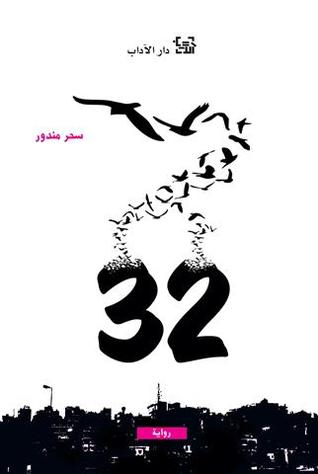

Hayat (an excerpt from 32)

A best-seller at the 2010 Arab Book Fair in Beirut, 32 follows the life of a young woman in her thirties, her four female friends, and a Sri Lankan domestic worker. The book sheds light on life in Lebanon from the perspective of women, giving voice to her generation in the aftermath of the civil war. This excerpt is about Hayat, a character that is introduced halfway through the novel as a childhood friend of Boudour, the narrator. It is only later in the novel, though, that Hayat’s true, surprising identity is revealed.

A best-seller at the 2010 Arab Book Fair in Beirut, 32 follows the life of a young woman in her thirties, her four female friends, and a Sri Lankan domestic worker. The book sheds light on life in Lebanon from the perspective of women, giving voice to her generation in the aftermath of the civil war. This excerpt is about Hayat, a character that is introduced halfway through the novel as a childhood friend of Boudour, the narrator. It is only later in the novel, though, that Hayat’s true, surprising identity is revealed.

My friend, my neighbor growing up, is the same age as me.

Her name: Hayat. Arabic for life.

I’m serious; her name means life. She was named after her aunt who was born sick and died a child.

Her fiancé, Qrunful, died a martyr.

A martyr?

No.

Hayat says he’s not a martyr. She insists that he was a victim and refuses to call him anything else. “He didn’t choose to die,” she says. And politics meant nothing to him. “He loved me, and that’s it. He’s not a martyr, he was my fiancé, and he is a victim.” That’s what she yelled on the third day of grieving when a visiting official arrived and proclaimed Qrunful a martyr in front of her and her family. That day everyone treated her like she had a breakdown. Only Qrunful’s mother stood up for Hayat and asked everyone to leave her alone and to stop telling her to go rest in the bedroom. Only Qrunful’s mother stood by her side and asked the visiting official, forcefully but politely, to kindly and quietly get out.

So, Qrunful left this world a victim of a car bomb that targeted a Lebanese minister of Parliament.

And Hayat left for Paris.

That was three years ago.

Before the engagement and the death, Hayat was a little gloomy, and in that we were a lot alike. But she was determined to devour to the fullest the life she was named for. She insisted on trying everything, especially the sexual and political. She changed mood and political views as much as she changed her hair color, that is, with every season. She loved Qrunful because they met during one of her experiments. He loved her because she didn’t judge his actions but shared them—the drinking and sexing and fighting strangers, even the speeding, and never politics. When she got pregnant with his child, they decided to get married. Not as a result of social pressure, not at all. She had decided not to have an abortion, declared her desire to get married, and proposed to him. He told her then that he had wanted to propose to her first but was worried that she’d yell at him for being “so old-fashioned!”

She laughed her heart out when he told her that and asked him, “Do you always base your decisions on how you think I’m going to react?” Qrunful got upset with her insinuation that he was weak-willed, so she hugged him in front of me and said, “I never imagined myself married. But you, because you’re so mindful of my feelings and thoughts, will be my one and only husband. After I divorce you, I’ll stick to casual sex.” We laughed.

He died a month later.

And she got an abortion.

She got an abortion and left for Paris.

She had a lot of sex there, but it was revenge sex. Once, I called her to wish her a happy thirtieth birthday and to tease her about her old age, of course, and we got onto the topic of sex “at this age,” and she laughed and said, “I have sex to justify my screaming in the middle of the night.” I didn’t believe her then because I was confident that she loved sex for the sake of sex, as one loves art for its own sake. But I now know that her sexual relations after Qrunful’s death didn’t come from a healthy place.

Her body ached.

Everything inside her ached.

Translation from the Arabic

By Nicole Fares