Any Wonder Left

Cleaning out her deceased father’s home in Dublin, a woman reluctantly accepts help from an unsettling stranger.

My two sisters and I work throughout the day, clearing out our parents’ home. The easiest room to tackle is the kitchen, there great satisfaction to be had in throwing away the useless and expired: food, condiments, flyers, paid bills, and inkless pens. The hardest space to brave is Dad’s bedroom. Here, especially, my sisters and I argue over what should stay or go, right down to his medications, faded bookie receipts, and dusty shoes. In the end we throw away almost everything except photographs, Granddad’s blackthorn walking stick that Dad treasured, and the newspaper comic strips that Dad collected over decades.

My two sisters and I work throughout the day, clearing out our parents’ home. The easiest room to tackle is the kitchen, there great satisfaction to be had in throwing away the useless and expired: food, condiments, flyers, paid bills, and inkless pens. The hardest space to brave is Dad’s bedroom. Here, especially, my sisters and I argue over what should stay or go, right down to his medications, faded bookie receipts, and dusty shoes. In the end we throw away almost everything except photographs, Granddad’s blackthorn walking stick that Dad treasured, and the newspaper comic strips that Dad collected over decades.

By mid-afternoon, fourteen fat plastic rubbish bags line both sides of our parents’ driveway. The three bags on the right will go to the charity shop, and the eleven on the left to the city dump. A neighbor, Mrs. Reilly, barrels through the front gate and stands scowling at the bags, her disapproval as obvious as her drooping breasts. “Yis didn’t start into all that already?” she says.

Dad is dead two weeks.

“Had to be done sometime,” I sing out. She looks at me like my ruthless head has turned three hundred and sixty degrees. She knows I staged a similar swift erasure of our mother’s belongings last spring, just a few weeks after she died. My smile remains defiant. Mrs. Reilly’s expression shifts to a kind of pity, as if she’s remembered I’m not only an adult orphan now, but also a young widow.

“I’ll let yis get back to it,” she says, unable to keep the lingering disdain out of her voice. She turns on her heel, her ankles pale and plump as halibut.

My sisters and I return inside, getting away from the black bags sweating in the afternoon heat. It’s as if the sun has gone rogue, defying winter. The idea that nature is staging its own rebellion is strangely comforting, given my own pushback against everything that’s happened.

* * *

In the kitchen, over copious cups of tea, my sisters and I reminisce about our parents, childhood, and the neighbors, issuing bursts of laughter and sometimes sniffling. My sisters swipe at their red-rimmed eyes with bunched, flaking tissues. Beyond the French doors, birds swoop in and out of the back garden, pecking uselessly at the red metal feeder. The empty birdseed sack is in a black bag out front. I imagine it was one of the last things Dad did, refilling the feeder. I make a note to pick up more seeds.

In the nearest corner of the garden, the two gray, ring-necked doves remain perched on a bottom branch of the apple tree. Dad bought the young tree in Aldi a few years back. I’d told him it would never grow, and most certainly never bear fruit. Mum, shaking her gray-blond head, sounded a small laugh. “That man. He might as well have flushed the five euro down the toilet.”

When the tree grew and its first green apple appeared, Dad rubbed his hands together with delight. “Didn’t I tell yis.”

He further gloated over the two collared doves stationed on the lower branches of the tree, insisting they were the same pair that had visited his garden every day for years.

“How can you know?” I reasoned. “They could be any of thousands of doves.”

“They’re the same two,” he said, his voice thick with tenderness, reverence.

I pour more tea. Of the four chairs at the table, it’s no accident that I’m sitting in one of the two neutral seats. Tina sits in Mum’s chair and Isabel sits in Dad’s. When we sell the house, they will likely want to keep this table and chairs and most of everything else that remains. They’re welcome to the lot. I don’t want any such reminders. Mementos are nothing more than evidence of the missing.

We discuss how to get Dad’s belongings to the dump. The haul is much bigger than we expected and will require at least three trips in Tina’s car. “I don’t even know where the dump is,” she says. At thirty-two, and with those downturned lips and large brown eyes that always look damp, she still holds hard to her status as the baby of the family.

“It’s not called the dump anymore. It’s some sanitized name now, a civic center or something,” Isabel says. She’s the most attractive of the three of us, with her long chestnut hair, smooth, sallow skin, and jutting cheekbones. At thirty-five, she still cannot drive and refuses to learn—too afraid of losing control of the vehicle, and of not being in control of other drivers. I doubt, though, she knows the kind of powerlessness that makes your lungs feel trapped inside plastic, or the terror that makes your heart feel like it will detonate.

Tina volunteers their husbands to transport the bags. Both men are at home, minding their respective children. “It’s too late today, but I can check to see if the dump, or whatever it’s called now, is open tomorrow.”

“No husbands needed, and no point in dragging this out,” I say with an edge. “I’ll take care of it.”

Tina and Isabel exchange a look that conveys both sympathy and irritation. At thirty-eight, I am the eldest and have always played the part of the capable, bossy sister much too well.

“You don’t even have a car,” Tina says. Her cheeks flare red. “Oh God, sorry. That was a stupid thing to say.”

Brendan’s and my car was smashed in the collision, a write-off. “I’m going to get it sorted. I’ll be back in a bit.”

Ignoring their protests and apologies, I walk out of the kitchen, and the murmuring house.

* * *

The sign that had stood on the neighborhood green for months, advertising a handyman, is gone. I scan my surroundings, disbelieving, angry. Some unseen power keeps messing with me.

A tall, lean man walks a lively King Charles along the tarmac pathway circling the green. I approach, thinking he’s likely a regular. Up close, he’s not as old as I’d first thought, maybe in his late fifties. There’s still something handsome about his rugged face and pale blue eyes. He confirms I’m not mistaken and that there was a sign for a handyman. He looks about us, also mystified by its disappearance. We shouldn’t feel so surprised. The world over, things—people—are here one moment and gone the next.

“Is it a big job you need doing?” he asks.

I tell him about the bags of my dead father’s belongings. “I’d really like rid of them today.”

He shakes his head, his hair dyed the brown of a bird’s nest. “Good luck finding someone to do that run for you at this hour.”

The base of my throat buzzes. “Thanks anyway,” I say, turning to leave. The King Charles jumps up on my legs, his sharp nails scratching the back of my knee. No one since Brendan has touched such an intimate part of me, or made me feel much of anything.

The man tugs on the dog’s leash. “No, Frankie.”

Some stuff sounds made up. Like how Mum, Dad, and Brendan died in the same year.

Dad’s name was Frank. I almost tell the stranger, but don’t. Some stuff sounds made up. Like how Mum, Dad, and Brendan died in the same year.

“I have a friend with a truck, and I think he’d do it for you nice and handy. Let me see if he’s around. How much can I say you’ll give him?”

“How about fifty euro?” I say, hoping it’s in the realm of a fair price.

He looks dubious. “He’ll have to pay dump fees, remember.”

“Eighty, then?”

“That might work.” He walks toward the middle of the green, his phone to his ear, and quickly returns. “Sorry, no answer.” He taps the side of the phone to his thin lips. A mustache would give him more of a mouth. “I can make this happen. Leave it with me.”

We walk off the green together and onto the street, me thanking him repeatedly. He types Dad’s address and my mobile number into his phone.

“You’re a star.” I extend my hand. “Nicola.”

We shake, his touch warm. “Eamon.” He promises to recruit a couple of lads with a van from Cabra and says he’ll escort them to Dad’s house himself. “We can be there in fifteen, twenty minutes.”

My gratitude jumps to suspicion. How can he drum up lads with a van in Cabra of all places, and at such short notice? My pulse quickens, as though a wind has picked up inside me, driving my blood faster. “I’m putting you to too much trouble. Please don’t worry about it. I’ll figure something else out.”

“It’s no bother, and trust me, I only ever do what I want.” The bite to his voice and chill in his glacier-blue eyes make me believe him.

* * *

Eamon pulls up outside our parents’ house in a gray BMW. A white Ford Transit trails him, three lads filling the front passenger seat. I rush outside and close the front door behind me, not wanting them to see into the house, and maybe whet their appetite for more that they can take. My sisters watch from the bottom of the living room window, both crouched on the carpet, peeping out like kids. They are horrified that I’ve given a questionable stranger my phone number and our dead parents’ address. Worse, I’m entrusting him with the disposal of Dad’s belongings.

The three lads jump from the van with alarming purpose and quick-march up the driveway. They are dark-haired, stocky, and already have a certain savagery etched into their young faces. I point at the long row of bags on the left, smiling hard. “Just take everything on this side, please.” My voice smacks of fake, fearful cheer.

Eamon appears next to me. “Good news. They agreed to do the job for fifty euro.”

“Thanks, but we said eighty. Let’s stick to that.” I pull the four folded twenties from my jeans pocket, anxious not to piss off the youngfellas and risk them returning, looking for their full due.

I hand over Dad’s money. During our clearing blitz, my sisters and I found over three hundred euro that he’d hidden inside various ornaments and a fat sock deep in his nightstand drawer, saving the money for never.

“Fair is fair,” I add automatically, echoing something Dad often said and which I now disbelieve more than ever. There is no such thing as fairness—only luck, bad luck, and worse luck.

Eamon adds the notes to his thick money clip.

In a matter of minutes, the lads have all eleven bags thrown into the back of the van. I thank them yet again, breaking records for the depths of insincerity. They climb into the vehicle and look out from the front seat, their craggy faces blank. I shiver, realizing they are waiting for Eamon to signal their next move.

My need to supervise the sendoff turns urgent. Not least because these lads might fire the bags into a ditch, saving themselves the spin across town and pocketing the entire eighty euro. “Would it be all right if I followed them to the dump?” I blurt, thinking to borrow Tina’s car.

Eamon nods, his slight lips pursed. “I don’t see why not. I can take you.”

“No,” I say too fast, that wind again whipping the blood around my veins. His brow knits, and I rush to add, “You’ve done more than enough already.”

“I insist.” The clouded look leaves him. His blue eyes glitter with mischief. “Besides, those lads drive like maniacs at the best of times. They’re a nightmare altogether when they’re being followed.”

“It’s too much,” I say, a nervous tremble in my voice.

He smiles with just a hint of cruelty. “If I didn’t know better, I’d say you were scared.” He lifts his chin toward the trio in the van. “Is it them?” He looks right into my eyes. “Or is it me?”

Despite how much I’m shaking, I do my best to stride toward his car with a spine of oak, and sit into the shiny vehicle with as much grace as possible. A voice in my head demands to know what I think I’m doing. I imagine my sisters are wondering the same, and half expect them to charge from the house. Eamon slides behind the driver’s wheel, chuckling. “All right then.”

My phone pings, a worried text from Tina. I type back reassurances.

As we drive, Eamon tells me he’s seventy years old. I can’t hide my surprise. “You look great.”

“I can assure you it’s not from easy living.” He tells me he made and lost fortunes, and served eight years in Mountjoy for tax evasion. “The only thing those bastards in CAB could pin on me.” It takes me a second to register that he’s talking about the Criminal Assets Bureau. Just before Christmas, he continues, a masked gunman assassinated his brother-in-law on the street in broad daylight, a gangland revenge murder. “At least I’m still above ground.”

“Wow,” I say, hearing how ridiculous I am. I consider jumping from the car the next time we stop at a traffic light.

“Prison gave me lots of time to think. I read all sorts of books, philosophy mostly. I’m not the man I was. I’d never again do the things I did.”

The silence stretches. I try not to think about the things he might have done.

The silence stretches. I try not to think about the things he might have done.

“You?” he asks. “What’s your story?”

“Well, nothing like yours,” I say, not intending to be funny, but he laughs, firing from deep in his stomach.

He wants to know if I’m married, if I have kids, and where I live. I aim for vague but not antagonizing—you don’t not answer his kind—and tell him no, no, and on the other side of town.

“Nothing wrong with a quiet life,” he says.

There’s so much I could say to that, but don’t. Like how my life has taken to screaming.

* * *

We arrive at the dump, now called a civic amenity site. It couldn’t be further from my memories of the place. As a girl, I’d gone here with Dad when we got rid of our rusted bathtub and the broken washing machine. The stink had hit us long before the mountains of rot and ruin came into view, and while I expected the skittering rats, I could never have prepared myself for their sheer number, like black, moving hills. I hadn’t expected to see so much color amid the dark debris, either—blots of reds, pinks, yellows, and blues.

The amenity site is surrounded by metal railing topped with barbed wire. Inside stands a village of gray, corrugated warehouses splashed with the mill of yellow-vested workers. Eamon shifts on the driver’s seat, his expression knotty. He’s perhaps having flashbacks to Mountjoy Prison, and could take his trauma out on me. I should never have come here.

At the site’s entrance, a man in a white hardhat and orange vest grips a clipboard and speaks with the lads in the van. Eamon’s car idles behind them, and I watch with growing alarm as the exchange turns heated. The driver rushes from the van and plods wide-legged toward Eamon, like he’s fresh from bare horseback riding.

“They want to know what’s in the fucking bags. Everything has to be divided into all different kinds of shit, recycling and wha’ not,” he says.

My mood plunges. It would take an age to sort everything in those bags into their respective piles. “It’s just rubbish,” I say, protesting, pleading. A horrible feeling rushes me. That’s the bulk of my dad I’m talking about.

“Leave it to me,” Eamon says, exiting the car. He talks with the gatekeeper, their heads close together, and slips him money. As he walks back to the car, the gatekeeper gives the driver directions, his arm outstretched. The van peels away. Eamon returns to the car, and we roll forward.

“I’ll pay you back,” I say, not wanting to be any deeper in his debt.

“Don’t worry about it,” he says.

I receive another text from Tina, demanding an update. I thumb a rushed reply, at dump all well, and hope that is indeed the case.

The BMW snakes along the main path and past the metal warehouses, columns of compressed, multicolored waste, and mounds of plastic recycling. The computer screens are piled high and wide in a rectangular block like a huge, many-faced robot. We reach the landfill, where there’s another gatekeeper, this man younger, blockier. He waves the van and Eamon through.

While Eamon and I remain inside his car, the three lads pull the bags of Dad’s belongings from the back of the Transit and toss them onto the heaps of mangled waste like they’re nothing.

“That’s it, don’t look away,” Eamon says. It’s as if he knows I’m fighting the urge. A chill scissors my back. It was Brendan who discarded Mum’s belongings, sparing Dad, my sisters, and me from the task. Six months later, while he was driving home from work, a car going in the wrong direction on the motorway crashed into him head-on.

In the days after his funeral, I stripped our home, getting rid of everything from the bottles in the drinks cabinet to the last stick of furniture, emptying the place of him, and him and me.

Family and friends despaired. Would you not wait? You might regret it. You shouldn’t do anything so soon, let alone this. Is it not a terrible waste? I ignored them and isolated myself, a hedgehog curled into a spiky ball.

Much more than my favorite ornaments, furniture, and kitchenware—more than our photographs, the jewelry Brendan had given me, and the ticket stubs we’d saved from every concert we’d attended together—it was his phone with his voicemail recording that proved the hardest to part with. After selling and donating everything I could, I hired a laborer to haul the plastic bags of belongings away. Sometimes, seized with regret, I want to shriek, thinking of all those bits of Brendan—of us—scattered without a heart sloshing with love looking on.

Tina texts again. She and Isabel are heading to the charity shop with the remaining three bags, and then home to their families. She orders me to text her as soon as I get back from the dump so we know ur safe. I send a thumbs up. Seagulls wheel over the landfill, a screaming plague. The vast, tangled sea of waste comes at me in an enormous wave and fastens my breath like a stake. The place would claw at any wonder left in your head.

* * *

Eamon drives me back to my parents’ house, the winter dark already dropping. We arrive shortly after five o’clock, and the sight of the cleared driveway sends me into a fresh panic. I don’t want to enter the empty house alone. I consider asking Eamon to drive me home instead, to the shell of what was, but I can’t risk him knowing where I live. I should bolt, but I feel heavy on the passenger seat, the effort to get up and out too much. I tell Eamon about the collared doves that Dad insisted were the same two birds in his garden every day, for years.

“Plenty of stranger things are true,” he says.

I reach for the door handle, rattled again. “Thanks a million.”

“You’re welcome. God is in the deeds, not the details.”

Before I can stop myself, I crack a laugh. “Are you saying you’re God?”

He smirks. “Let’s leave it at God-like.”

“I’m starting to think He’s another delusion.”

Eamon sad-smiles. “Careful. Wars have started over people saying less.”

“True.” I haul myself out of the car, wondering again at his crimes.

I feel him watch me as I walk away. At last he starts the engine, and I can breathe easier, but it’s like my windpipe still has kinks. In my periphery, the gray BMW streaks past like a shadow.

* * *

I sit in the deepening dark at Mum and Dad’s kitchen table, the starless night pushing against the French doors. The rest of the world looks empty. It hits me again that soon the house will be sold. Gone. With my share of the proceeds, and those from the home I shared with Brendan, I’ll press ahead with buying a new place and starting fresh. I check the back of my knee, still stinging from the dog’s nails. Three thin, red scratches look back at me, so slight it seems impossible they can hurt. I half expect Eamon to reappear, and remain braced for a knock on the front door that doesn’t happen.

A disturbing disappointment squats on my chest. My eyelids flutter, fighting tears. I ache to be held in strong arms, to rest my head on a broad shoulder, to nuzzle in the drift of Paco Rabanne. I check myself. I’ve no such notions regarding Eamon, of course, but the strange encounter loosened bolted-down feelings.

I’ve long hated how the media and entertainment romanticize these men.

It’s unnerving. Eamon’s an ex-con and gangland boss who’s likely a killer, and I’ve long hated how the media and entertainment romanticize these men. Dublin and beyond is rife with them destroying each other, along with innocent bystanders and victims of mistaken identity. What a waste—throwing themselves and others away. Thoughts of the discarded, too many gone too soon, threaten to tear me open.

Outside, the motion light is triggered, illuminating the back garden and the two ring-necked doves settling on the apple tree. I inch closer. Through the glass door, I try to study the birds’ tiny heads and plump little bodies, looking for any distinctive markings. I ease open the French doors and creep outside, hoping I can get close enough before the pair fly away. I don’t. I stand in the garden, watching the birds disappear into the dark. Maybe they were Dad’s to believe in, and not mine. Maybe my proof of return, of the amazing that might yet remain, lies elsewhere. The clearing, emptying, I’d made plenty of space for it, hadn’t I?

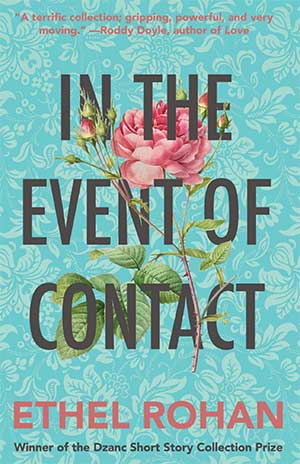

San Francisco

Editorial note: From In the Event of Contact (Dzanc Books), Rohan’s latest collection of short fiction available May 18, 2021. In the Event of Contact won the Dzanc Books Short Story Collection Prize.