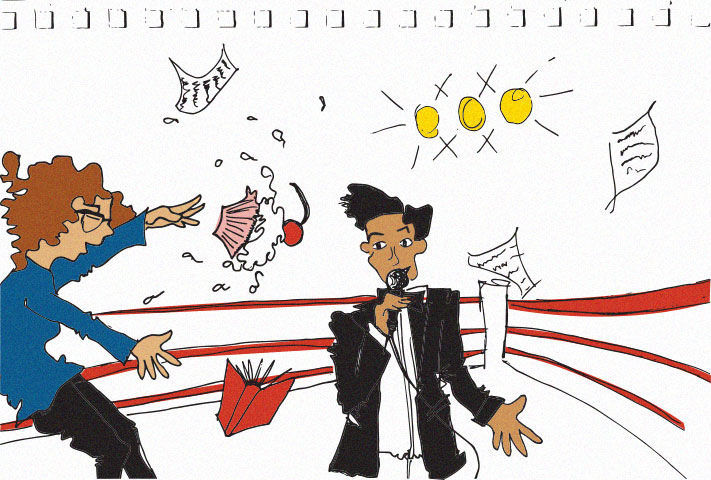

Fiction by Way of Cupcake-throwing: Amelia Gray on the Literary Death Match

On March 13 fiction star Amelia Gray will perform in Boston at the seven-year anniversary of the raucous phenomenon known as the Literary Death Match, a monthly competition between four writers with three judges, two rounds, and one often-insane finale. According to its home website, a match “marries the literary and performative aspects of Def Poetry Jam, rapier-witted quips of American Idol’s judging (without any meanness), and the ridiculousness and hilarity of Double Dare.

Prior to last year’s release of her first novel, Threats, Amelia Gray was already a fiction writer to be reckoned with, publishing two works of short fiction in 2009 and 2010 with Chicago-based press Featherproof and impressive avant-garde press FC2. But publishers aren’t the only means by which she distributes her work: besides shouting portions of Threats from a moped, Gray also circulates her fiction at these matches.

If you’re like the editors of WLT, you might find yourself wondering what it is like to read (read: holler) portions of unpublished work from a stage in front of an audience, judges, and fellow (often famous) contemporary fiction writers. Below you’ll find Gray’s thoughts not only on the experience of an LDM, but also on how her participation in these loud literary forums might have an effect on her authorship and work.

Sara Wilson: How did you become involved in LDMs? Were you contacted, or did you sign yourself up for one of these literary duels?

Amelia Gray: They asked me a few years back for the Texas Book Festival in Austin. It was the first LDM in Austin, the second in Texas, and kind of an unproven concept, so of course I was into it immediately. I read the threats from Threats while holding a bag full of quarters.

SW: What are some general impressions you’ve had about the experience of reading in an LDM? Correct me if I’m wrong, but I’ve read that you’ve participated in at least nine of these matches.

What are they like? Does the experience change based on either the authors or judges you compete with?

AG: Every LDM is different. I like how much the four readers can vary in terms of genre and subject. There’s the kind of show that ends with people throwing cupcakes, and the kind that ends with everyone going home to write. I’ve been to a lot more shows than I’ve been an active part of, since Todd Zuniga runs them here out of Los Angeles.

SW: To what extent is the competition affected by the content you read onstage?

AG: I’d say the audience has a lot to do with the outcome. A reader who is bold with whatever they’ve brought is more likely to get the crowd on their side. A piece that’s more technically perfect can easily lose if the writer doesn’t kind of sell it. And then sometimes the crowd just doesn’t want to hear something funny, or something serious, or fiction, or true. At the end of the day, it’s really supposed to be fun, not a serious competition—the last round is a randomizer—so I would hope nobody goes into it with a deadly serious strategy.

SW: What goes into preparation for a Literary Death Match, exactly?

AG: From the judge/performer side, one just has to show up. Readers should time themselves to make sure they’re going under seven minutes because going over is illegal and rude as hell, man. The real work in preparation comes from Zuniga, who is plotting and inviting and tweet-blasting and doing promotion for weeks prior.

SW: Does the audience have a role in the proceedings? Has it ever interfered when you’ve been a performer or judge?

AG: The audience is usually very chill and positive. I co-hosted once and saw one of the judges make a joke that had good intentions and fell very flat in a bad way, and the crowd at that point wasn’t afraid to make their displeasure known immediately. I like that it’s a lively crowd—it’s another thing that makes it less of an ordinary reading. It’s lively; it moves at a clip.

SW: One of the most arresting aspects of LDMs seems to be that authors and readers/audiences experience the literature together in real time. Whether or not you imagine an “ideal” reader when you’re at your desk writing, will your experience with the audience at LDMs influence the way you write in the future?

AG: I try hard not to think of my audience at all when I’m writing. Some things I turn out just end up being better for a performance reading, while others don’t work at all. It’s tough but not impossible to do dialogue out loud. The pieces I end up reading at LDM and elsewhere tend to involve just a few lines of dialogue, if any.

SW: In your first LDM, you made it to the final round. Who were you up against? What form did your finale take?

AG: I was reading against the excellent Kyle Beachy in the first round. Jason Sheehan and Jeff Martin went next, and then Jason and I went up against each other in a Texas trivia contest, where I had the advantage because he’s from Philadelphia. It was cool to meet those guys—I already knew Kyle from Chicago. I hope to get up to Tulsa soon to read with Jeff again.

SW: It seems that the finales of these competitions require a fair amount of improv skills: how bawdy do you have to get on stage?

AG: I’m not generally a bawdy lass and I’ve done all right. Some of them are unfortunately more physically skill-based—such as lobbing footballs at pictures of authors, or the cupcake-throwing—or knowledge-based, such as local trivia or spelling contests or music knowledge. I’m not very good on the spot; I’ve lost more than I’ve won.

SW: Ultimately, what does an LDM really come down to: egg-book-bowling skills or literary prowess?

AG: Bowling, for sure.

SW: Who have been some of your most memorable judges? What tack did their commentary take?

AG: I love the comedian judges—the best ones have a quick mind for the material they’re given, and they can make of a couple of good, quick jokes without being mean about it. It’s fun to watch and aspire to. I really liked Joe Wengert, Jason Mantzoukas, Tig Notaro.

SW: Would you agree that the Literary Death Match is a platform that reveals literature’s connection and relevance to the social world? Having participated both as judge and participant, you have had the opportunity to see LDMs at work on a number of levels. From these multiple perspectives, what does the LDM do for and to literature?

AG: I do like the connection and relevance the LDM offers. Todd asks the crowd if anyone is new to the show and a ton of people respond to that. It’s not a stagnant audience—the same kind of people who come to the same shows—it’s a crowd that’s there to see this judge or that reader and then they learn about seven or eight more people. Even if I’m involved in the show, I leave knowing about a couple of people I never would have met or read with otherwise. It’s a great thing.

SW: Much of your work seems to alternate between dichotomies: reality and the world of dreams, life and death, darkly humorous and playfully serious themes. You’ve been compared to the likes of Barthelme because your fiction is often read to be both whimsical and powerful. Is there a correlation between these characteristics found in your work and the ways that LDMs play out? Do you see a connection between the surrealism often pointed to in your work (I’m thinking of Threats in particular) and what occurs in a Death Match?

AG: Well, all of it contains multitudes, sure. Also, I feel comfortable bringing even the most surreal work on stage at the LDM, so there’s a home for strange thought. I think Barthelme would have killed it at the Death Match, assuming he knew his Texas trivia.

SW: For the match on March 13, will you be reading from Threats? Who are you competing against, and what might be your biggest challenge in this match?

AG: I probably won’t be reading from any book—I prefer going to newer stuff since it’s more fun to read and surely more fun to hear. The biggest challenge is going to be avoiding the impulse to wrap Tony Hoagland up in a big scary hug.