Layli Long Soldier’s Whereas Interrogates and Subverts a National Apology to Native Americans

Layli Long Soldier’s Whereas (Graywolf, 2017), a poetry finalist for the 2017 National Book Awards, contends with the U.S. federal terminologies in relationship to Indigenous people and reinscribes that terminology back on itself. Her interrogation of government bureaucratese, the so-called National Apology, has similarities to Solmaz Sharif’s Look—another Graywolf Press poetry title—in that Sharif also uses phrases and terms from a government text, the Department of Defense Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms. That Long Soldier and Sharif can appropriate such dry, flavorless language with all the excitement of an income tax manual into wildly arresting and diverse poetics demonstrates immeasurable expertise and flair. This is subversion working at its most potent potential and brings to mind Audre Lorde—“for the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house”—but, clearly, with exceptions. For Long Soldier and Sharif, dismantling the master’s house means unpacking its uses of language and terms.

Dismantling the master’s house means unpacking its uses of language and terms.

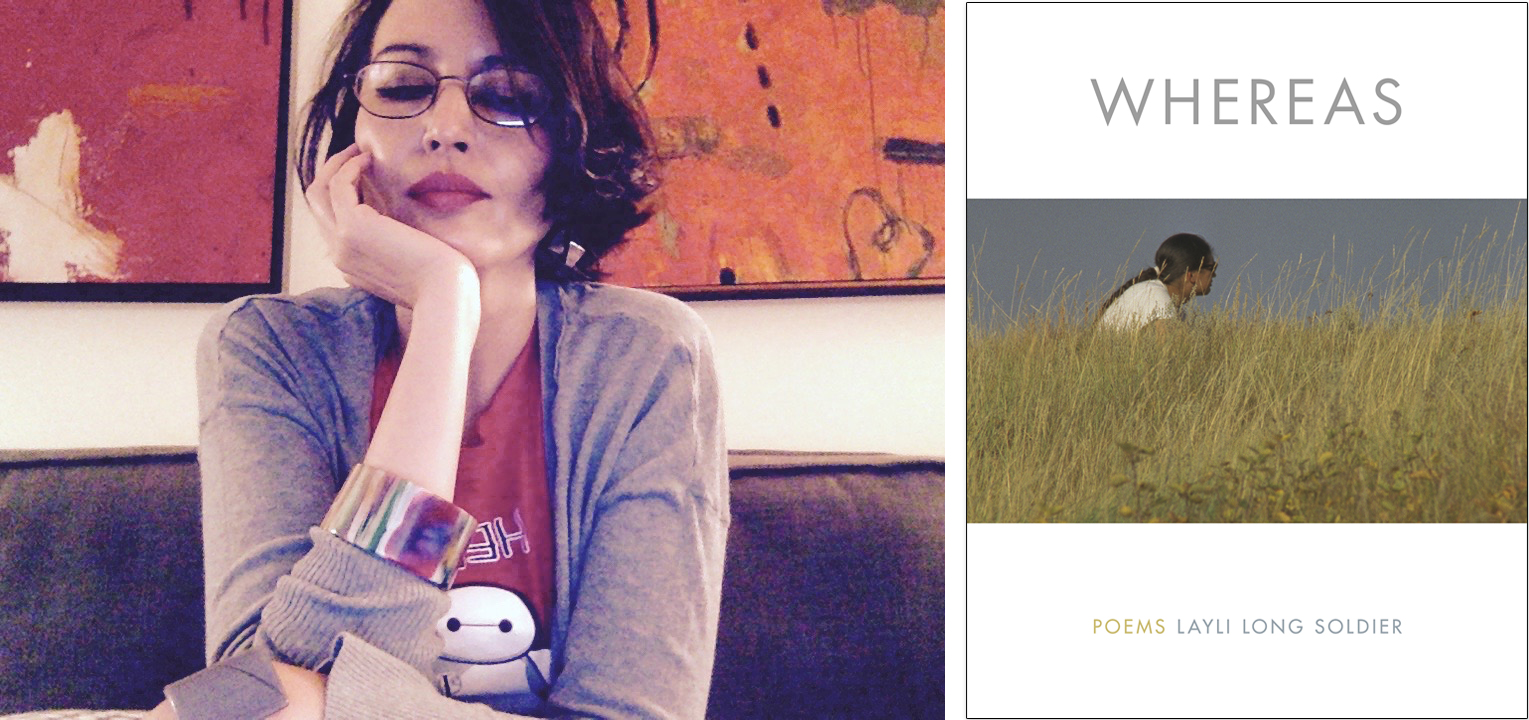

Whereas begins with an explication of the Lakota word for “mountain”—or “horn that comes from a shift in the river, throat to mouth”—and the Lakota word for “black.” This opening sequence, entitled Ȟe Sápa, contains five parts and serves as an appetizer for what is to follow, locating specifics and particularities between English and Lakota while establishing anchoring tones and themes throughout the collection. Yet Whereas actually begins with the image of grass—both in the cover art and as a kind of epigraph:

Now / make room in the mouth / for grassesgrassesgrasses

Flipping to the end of the book, the image is repeated: “. . . the grassesgrassesgrasses,” providing bookends. The reader learns from one of the most striking and audacious sections in Whereas entitled “38”—referencing the Dakota 38, the largest “legal” mass execution in U.S. history—about the possibilities behind the image of grass: “One trader named Andrew Myrick is famous for his refusal to provide credit to Dakota people by saying, ‘if they are hungry, let them eat grass.’” The speaker notes in the piece, “Yet, I started this piece because I was interested in writing about grasses.” Clearly, there are multiple meanings for grasses, and various amplitudes, but none as devastating and to the point as the following lines:

When settlers and traders were killed during the Sioux Uprising, one of the first to be executed by the Dakota was Andrew Myrick.

When Myrick’s body was found,

his mouth was stuffed with grass.

The title sequence to Whereas confronts the United States’ “official” apology to Native American people, the Congressional Resolution of Apology to Native Americans (2009). However, this resolution received little, if any, attention. There were no tribal people present to receive the apology, and it was not proclaimed or read aloud by President Obama before Congress; the text of the resolution included a disclaimer which asserted that nothing in the apology supports or settles any claim against the United States. So can this be considered an apology if it was not presented verbally, it there were no representatives present to receive it, and if it holds no consequences? Long Soldier writes:

My response is directed to the apology’s delivery, as well as the language, crafting, and arrangement of the written document. I am a citizen of the United States and an enrolled member of the Oglala Sioux Tribe, meaning I am a citizen of the Oglala Lakota Nation—and in this dual citizenship, I must work, I must eat, I must art, I must mother, I must friend, I must listen, I must observe, constantly I must live.

What follows are a series of responses to the Congressional Resolution of Apology to Native Americans using its very language and arrangement to resist, dissent, clarify, and “art.” While it would be recommended to study the actual document and use it as a map to assist in further readings of Whereas and to add contextual understanding, it is in no way necessary for the overall enjoyment and edifying sublimity of Long Soldier’s writing.

Distinctive, experimental, and conveying specific tribal aesthetics and inventiveness in both the Lakota language and English—an interesting marriage of metalanguage as well as an investigation of page space and variations on concrete poetry and reinscription—Whereas is a superb achievement, a must-have text for classrooms and libraries and for devotees of fine literature who advocate for human rights and social justice.

Moscow, Idaho