab Zeest Hashmi’s Comb

I first met Shadab Zeest Hashmi at AWP in March 2019, when we both participated in a panel of Pakistani American poets writing in English. On a rainy night, she and her sons came to pick me up for dinner. The other panelists, poets Raza Ali Hasan and Faisal Mohyuddin, were already in the car. The six of us were one too many for the five-seater, and with nowhere to park, we were all forced to quickly cram ourselves into the car. It was after we had haphazardly arranged ourselves that we finally had a chance to see each other’s faces and say salaam.

The plan that evening was to discuss the next day’s format, but instead we lost ourselves in conversation about Urdu, Faiz, Ghalib, Qawwali, and Agha Shahid Ali. It was as though a hunger was being sated—I had never been so excited in a poetry setting. Eventually, and inevitably, our conversation brought us to the idea of “home,” that locus of longing for the estranged poet. After several seconds, I offered: “Home exists only in memory,” though I was dissatisfied by my own abstraction.

*

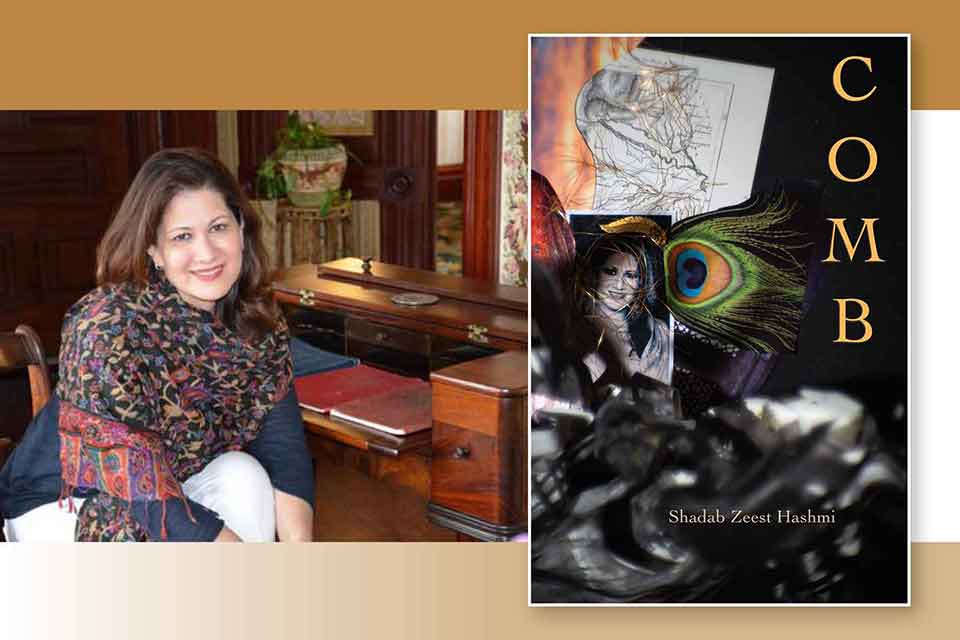

Shadab Zeest Hashmi’s Comb (Sable, 2020) grapples deeply with the idea of home—both in physical space and in the mind. A winner of the Sable Books Hybrid Book Competition, the hybrid memoir is composed of essays, poems, and photographs. The book also features stunning artwork by UK-based artist Salma Caller. For Zeest Hashmi, home is a place of peace—a sanctuary for the weary body, a space to untangle the mind and bring it to rest. In this search, Zeest Hashmi touches transience; adorning Comb are moments of epiphany and divine awareness. Her prose is a delicate fabric—gauzelike—that rises like a wave crest, catches the light, and again loses itself.

As we read, we are Zeest Hashmi’s confidantes—the ones she entrusts with her secrets as she undoes her mind’s tangles. And perhaps her instrument, her “comb,” is language itself. For what is writing, what is speech, what are words, if not simulacra, means to detangle our complexities of thought, the intricacies of self?

Hidden in rituals of grooming and caregiving are words spoken only when we’re unguarded. These are the rare moments we’re physically in the hands of an unconditional love whose touch stimulates a unique language based on trust, opening the chute of memory or mystery . . .

The deepest, most treasurable conversations ensue: the person being massaged may suddenly recall a forgotten incident, a song fragment, a joke, an old story or a snippet of family history, or may enter a contemplative space, a different dimension of consciousness or of long-guarded secrets. (“Shampooing”)

A tangling: the perplexity and imbalance that comes with bilinguality and the inheritance of multiple literary traditions, a kash ma-kash, a search for “self” within what seems almost to be a binary. In truth, there are two selves that long to know one another, but remain severed, strangely, by the fact of imperialism. Our terrible fate is to have been born at this crossroads: to share the language of both tyrant and oppressed.

Our terrible fate is to have been born at this crossroads: to share the language of both tyrant and oppressed.

Inheritors of multiple languages inevitably are tasked with translation, if not in the conventional sense of the word, then at least in the intangible processes of the mind. Each moment, we decide which way we want to live, and what values we will align ourselves with. The late Kashmiri American poet Agha Shahid Ali, in a large-scale act (or rather process) of translation, familiarized American poets and readers with the art of the ghazal, explaining its origins and spirit as well as its formal parameters.

Yet I would say that Urdu and the spirit of the ghazal are still not truly understood in the American literary consciousness. And how can they ever be? It is impossible work: to imbue centuries of history into the consciousness of someone who has not inherited it. Yet for the bilingual, bicultural poet’s work—and being!—to be understood, it must be done. And perhaps more crucially, the poet must do it to understand herself.

After Shahid formalized the ghazal, there were still many questions left, and room for further context amongst American poets. Zeest Hashmi’s book Ghazal Cosmopolitan (2017; reviewed in WLT) specifically focuses on this work. She continues the work in Comb, introducing the reader to many of the aspects and nuances of context necessary in understanding Urdu and Urdu-influenced poetry. She introduces unfamiliar readers to the legend of Khizr and Sikandar-e-Azam (Alexander the Great), who set out on a quest to find the aab-e-hayaat, the Water of Life, and thus attain immortality. She introduces readers to the Shahnameh, the Alf Layla (One Thousand and One Nights), to paris (fairies), and to jinn (djinns). In essence, she teaches readers to read from right to left.

In this way, Zeest Hashmi takes part in the eternal project of re-creating the forms that come together to create the consciousness of Urdu literature—its images, stories, lyricism, rhythm, and musicality. Poets who have inherited both English and Urdu poetic traditions are a particular breed; Urdu is alive in our poetry. The poet Kazim Ali once remarked that a lot of poets who share an Urdu literary tradition use a diction that sounds like Urdu. It is something my own ear can detect as well—perhaps it is the structure of our sentences, perhaps the rhythm, perhaps imagery, or perhaps it is more intangible. Whatever it may be, we are constructing our own home in American poetics, our own shahr-e-jaanaan.

Zeest Hashmi takes part in the eternal project of re-creating the forms that come together to create the consciousness of Urdu literature.

In this, we are also engaged in a quest to “rescue” Urdu—a word Zeest Hashmi used during one of our conversations. We are struggling to save Urdu from the clenches of imperialism and Western hegemony, a phenomenon that has the power to undo countless centuries of history and render our origins insignificant. This is to say, we are trying to preserve ourselves against the dominance of the English tongue.

*

On dominance: Zeest Hashmi teaches us about Rudabeh, the indirect inspiration for the Brothers Grimm’s Rapunzel. The original legend is from the Shahnameh, composed in the eleventh century by the Persian poet Firdowsi. In a short essay titled “Rope of Hair,” Zeest Hashmi writes:

In a legend, Rudabeh, the dark-haired princess of Kabul, lets her hair down like a rope for prinze Zal to climb up to her tower. She has eyes “like the narcissus and lashes that draw their blackness from the raven’s wing . . . about her silvern shoulders two musky black tresses curl, encircling them with their ends as though they were links in a chain.”

I couple this with a verse by nineteenth-century poet Mirza Ghalib:

آہ کو چاہئے اک عمر اثر ہوتے تک

کون جیتا ہے تری زلف کے سر ہوتے تک

A sigh requires a lifetime to take effect;

who will live until your curls are conquered?

To conquer a beloved’s curls is to untangle her complexities, and in doing so, the lover will have attained the deepest secret of the universe. But for Zeest Hashmi, it is the secret to the self.

For her, this secret lies in the Silk Road, that network of ancient trade routes which connected civilizations and empires. In this web of connection, this tangle of cultures, this exchange of spices, ideas, and language, she finds clues to her own origins:

I hunger for the spontaneous theater that a bazaar is—in the rising and falling rhythms of bargaining, banter, vendor songs, the strategic, pleasing arrangement of goods, the feasts of colors and aromas, there is an underlying confluence of art and trade, a tension between spirit, form, purpose, and value, much like the making of a poem. (“A Silk Road Bazaar”)

The Silk Road is a metaphor for the threads that intertwine to create the fabric of our existence. It is a reminder that all of us occur at the intersection of many, many histories. But it is also more than a metaphor; its existence is a physical reminder of the way we are connected with one another.

Comb invites us to reflect on our own intricacies, and the roads that have come together to create us. Zeest Hashmi—whose takhallus, or pen name, is Zeest, life!—how alive her language, how each unraveling brings us back to the stardust of our creation! In these pages, each artifact and phenomenon is a remnant of the past, a manifestation of the present, and holds the future in its substance.

*

Zeest Hashmi and I found each other in the book fair after our panel. I spent the rest of the day with her and her sons, eating decadent waffles and making Wajid Ali Shah jokes. As evening fell, we serenaded the streets of Portland with “Dasht-e-tanhaa’ii” (Solitude’s Desert), a famous poem by Faiz, immortalized by Iqbal Bano. By the end of the conference, I understood: we had found home, after all, in one other.

As she and her sons drove me to my lodgings, Zeest Hashmi played “Ghar naari ganwari,” a poem by Amir Khusro, traditionally sung as a qawwali. When I looked over, I saw her younger son dancing to the music with such energy that I could not help but feel a strange happiness. It may have just been Farid Aayaz’s periodic—and infectious—exclamations of delight. Or perhaps it was a dawning that we were at a crossroads and that our traditions were gaining a new life here, even as we lament their vanishing.