Elegy of a River Shaman (an excerpt)

Translators’ Note

Acclaimed in China, Fang Qi has published two works: Elegy of a River Shaman and The Ivory Bed of the Princess. A long-term researcher of myths and shamanism, she devoted her life to examining, cataloging, and preserving the folklore of and archaeological excavations from the middle and upper Yangzi Valley. The following is an excerpt from the prelude to her novel Elegy of a River Shaman (forthcoming from Merwin Asia in August 2016), a multigenerational epic of panoramic scope and generous spirit that follows the loves and losses, the triumph and despair of the Li family in the rugged, remote gorges along the Yangzi River. The rhythmic songs of shaman Xia Qifa, the novel’s tragic hero—a doomed figure as China ineluctably marches toward modernity—serve as the primal backbeat for this compelling story, a cautionary tale that is at once timely and timeless, culture-specific and universal, and resonant with political, ecological, and cultural immediacy.

Acclaimed in China, Fang Qi has published two works: Elegy of a River Shaman and The Ivory Bed of the Princess. A long-term researcher of myths and shamanism, she devoted her life to examining, cataloging, and preserving the folklore of and archaeological excavations from the middle and upper Yangzi Valley. The following is an excerpt from the prelude to her novel Elegy of a River Shaman (forthcoming from Merwin Asia in August 2016), a multigenerational epic of panoramic scope and generous spirit that follows the loves and losses, the triumph and despair of the Li family in the rugged, remote gorges along the Yangzi River. The rhythmic songs of shaman Xia Qifa, the novel’s tragic hero—a doomed figure as China ineluctably marches toward modernity—serve as the primal backbeat for this compelling story, a cautionary tale that is at once timely and timeless, culture-specific and universal, and resonant with political, ecological, and cultural immediacy.

* * *

Once again, a banner rose over the village. The shaman Xia Qifa thrust his palms aloft, his fingers contorted into a mudra, taking the form of a crouching tiger. Completing the motion, he blew the oxhorn forcefully. His chants pierced the dense clouds and mists shrouding the Yangzi River—that meandering creature that carved its course through gorges and flowed past docks, exiting at Kuimen, the Gate of the Thunderous One-Footed Dragon—and echoed in the halls of the seventy-two temples along its banks:

O, celestial White Tiger,

Gliding across the firmament with your long loping stride,

Covering endless stretches of road.

O gorger on flesh and hide,

Forests splinter and earth sunders in your terrible wake.

For as long as the elders could recall, the village had been controlled by invisible hands, the evidence of which was that the flag, without wind at dead noon, now moved spontaneously, twisting and fluttering. Faces soaked in perspiration, villagers knelt on the scorched earth, watching as the tassels on the fringe of the banner first swayed, then wound their way into knots as the banner rose.

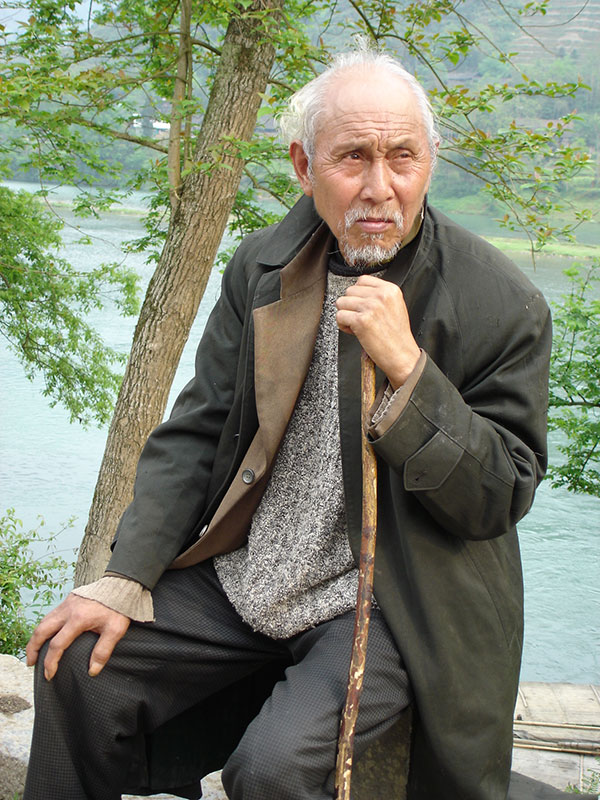

Presiding over this grand rite was Xia Qifa, a shaman revered above all other men in these parts. To welcome his tiger ancestor, Xia Qifa, crowned with a feathered crest, gyrated as he tinkled his bell, his skirts sweeping the dusty ground.

Five years earlier, when the reaches of the Yangzi River were in the throes of a similar drought, county official Pock-faced Zhang, pistol in hand, stood in Xia Qifa’s yard, and said politely, “I’ve heard you possess great magical powers. You have three days to make the Dragon King bring rain. If you succeed, you’ll be rewarded generously. If you fail, you’ll be shot!” With these words, Zhang fired the pistol into a straw effigy of the wicked dragon, making smoke issue from the parched stalks. As cumbersome darkness receded and the first sunrays broke forth like so many unleashed arrows, Xia Qifa, thirty-seventh in the family line of timas, [1] had led his disciples to fashion an earthen altar. To the blowing of horns and beating of drums, the tima donned his bird-shaped crest and red skirt, like a phoenix readied for battle. Under the unfurled banner of their tiger ancestor, he led a procession of hundreds on a march to Baizhang Valley, to a dark cave of unfathomable depth, wherein dwelled the Dragon King’s third son, a volatile princeling who capriciously swallowed rivers and roiled oceans. When the mercurial dragon tired of this sport, he disgorged the waters into the cave bottom creating an underground river that flowed all the way to the Eastern Sea.

At the mouth of the cave, gazing amidst the rising incense smoke at the whirling currents, an anxious Xia Qifa burned sacrificial paper. Beside him, disciples fired guns into the maw of the cave; the reports giving off a terrifying echo.

Generation after generation of Xia shamans, sometimes in triumph and sometimes in defeat, waged battles against the dragon prince.

It was the tima’s duty to subdue the wicked dragon. Once upon a time, a figure clad in golden armor appeared to one of his Xia ancestors in a dream, announcing, “I, the Immortal Tiger, have come to transmit to you the mystical arts of the tima.” Thus, the ancestors of Xia family were taught to dispel devils and defeat dragons. Generation after generation of Xia shamans, sometimes in triumph and sometimes in defeat, waged battles against the dragon prince. These victories and failures were faithfully recorded in local annals: so it was known that the first Xia ancestor had perished in mortal combat. In this fiercest of battles, as passed down in local lore, two straw sandals outside the cave rose from the ground, attacking one another like fighting cocks! The disciple assigned to beat the drum was so dumbfounded that he forgot his duty. Just at that instant the tima, exhausted yet victorious, emerged from the cave dragging the wicked dragon by the beast’s horns. The sudden cessation of the drumbeat enabled the crafty creature to shake free and surge back into the cave. Then, with a terrible explosion, a mighty gust of thick smoke and flame erupted from the mouth of the cave, incinerating the first ancestor, leaving behind only a hero’s name.

During that unforgettable summer of 1929, Xia Qifa had approached the vast mouth of the cave, hiking his worn skirt up to his knees; like his first ancestor he removed his straw sandals. Grasping a charm in one hand and holding aloft his sword in the other, his face a mask of otherworldly isolation, he waded through the churning torrent into the cavernous darkness. People waited outside as the cave exhaled a violent wind. They heard an ear-splitting cacophony, like the clamor of two armies of ten thousand engaged in battle. At the height of the fury, the nervous throng faintly glimpsed a huge tiger paw within the cave. Knowing this to be the supernatural form of Xia Qifa, some dared hope he might overcome his foe. The battle raged on, then, lo and behold, a heavy mass of cloud floated across the baking firmament. The skies sundered, bringing a sudden thunderstorm. O splendid tima! The ox-skin drums of the shaman’s disciples below kept time with the thunder booming above, and the world was saturated in a salubrious downpour. Garments tattered beyond recognition but wearing an expression of complete serenity, Xia Qifa strode out of the cave. Naturally, this hard-fought victory over the dragon brought him great fame.

And yet five years later, the calamity-bringing dragon sought to swallow the river once again, prompting Xia Qifa to don his shamans’ robes and straw rain poncho to confront the wicked creature a second time. Swaying like a serpent, flitting like a bird, bowl of water in hand, he moved forward with purpose and force.

Floating in the war-stricken wilderness, strains of an ancient ode hung in the air:

O, Great King Immortal Tiger,

Humbly I follow your path

As you rage ever forward

If you walk the path to drought, I follow

If you find a road to water, I follow

In the aftermath of the great flood four millennia ago, Bodhisattva-King Yu the Great had used the same strange swaying gait to beg the intercession of spirits to help vanquish the dragon and quell the deluge. So now under the yellow banner of his ancestors, Xia Qifa, thirty-seventh tima in the illustrious Xia line, gracefully staggered, following the cryptic divine paces, shaking his bronze bell to summon the Immortal Tiger. On this day, however, the banner hung motionless.

Sweat coursing down, Xia Qifa realized this was the most formidable test he had faced. He looked closer at the pottery bowl in one hand, carefully scrutinizing the water. Gloomily, the befuddled shaman murmured, “The hidden river . . .” Why, with the same movements and paces, the same prayers and spells, could he not call forth that set of hands to release the winds and unfurl the flag? After repeatedly inquiring the trigrams from the Book of Changes, the shaman darkly pronounced, “The dragon prince has claimed that swallowing the river is not a crime. He’s filed a lawsuit in the Celestial Court against the Immortal Tiger.” Puzzled and weary, the pale tima choked out the following words, “Matters in the Heavenly Court can drag on for decades—a day up in the heavens is a year down in earth. We mortals can’t wait for our Tiger ancestor to resolve the case. We need to move now and find a new place to settle. Shoulder your carrying poles and gather your belongings . . .” Though the Tribe of the Tiger had moved countless times, this was the first time that the men and women of the village had moved.

Those who trusted the tima gathered all they could carry; those who couldn’t bear to pull up stakes remained to face whatever came. Cloth parcels fastened to their waists, a hungry exodus followed the shaman.

Those who trusted the tima gathered all they could carry; those who couldn’t bear to pull up stakes remained to face whatever came. Cloth parcels fastened to their waists, a hungry exodus followed the shaman. Rifle slung over his shoulder and straw sandals on his feet, Li Diezhu led his family, following the refugees eastward along the dried-out bed of the Guandu River. Xia Qifa, ancestral Tiger staff in hand, the mystical instruments of generations of shamans bundled in a rucksack, moved solemnly ahead of the miserable villagers. A melancholy chant slowly flowed from his lips—

Father-in-law takes to the road,

Mother-in-law takes to the road.

The sun rises, off we go,

The suns sets, we rest our weary feet.

Walking trails where the deer run

Passing places where the monkeys jump

Climbing cliffs where the mountain men walk

Wandering shores where the crabs crawl

In 1934, 3,936 years after Yu the Great quelled the flood dragon and came to rule China, the region was so severely drought-stricken that the land burned, crops died, and wells dried. The sun hung in the sky, a relentless blazing fireball that left people squinting and dizzy. Observing bamboo trigrams to seek guidance of the spirits, the last tima of the Three Gorges region of Yangzi River worried day and night over the starving refugees in his charge. Guided by birdsongs and coloration of river shrimp, the weary, tattered band moved toward the sunrise. To the accompaniment of the homespun chants from the village they had left behind, they clambered over Nanmuya Hill, passing through Azure Dragon Hamlet, Shi Family Embankment and other villages. So they drifted, dancing in the breeze like a handful of windsown seeds, borne on a faraway journey to they knew not where.

Translation from the Chinese

By N. Harry Rothschild & Meng Fanjun

[1] Tima is the term that the “Tribe of the Tiger,” as the author of the novel calls the Tujia people, use for their shamans.