The Saga of Many Patient Foot Soldiers: Józef Wittlin’s Salt of the Earth

My association with the work of Józef Wittlin started when Professor Anna Frajlich invited me to write a paper about Wittlin’s association with France for her 1996 Józef Wittlin conference at Columbia University. I jumped at the chance to travel to Maisons-Laffitte, north of Paris, France, where the bulk of Wittlin’s correspondence with Jerzy Giedroyc was preserved. There, I began my acquaintance with Wittlin through his second, postwar literary career. At the conference, I met and was warmly welcomed by Elizabeth Wittlin Lipton, the writer’s daughter. Anyone who has met her will tell you that it is nearly impossible not to become her friend. Her energy and dedication are infectious. She introduced me to the unfinished odyssey of her father’s Sól ziemi. While revising my conference paper for publication in the conference’s proceedings,[i] I sought a French publisher for the novel. Noir sur Blanc was interested. My translation appeared in 2000, and it is still seen on the shelves of the Polish bookstore owned by the publishing conglomerate Libella on Boulevard St. Germain in Paris.[ii] The 1996 Columbia conference and my translation, which was the first French translation of the novel since the war years, began to take Wittlin out of his “literary purgatory.”

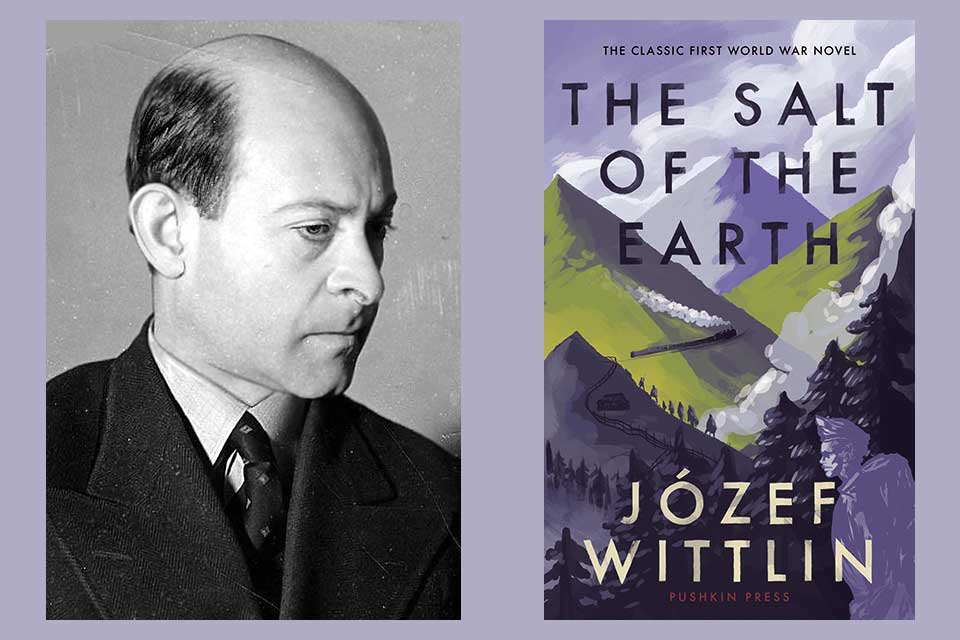

Józef Wittlin was born in 1896 in Lviv, where he grew up. After enrolling in the Polish Legion in August 1914, he joined the Austro-Hungarian army in 1916 with his friend Joseph Roth. His 1924 translation of Homer’s Odyssey was a classic. He had penned a volume of poems about the war and numerous essays. An indefatigable traveler, his Etapy (Travel notes), published in 1933, had made him well known in Poland. He was an active member of the Polish and European literary community, a friend of Franz Werfel and Hermann Kesten; the latter would help save the family during the dark days of 1940. On the eve of World War II, Wittlin’s blooming literary career was threatened by the rise of anti-Semitism.

Wittlin was an active member of the Polish and European literary community, a friend of Franz Werfel and Hermann Kesten; the latter would help save the family during the dark days of 1940.

When Wittlin’s first novel, Sól ziemi – Powieść o cierpliwym piechurze (The salt of the earth: The saga of the patient foot soldier) first appeared in Poland in 1935, it was awarded the “Wiadomości Literackie” (Literary news) prize in 1936 and the Zloty Wawrzyn (gold laurel wreath) from the Polish Academy of Literature in 1937. It was immediately translated into Czech, Hungarian, German, English, French, Iranian, Russian, and Swedish.[iii] The German translation by Izydor Berman, which could not be published in Germany, appeared in Amsterdam in 1937 to great acclaim. The French translation by Raymond Henry was first published in installments in Le Temps between December 1938 and May 1939; the book edition by Albin Michel followed in the summer of 1939. These prewar translations and honors testify to the international success enjoyed by Józef Wittlin in the prewar years. Topping it all, Sól ziemi was nominated for the 1939 Nobel Prize. But Wittlin had announced it as the first volume of a trilogy. The second volume was to be titled A Healthy Death and the third A Hole in the Sky. The Stockholm committee decided to wait until the trilogy was complete. Preparing for this monumental work, Wittlin had done extensive research between 1925 and 1935 in Austrian and French military archives. The first volume had required ten years of work. It was unlikely that he could write the next two volumes quickly.

The outbreak of World War II changed Wittlin’s life dramatically. After Nazi troops invaded Poland on September 1, 1939, Wittlin, who was residing in France with a trunk full of documents and drafts, desperately tried to extract his wife and daughter from occupied Warsaw. After the family was reunited in March 1940 in Biarritz, they were forced to leave France. Wittlin’s life was in danger after the fall of France in June 1940: his name was on the Nazis’ blacklist, and German troops, storming the Editions Albin Michel, were destroying all copies of Le Sel de la Terre. While the family was about to embark a British boat, a soldier threw overboard Wittlin’s precious trunk, which sank to the bottom of the St. Jean-de-Luz harbor. Once on American soil, his career seemed to resume auspiciously. The English translation of Pauline de Chary, first published in England in 1940, was published by Sheridan Press in New York in 1941, earning Wittlin a 1943 prize from the American Academy of Arts & Letters and the National Institute of Arts & Letters.[iv] A Hebrew translation appeared in Tel Aviv in 1943, a Croat translation in Zagreb in 1943, and a Spanish translation in Buenos Aires in 1945.

While the family was about to embark a British boat, a soldier threw overboard Wittlin’s precious trunk, which sank to the bottom of the St. Jean-de-Luz harbor.

The second phase of Wittlin’s literary career was shaped by the Cold War. As an émigré writer, Wittlin could not hope to be published in Poland. He was now associated with Columbia University in New York City, which was a haven for Eastern European intellectuals during and after the war. He read literary essays for Radio Free Europe and remained close to Mieczysław Grydzewski, who continued to publish “Wiadomości Literackie” in London. And he cultivated ties with Jerzy Giedroyc, the founder of the Instytut Literacki who would become his main publisher. His two major postwar works, Mój Lwów (My Lviv) and Orfeusz w piekle XX wieku (Orpheus in the hell of the twentieth century) were indeed published in the “Kultura” collection of the Instytut Literacki, in 1946 and 1963, respectively. By the mid-1960s, Wittlin was working with Jerzy Giedroyc on the publication of his integral works by the Instytut Literacki.

Wittlin never found the strength to reconstitute the meticulous research he had assembled before the war, even though he received repeated encouragements from Mieczysław Grydzewski and Jerzy Giedroyc, who deemed Sól ziemi the best literary work of interwar Poland. Two prewar friends worked on his behalf in France: Bernard Champigneulle interceded with Albin Michel, which still held the rights to the French edition of all three volumes of the trilogy; and Jacques Allier repeatedly urged him to complete the trilogy. In 1954 the original Polish publisher, Rój, who had resumed his activities in the United States, published a new Polish edition of Sól ziemi. In the mid-1960s, Wittlin resumed research in France and Switzerland. In 1968 Fischer Verlag, which still owns exclusive worldwide translation and publication rights for the novel, republished Das Salz der Erde in Izidor Berman’s translation. In 1970 Stackpole published a third edition of Pauline de Chary’s English translation.

Despite these encouraging signs, however, Wittlin only produced the first twenty-five pages of A Healthy Death. They were published in the pages of the “Kultura” journal in 1972. I translated them, and they are included with my postscript to the 2000 Noir sur Blanc volume. They reveal the poignancy of an unfinished work, that empty center of Wittlin’s creativity which constantly gnawed at him and around which he continued to write in the two genres that were best suited to his temperament, namely essays and travel notes. Neither his death in 1976 nor the continuing Cold War put an end to the career of Sól ziemi, however. A posthumous edition appeared in Warsaw in 1979, and the critical, definitive edition of the novel was published by Ossolineum in 1991. In 2014 a paperback edition of the novel was issued in Poland. An Italian translation appeared in 2014. Fischer Verlag continues to republish Das Salz der Erde with regularity, in the translation of Izidor Berman, with revised introductions.

Securing the legacy of Wittlin’s literary work required the work of many patient foot soldiers. The most important of these was and is his daughter, Elizabeth Wittlin Lipton. The English translation of Wittlin’s major postwar work, Mój Lwów, in 2017, was an important moment.[v] But the greatest success to date is the revival of interest in Sól ziemi. The novel received a new English edition in time for the centenary of the end of World War I. Translated by Patrick John Corness and published by Pushkin Press in Britain, this new edition of The Salt of the Earth is lively, faithful, and sensitive to the cultural nuances that make the novel such a rich tapestry of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy prior to World War I. Spanish and Dutch translations are in progress.

This new Pushkin Press edition of The Salt of the Earth is lively, faithful, and sensitive to the cultural nuances that make the novel such a rich tapestry of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy prior to World War I.

It is interesting to me that several translations of Sól ziemi have been done through or with the help of a third language. Not knowing Polish, Raymond Henry worked from the German translation of Izidor Berman. When I started translating Sól ziemi into French in 1999, I had before me the excellent translations of Izidor Berman and Raymond Henry, which Elizabeth Wittlin Lipton had procured. Having the same text written in three languages within five years of each other helped me to delve more fully into the cultural ambience of the early part of the twentieth century. Being the first to translate Sól ziemi into French from the Polish text, however, I paid great attention to the cadences, images, and sounds of Wittlin’s prose. More recently, I received a request in early 2019 from a Dutch editor for a copy of my translation for the Dutch translator. Wittlin, who was a perfectionist, might have approved of this method.

A pacifist and a humanist, Wittlin sought to describe in Sól ziemi the bewilderment of a simple foot soldier confronted with the outbreak of World War I. After a prologue describing the panic unleashed on the people by the declaration of war on Serbia by the Austro-Hungarian monarchy on July 28, 1914, Wittlin locates the action in the Hofburg Palace where Emperor Franz-Joseph signed the mobilization document. The first chapter of the novel mirrors this contrast between street chaos and imperial palace solemnity. In Hutsul country, deep in Galicia, between Bukovina and Hungary, a railroad man named “of unknown father” Piotr Niewiadomski tends to the small station of Topory-Czernielica. The night is disturbed by a loud and blinding lone last peace train whose passage hints at the disruptions and devastations soon to occur in the form of mobilization, armaments, and Red Cross trains.

The novel gives a rare glimpse into the coming of war on the Eastern Front and shows its impact on men who do not speak the same language and are thrown together into a war that will rend their identity and their homeland. This Proustian-type novel takes almost three hundred pages to narrate Piotr Niewiadomski’s trip from Topory-Czernielica to the military depot where he is to be outfitted and trained. With the delicate brush of a Douanier Rousseau, Wittlin paints the discoveries and astonishments of his main character, narrates his encounters with other soldiers and with the military authorities, and shares his fears and dreams about a sinking Eden. Part nostalgia for a vanished world, part painstaking witness of ancient traditions, and part historical reconstruction of the last days of peace in the summer of 1914, the novel anticipates the alienation of returning veterans and the deep wounds that gashed interwar society in central Europe.

University of Tennessee at Martin

Sample Translations of the Opening Paragraph of the Novel

Polish Original (1935)[vi]

W głuche zakątki huculskiej ziemi, pachnące miętą w letne wieczory, w senne wioski, przylepione do cichych połonin, gdzie pasterze grają na długich trombitach – wdziera się kolej żelazna. Ona jedna łączy ze światem te ustronia, zabite od niego deskami. Ona rzuca w ciemną noc barwne światła semaforów i gwałci ciszę, i gwałci dziewiczość wielkiego nocnego spokoju. Wrzaskiem oświetlonych wagonów rozdziera błonę mroku, przeciągłym gwizdem budzi ze snu zające i uśpioną łudzką ciekawość. Jak olbrzymia żelazna drabina, przybita gwoździami do kamienistej ziemi – z nieskończoności w nieskończoność ciągną się na drewnianych progach czarne, połyskliwe szyny. Biały domki stacyjne, ujęte w żywopłoty, ogródki, altany i klomby z kolorowymi, szklanymi kulami na ubielonych drążkach, listne mostki żelazne nad strumykami i gęsto rozsiane budki dróżników zadają kłam pozorom, jakoby na tej ziemi diabeł mówił: dobranoc!

Izidor Berman (1937)[vii]

In die tauben Winkel der huzulischen Erde, die an Sommerabenden nach Minze duftet, in verträumte Dörfer, die an stillen Almen liegen, wo die Hirten lange Holzflöten blasen, dringt die Eisenbahn. Sie allein verbindet diese entlegenen Gebiete mit der Welt. Sir wirft in die dunkle Nacht die bunten Lichter der Signale und vergewaltigt die Stille und Jungfräulichkeit des grossen nächtlichen Friedens. Mit dem Getöse beleuchteter Waggons zerreisst sie den Schleier des Nebels, weckt mit langgedehntem Pfiff die Hasen und die eingeschläferte menschliche Neugier. Wie eine ungeheure schimmernde Leiter, auf felsigen Boden gelegt, laufen schwarze Schienen auf hölzernen Schwellen von Unendlichkeit zu Unendlichkeit. Weisse Stationhäuschen, von Hecken umzäunt, kleine Gärten, Lauben und Blumenrabatten mit farbigen Glaskugeln auf weiss angestrichenen Stökken, unzählige eiserne Brücklein über Bäche gespannt und Wärterhäuschen, dicht nebeneinandergereiht, strafen die Mär Lüge, hier sage der Teufel dem Beelzebub gute Nacht.

Raymond Henry (1939)[viii]

Dans un coin perdu de ce district de Hutsulie où la terre fleure la menthe les soirs d’été, dans les villages endormis le long de calmes pâturages où les bergers tirent, de longues flûtes de bois, des sons mélodieux, le chemin de fer a pénétré. Lui seul relie au monde ces régions qui en sont séparées comme par une cloison de planches. Il projette dans la nuit sombre les lumières versicolores des signaux; il viole le silence et la pureté de la grande paix nocturne. Le fracas des freins illuminés déchire les nuages de brume; les longs sifflements des locomotives réveillent en sursaut et les lièvres, et les curiosités humaines assoupies. Semblables à une monstrueuse échelle d’acier clouée au sol rocailleux par des traverses de bois, les rails, brillant d’un éclat sombre, déroulent d’infini en infini leur double ruban. De petites gares blanches entourées de haies vives, de petits jardins, de petits bosquets, de petits massifs de fleurs, ornés au centre de boules de verre de couleur sur des trépieds peints en blanc, d’innombrables poteaux métalliques enjambant des ruisseaux, des maisonnettes de gardes-barrières alignées à de brefs intervalles, tout cela semble contredire au caractère de cette contrée perdue au diable vauvert.

Alice-Catherine Carls (2000)[ix]

La voie ferrée entaille le sol jusqu’au fin fond de la terre hutsule qui embaume la menthe les soirs d’été, jusque dans les villages endormis accolés aux silencieux alpages où les bergers sonnent leurs trompes. Elle seule relie au monde ces endroits perdus, condamnés par des planches clouées à en être séparés. Elle jette dans la nuit noire les lumières multicolores de ses sémaphores et viole le silence, et viole la pureté du grand calme nocturne. Le vacarme de ses wagons éclairés déchire le voile du soir, son sifflement prolongé réveille les lièvres et la curiosité ensommeillée des humains. Tels une géante échelle en fer assujettie à la terre pierreuse par des clous, les rails noirs et luisants filent d’infini en infini sur leurs traverses de bois. Les gares blanches serties de haies vives, de jardinets, de charmilles et de parterres fleuris ornés de boule de verre coloré posées sur des tiges blanchies, les nombreux petits ponts en fer franchissant les ruisseaux et les postes de garde-barrière échelonnés tout au long du parcours, font mentir les apparences, comme si le diable disait à cette terre: “Bonne nuit!”

Patrick John Corness (2018)[x]

Into distant, forgotten corners of the Hutsul country – filled with the aroma of mint on summer evenings, sleepy villages nestling in quiet pastures where shepherds play their long wooden horns – comes the intruding railway. It is the only connection these godforsaken parts have with the outside world. It pierces the night’s darkness with the coloured lights of its signals, violating the silence, violating the immaculacy of the profound night-time peacefulness. The din of its illuminated carriages rends the membrane of darkness. A long-drawn-out whistle blast awakens hares from their slumber and arouses people’s drowsy curiosity. Like a great iron ladder nailed down onto the stony ground, shiny black rails on wooden sleepers stretch from one infinity towards another. Little white station buildings surrounded by hedges, vegetable plots, gazebos and flower-beds with coloured glass orbs on white-painted sticks, numerous little iron bridges crossing streams and countless small signal boxes give the lie to any impression that this part of the country was totally God-forsaken.

[i] Alice-Catherine Carls, “Józef Wittlin’s Passage through France,” in Between Lvov, New York, and Ulysses’ Ithaca: Józef Wittlin, Poet, Essayist, Novelist, edited by Anna Frajlich, 157–75 (Nicolaus Copernicus University Press, 2001).

[ii] Józef Wittlin, Le Sel de la terre, translated by Alice-Catherine Carls (Noir sur Blanc, 2000).

[iii] Zoya Yurieff Joseph Wittlin (Twayne, 1973), 166.

[iv] Ewa Wiegandt, “Wojna, pokój i dusza poety,” introduction to Sól ziemi, by Józef Wittlin (Zakład Narodowy imienia Ossolinskich no. 278, 1991), lxxx.

[v] Józef Wittlin, City of Lions, translated by Philippe Sands (Pushkin Press, 2017 ).

[vi] Wittlin, Sól ziemi, 29.

[vii] Józef Wittlin, Das Salz der Erde (Suhrkamp Taschenbuch 3169, 2000).

[viii] Józef Wittlin, “Prologue (suite): Le Sel de la terre,” Feuilleton du Temps, 27 décembre 1938, page 4.

[ix] Wittlin, Le Sel de la terre, 35.

[x] Józef Wittlin, The Salt of the Earth, translated by Patrick John Corness (Pushkin Press, 2018), 43.