Holding Death in Our First Breath: A Conversation with Naja Marie Aidt

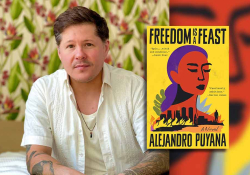

Naja Marie Aidt is the author of twelve collections of poetry, a novel, and three short-story collections, including Baboon, which won the 2008 Nordic Council Literature Prize. Her most recent memoir, When Death Takes Something from You Give It Back (2019), is a sweeping, spare, and masterful account of the first few years after her twenty-five-year-old son, Carl, died in a tragic accident. Of Aidt’s most recent work, Valeria Luiselli has written: “There is no one quite like Naja Marie Aidt. She’s comparable only to things like sequoias, whale-song, desert thunderstorms, or wolves. The depth of her emotional world and the diaphanous often brutal clarity with which she understands the human soul beckon us to pause, breathe, think.” In the following interview, conducted via email, we talked about the violence and rage of early grief, the loss of Carl and its aftermath, the limits of expressing profound emotion through language, and how to map time in prose when any sense of chronology or linearity in life is shattered. Aidt was born in Greenland and raised in Copenhagen. Coffee House Press just published the English-language version of her memoir, translated by Denise Newman, whose earlier translation of Aidt’s short-fiction collection, Baboon, won the 2015 PEN Translation Prize. The following is an excerpt from our exchange.

Kathryn Savage: I was struck by your powerful laying bare of the role of rage in grief. So often described as a heaviness, I’ve personally experienced grief as a kind of out-of-the-boundaries-of-time rage, a shattering. This feeling has something to do with time and timelessness collapsing simultaneously in the body, I think. Death as finality, and, quoting poet Larry Levis: “The last thing my father did for me / Was map a way: he died, & so / Made death possible.” You write, after your son Carl’s tragic death, that Now that you can no longer be in chronological time, neither can we. You quote Roubaud: “In your loss of time I found all of myself included.” I wonder if you would be so generous as to speak to the relationship you find between time and timelessness in grief and, also, the role of rage in grieving?

Naja Marie Aidt: Well, when you experience a very sudden shock and get extremely traumatized, within minutes it feels like you fall out of the world somehow, fall out of time. It feels like time stops, and at the same time is so painful, every minute is pure torture, and as everyone else is still in normal time it is a very lonely feeling. I remember it felt like being excluded from everything I would consider normal before Carl’s death; nothing was normal. Roubaud describes it very accurately, I think. As a gesture for the dead person, body and mind automatically follow the dead into this timelessness. The loss of time; it just happens. In a way, I find it beautiful, but to live through this timelessness is tough. No wonder people feel that they are going mad when they experience this. Time, and the trust in time, seems to be crucial for humans. I think you are right—it is a bodily experience. The rage, the timelessness, and most importantly, maybe, the time it takes to understand that this has happened—this is true, my child is dead, how could it happen, etc.—all these questions torturing the mind is the first important process to go through.

I remember waking up in the morning and for a second I was unaware of what happened, and then had to face the new reality once again, try to understand it. Much later, the heaviness came. The exhaustion, the depression. The rage would come in waves, being a desperate way to try to cope. There is the deep despair, and there is rage. Sometimes, I just screamed. Sometimes I hated every person I saw in the street, smiling and laughing, carefree and enjoying themselves. Sometimes, I couldn’t cry anymore, and the crying would then turn into anger. The anger is necessary, I think. Anger is powerful, and I remember thinking that if I could get that angry and hate life so much, there was still hope—that I hadn’t lost my power completely.

Anger is powerful, and I remember thinking that if I could get that angry and hate life so much, there was still hope—that I hadn’t lost my power completely.

Savage: The Epic of Gilgamesh, more than four thousand years old, is woven throughout your work. You write about Gilgamesh’s inability to accept the death of his beloved friend, Enkidu. After Enkidu’s death, Gilgamesh wanders in grief carrying the body of his friend for six days. With Enkidu’s body he wanders, thinking: “If my grief is violent enough, perhaps he will come back to life again.” Violence and rage seem so central to grief (maybe, also, to notions of time and timelessness in grieving), but these emotional registers are often absent from elegies, I feel, or if present, they are aestheticized and anesthetized. I wonder if you might agree? If so, how do you understand this?

Aidt: Rage is not considered a “nice” feeling. Rage can easily lead to violence—we don’t want that, for good reasons, and I think it is a taboo when it comes to grief. Rage is not pretty, it is not poetic, not beautiful. It is harsh, grim, and ugly, so maybe it is left out of elegies for that reason, but it might also be because when you write about your loved one who has died you want it to be pretty as a way of honoring the dead person, or it might be because the elegy is not written in the state of raw grief. Rage belongs to raw and early grief, I think, so maybe writers forget the physical feeling of this intense and destructive anger when some years have passed. Or, they might just be ashamed of it.

I love that it is so well described in the Gilgamesh epic. Rereading it while grieving was just so powerful for me. I felt included by people walking on this earth more than four thousand years ago. I felt included in humanity again, let back in, so to speak. I was not alone. Loss and grief have forever been the hardest thing for us to deal with, and still are. It is just so overwhelming and mysterious, but it is something we share, and yes, I understand why Gilgamesh hopes that his anger will bring his friend back to life. Almost as if the noise and drama from the rage would wake up the dead!

When the anger passed and turned into heaviness—and depression, in a way, was worse, because in that heaviness came the clarity that Carl could not come back to us—the acceptance of his death started with that heaviness, the fight was over, in a way, and I had no other options than to give up. We cannot fight death no matter how hard we try, but we still try. That is resilience, and resilience is power, which again means we are able to be alive even in our darkest moments.

We cannot fight death no matter how hard we try, but we still try.

Savage: You’ve written a deeply moving and important book about the worst thing that can happen as a parent, the tragic death of your twenty-five-year-old son. After Carl’s sudden death you began writing Carl’s Book, and there’s an aching passage I’d like to quote:

I think about my dead child; his time and his life are folded into me. I gave birth to him. I must hold his death. I will continue to fight like a lioness for him. No one should wrong him. No one should forget him. Not as long as I am alive. I still protect him, I know him just as well as I know my living children.

It’s a physical feeling:

He is inside me.

He is inside my body.

I bear his spirit in my body.

I am a mother, and I read this passage and thought, Yes, it can be no other way than that. I’m interested in thinking about your book not as an act of imagination or creation but an act of holding Carl’s spirit in your body. Does this book feel more physical, if that makes any sense, than your earlier works of poetry and fiction? How did it feel to write this book, if that isn’t too invasive of a question?

Aidt: Yes, it felt much more physical. It was a very physical act to write this book, it was so hard, so painful, but also the only thing I could do. I am a writer; that’s how I understand and explore life. Writing this book, it sometimes felt like the writing was my sword. Also, it was a constructive way to “spend time with Carl,” if that makes any sense. I could spend a couple of hours a day dwelling deep into his being, his spirit, his way, and that felt like doing something meaningful in a state of total meaningless. I think I am a writer that always writes very physically. Baboon is probably a good example of that, but this time nothing was as it used to be. The feeling of losing my language—and that language offered no rescue—was very overwhelming since language has always been what I turned to in both happy and difficult times. Now I felt language was empty and powerless, almost ridiculous, and I did not care for a long time—that was actually part of my anger. I felt like: “Go to hell, language, you have betrayed me!” so rage was also what drove me to write, to fight language and death at the same time and to write for Carl, to hold him with me even though he was gone.

The process of accepting death and learning how to hold and turn to the dead loved one, to find a way to still be with him, this is crucial, I think, in order to survive and live a good life after such tragedy. Almost like reinventing the dead person so that you can “meet” him on a different level. I still treasure that, and I spend time turning to him, talking to him, remembering him, asking him for guidance and help, sometimes. So yes, I carry him in my body and it feels right. Almost as if he had withdrawn from the world, crawling back into his mother’s womb where he came from in the first place. It’s hard for me to remember quite how I wrote this book. Much of that time has disappeared into shadows now. I was hardly myself. Nothing was familiar. It’s hard to describe the writing process. I see it as a desperate act in order to survive both as a writer, a mother, and a human being, but also, as a way to share my experience with readers, with fellow humans. It was a way for me to give something back.

It’s hard to describe the writing process. I see it as a desperate act in order to survive both as a writer, a mother, and a human being.

Savage: Turning more squarely toward craft, you articulate that most writing on “raw grief and lamentation is fragmentary. It’s chaotic, not artistic.” You write, “To comprehend the incomprehensible is not linguistic.” This presents a challenge for the writer. Expertly organized and woven intricately, I am interested in how your book came to find its final form. The fragments are skillfully and movingly placed. Did it come out in this form, so to speak, or was your organization of the book a different revision process than the earlier drafting of it?

Aidt: It actually came out in this form, more or less. I did little editing. At first, I would write a few words down on bus tickets, napkins, or in a notebook, and then at some point I typed this writing in a file on my laptop. That was the first step. One day, I started writing about the evening when I got the phone call that Carl had been in a deadly accident, and that turned out to be a gift for the form. All of a sudden there was a form, and I began to see the texts as a tree with branches and leaves. Poems and texts would surround the “tree trunk.” The tree trunk was the very detailed italicized text about what I remembered from those first few days after the accident happened until Carl was declared brain-dead in the hospital. I could not write this text in one go. I had to do it little by little, take breaks, so to speak, and I think it turned out well to do it that way because the readers are able to take breaks as well. It made it bearable for me to write the book but also makes it bearable to read it, I think.

Savage: Yes, I loved the italicized sections in your book, concerned with that single narrative and interrupted by poems, passages from Inger Christensen, Gilgamesh, Denise Riley, Walt Whitman. Every time the italicized section returns there’s a quality of repeating and then proceeding through the chronological events after Carl’s deadly accident. You describe time in a state of raw grief as circular, not chronological. (“Now that you can no longer be in chronological time, neither can we.”) This sentiment reminded me of an essay I love, “Woven,” by Lidia Yuknavitch. Yuknavitch writes, “Every story I have ever told has a kind of breach to it, I think. You could say that my writing isn’t quite right. That all the beginnings have endings in them.” A circle is a form that collapses chronological time, beginnings and endings. Did this form arrive after you began writing, or was it your intention to give the narrative a circular architecture from the start?

Aidt: I did not know exactly what I was doing at first, but at some point, yes, it was clear to me that this form was able to hold and describe both time and timelessness at the same time, and it then became clear to me that it had to be a circular form. It took me a while to realize that the book had to end with Carl’s death. It starts with the night of the accident, and then his birth, so it had to end with his death, but in between life and death, this form offered a freedom to jump in time constantly, going back to the different phases of Carl’s life and the different phases of losing him, grieving, in one big mix. It felt like a very organic and elastic form that actually was able to give form to something that felt so very confusing and formless. I totally agree with Lidia Yuknavitch! It goes for stories, but it goes for life itself, too. When we are born we hold our death in us from our first breath. It is there, waiting. I find that beautiful. We are just nature, like the flowers and the trees, connected to everything living on the planet. We have our time, we bloom and then we die.

When we are born we hold our death in us from our first breath. It is there, waiting. I find that beautiful.

Savage: In Anne Boyer’s 2019 New Yorker personal essay, “What Cancer Takes Away,” Boyer writes, “The boundaries of our bodies break. Everything we were supposed to keep inside us now seems to fall out.” Boyer is talking about chemotherapy and the devastating experiences people undergo during cancer treatments. I was reminded of Boyer’s essay in the section where you write about the erasure of the “I,” the self, in grief:

there is no I anymore, only we

Nothing is real. Language is emptied of meaning.

I keep returning to the idea that bodies and language are all we have but are profoundly limiting and limited in the face of death. This alienates us from each other and unites us, collapses the “I” to “we,” and the boundaries of our bodies break. Do you think there is something at once deeply singular and also boundaryless and simultaneous about grief?

Aidt: Yes. Everyone grieves in her own way, and in her own right, and it can feel very lonesome, but at the same time, grief is something we experience together. The collapse of the “I” is the weirdest and most disturbing experience. The total loss of identity and the feeling that this “I” cannot contain or process what is happening to it. There is no way. It has to collapse in its former form. So while you are in a state of deep shock after losing a loved one, you lose yourself at the same time. It is very frightening. Rebuilding your “I” in a way that can contain and live with this new experience takes time. I remember, maybe three years after Carl’s death, that I recognized parts of my old personality again. That was joyful. My “I” was restoring, it was now able to bloom more, but it was not the same. There is before and there is after. The transformation or transition is profound, just like it is for the person who dies. Again, we follow our dead loved one’s transition just as we mirror their loss of time.

On the other hand, it was very powerful to melt into my grieving family and my grieving friends, and Carl’s friends as well, we were like one huge organism, paralyzed but together, connected so tight that now it is hard to describe what it actually felt like then. A silent togetherness where language had lost all meaning. There were no other ways to be than to dwell in this togetherness, there was no choice, it happened automatically, and I think it saved us. When I look at grief now, after having met so many grieving people while touring with Carl’s book, I see how simultaneous grief is. If feels special to every single person, but it is just as simultaneous as I felt it while reading Gilgamesh.

This has made me more aware of compassion and love on a broader scale. I think Carl’s death has taught me an important lesson about compassion on a very physical level, and I am truly grateful for that. That way, this experience of losing Carl has broadened my understanding of life, death, and the human body and soul. Carl has taught me true solidarity and how we are connected in a very deep and moving way. He was always talking about solidarity and togetherness when he was alive, but I don’t think I understood fully what he meant on this very deep level until his death taught me the hard way. I often think of that. That Carl, by dying, maybe made me a better person, and maybe a better writer, too.

August 2019

Editorial note: Michelle Johnson interviewed Denise Newman about translating Aidt for the WLT blog in 2014: “Revelation through Restraint in Naja Marie Aidt’s Writing.” Bailey Hoffner’s review of When Death Takes Something from You Give It Back will headline the review section in the Autumn 2019 issue of WLT.