Interconnected Ecologies: A Conversation with Kathryn Savage

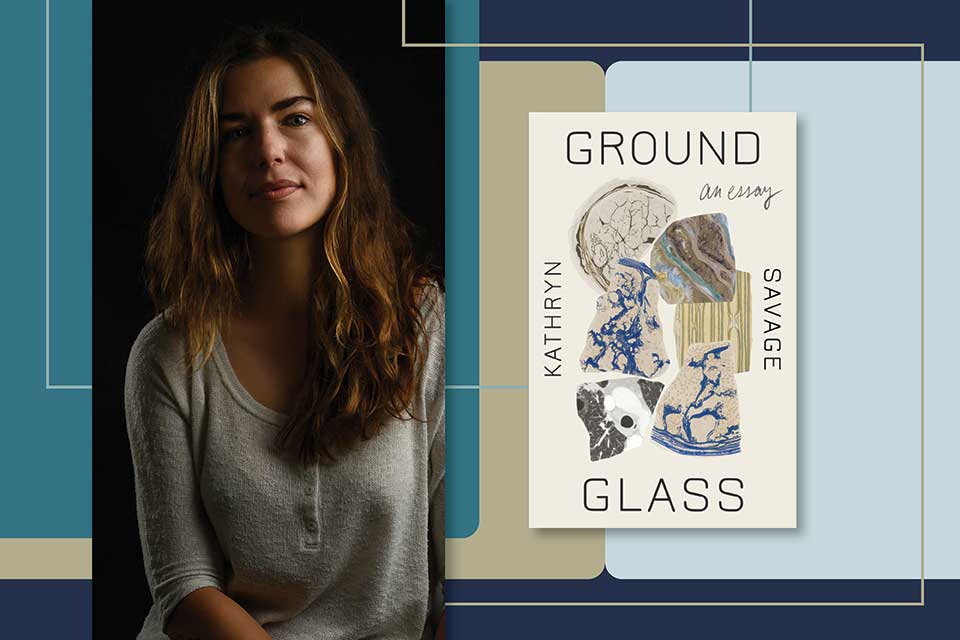

Kathryn Savage’s Groundglass (Coffee House Press, 2022) explores the health harms of living in a polluted world. The essay, closer to poetic elegy than journalism, begins after her father has died from a type of cancer that occurs at higher rates in polluted areas. Savage grew up in a fence-line neighborhood in the industrial Midwest, neighborhoods also called “sacrifice zones” because living adjacent to metal recyclers, power plants, and tar-shingle factories can harm one’s health. Her essay is attentive to language and keeps company with Maggie Nelson’s lyric investigation into the Superfund pollution at New York’s Gowanus Canal, one of America’s most polluted waterways, in Nelson’s genre-defying Something Bright, Then Holes. Groundglass is a reckoning with the stakes of living in a toxic world, both personal and environmental. I spoke with Savage about the ideas that inform her debut and the process of writing it.

Jennifer Croft: What is groundglass, and how did you come to the term as your title?

Kathryn Savage: Groundglass is an ill-defined small swell of cells, seen on CT scans and X-rays. The hazy spots were found on my father’s scans, by his oncologist. Groundglass opacities can indicate the presence of cancer cells—or not. Literally and figuratively, groundglass opacities are gray areas. When I was young, we lived in an industrial Midwestern neighborhood. I believe our geographic proximity to pollution harmed my father’s health, decades later, and caused me to develop asthma, but I lack proof. When illnesses may be caused by pollution, it can be so hard to prove causality.

The book is a mix of memoir and reportage and an exploration of the slow violence of industrial ecological and health harm, nationwide. I grew up next to a brownfield in Minnesota; the book investigates communities who live close to brownfields and Superfunds. When I started researching the medical and scientific aspects, I interviewed oncologists, scientists, and toxicologists, trying to grasp the relationship between pollution and health. What was refrained is that ambient exposure to toxins—and the impact of this overtime—persists in a gray area. Groundglass metaphorically held the challenges of knowing how, precisely, pollution had harmed my family.

Croft: I'd love to hear you talk a little about the language of cancer and what it has words for and what it passes over in silence.

Savage: My father was hard-working; he wanted to work at his cancer treatment and become well again. But the survival rate for him after diagnosis was less than 6 percent. His medical team encouraged his efforts to rest, eat well. I started to question—not his desire to work to live—but what is lost when cancer survival is so deeply enmeshed with individuality. The section of the book you are referring to is inspired by three works: Audre Lorde’s The Cancer Journals, Anne Boyer’s The Undying, and medical anthropologist S. Lochlann Jain’s Malignant: How Cancer Becomes Us. “Framing survivorship as a personal accomplishment,” Jain writes, “further separates cancer causation from its manifestations.” Jain asks, Where is cancer? “Is it in the body or the culture around it?” If cancer is imaginatively aligned with genetics and personal habits, then we miss, I fear, a greater exploration of the social and environmental factors that can lead to certain cancers.

Moreover, living next door to extractive industries that pollute neighborhoods and harm health is a structural inequity. Disproportionately, Superfund pollution harms the health of communities of color and low-income communities, nationally. What the language of cancer passes over in silence is culpability among big businesses responsible for environmental pollution to communities who are most affected. After my father died, I started to question: Would there be more social responsibility to individuals if a clearer understanding of the links between environmental pollution and disease were better understood? I suspect a shift in attitude and understanding would benefit more of us.

Would there be more social responsibility to individuals if a clearer understanding of the links between environmental pollution and disease were better understood?

Croft: You included some other perspectives in this memoir; I’m wondering if you could tell us about Keisha Brown and Rebecca Jim, for instance, whose points of view and ways of thinking contribute so much to the whole?

Savage: In 2020 an Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) report using census data revealed 200 million people—roughly 61 percent of the US population—live within three miles of Superfund sites or brownfields. Poet Forrest Gander opens his elegiac collection, Be With, with the line: “The political begins in intimacy.” Grief is intimate; so is home. Researching Groundglass, I met many people who lived near industry, and we all had stories to share about health harms likely caused by proximity to pollution. Including other perspectives, and especially those of phenomenal environmental justice activists like Keisha Brown and Rebecca Jim, was vital. I wanted to present readers with a chorus, not a solo.

I got to know Rebecca Jim, who is a Cherokee elder, environmental justice organizer, and Tar Creekkeeper, when I was living in Tulsa, Oklahoma, during the years after my father died. She is the founder of LEAD (Local Environmental Action Demanded), an organization whose mission is to achieve environmental justice in northeast Oklahoma. Jim has been working to clean up Tar Creek and the waterways surrounding a very large Superfund site, polluted by mining waste, for over forty years. It is easy to be discouraged in the face of ecological violence, but as Jim says, “[Tar Creek] can be repaired—it’s not nuclear waste. This is fixable.”

Keisha Brown is a resident of North Birmingham who works with the environmental group GASP (Greater Birmingham Alliance to Stop Pollution), advocating for the cleanup of industrial air contamination in her community. Both women are leaders, pushing for more protective legislation against area polluters. I interviewed Keisha Brown and Rebecca Jim, and their testimonies appear in the book. Their points of view and ways of thinking contribute so much to the whole—you are absolutely right. Also, ecologies are circulatory and interconnected. Formally, I hoped the book would show connections between various people and places, each navigating the harms of pollution.

Croft: Groundglass is rich with all kinds of interesting information about so many different subjects. How did you do the research for this book?

Savage: Because so much of the planet has been polluted by late capitalism, the ways our bodies are porous and interact with environmental toxins was a large topic. I set out to research two classifications for contaminated sites from the EPA, brownfields and Superfunds, terms for polluted areas I’d personally lived near, to orient myself geographically and give the book limitations and a frame. At first, I expected the research to be place-based and immersive, but I ended up doing a lot of it from home due to the Covid-19 pandemic. In-person interviews became phone interviews. My editor, the very wonderful Lizzie Davis, helped me develop scenes from a research process borne in isolation. I am very grateful to Davis, who is an amazing editor and translator.

Croft: I was intrigued by another of the terms you mention, solastalgia. Can you talk about that concept a little?

Savage: Solastalgia is derived from nostalgia and is a word to describe ecological grief. The feeling of solastalgia is homesickness for a familiar yet disappearing place, due to conditions beyond one’s control like climate change, mining, flooding. Unlike nostalgia, solastalgia is anticipatory grief—mourning tied to the future. I felt it the other day as fires were burning throughout Canada causing the sunlight over my child’s baseball field to bronze strangely like a penny from haze. I watched him run with joy while reading air-quality alerts on my phone, and I felt solastalgia. Climate catastrophe creates grief that’s forward-looking; the dread of “tomorrow will be worse.”

Croft: What are ecologies of entanglement? How do they function metaphorically for you, too?

Savage: Ecological entanglements are a reminder that environments and bodies are spongey. We absorb; we seep. The scholars who introduced me to ecological entanglements, conceptually, are Michelle N. Huang’s writing about the great Pacific garbage patch; Nicholas Shapiro’s writing on “sensuous reasoning” and attunement to domestic formaldehyde; and Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing’s book—which I recommend enthusiastically to all—The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Each writer describes the ways the material world moves across temporal, physical, and geographic distances.

Ecological entanglements are a way to describe complexity, complicity, and responsibility to all the living.

Around the time I was reading their work, I was also buying honey from a beekeeper in Oklahoma who keeps bees at a remediated Superfund site. The site is now a clover field. One day, discussing honey, he shared with me that when I eat any honey, I eat traces of what the bees ingested. I kept thinking about how honey holds traces—of clover, remediated soil, or carcinogenic weed-control spray blown onto nectar sources from a manicured yard. I was also learning about body burden, the load of environmental toxins we hold in our bodies. As I came to understand more about body burden and bioaccumulation, that toxins can be passed onto future generations, against one’s will, as when breast milk contains traces of dioxins a mother had ingested, I kept thinking about entanglements—ideas were tangling up. I started to see my body as a gathering site of both genes and the made world. Ecological entanglements are a way to describe complexity, complicity, and responsibility, I think, to all the living.

Croft: I was struck by your use of diverse images throughout the book—how did you choose what to include, and I’m especially curious about how you chose what not to include (i.e., how did you set visual limits)?

Savage: As a reader, I love when visual imagery is paired with essay and poetry. I am a huge fan of Victoria Chang’s Dear Memory: Letters on Writing, Silence, and Grief. I love the role photography plays in your staggeringly beautiful memoir, Homesick. One of the best books I’ve read in recent years is Kenyatta A. C. Hinkle’s SIR. Hinkle is an interdisciplinary artist and writer, and her work blends family photos with historical records, theory, and fragmented micromemoir. As a writer who endlessly admires works where visual imagery is central—and widens the lyric sensibility of the text—I wanted to include images.

Over time, Groundglass became more essayistic. I considered cutting the imagery altogether, but I wanted to retain some visual elements. I included aerial maps to specialize neighborhoods alongside industrial polluters. Pollution can be hidden in plain sight; showing adjacency, clearly, was important to me. But I learned I’m not a visual thinker. I struggled with layout and the collage aspects. If I were to move beyond language and into a space of greater cross-disciplinary focus again, I would ideally collaborate.

Ultimately, I’m very interested in how daily moments and ephemera can speak to large-scale events and histories. I love works that stitch personal and communal stories together. I think this is what lyric essay can do that journalism cannot: attend to the intimate, the occasional, the personally consequential. The groundglass, so to speak. All those hazy parts of life that are half-known and haunt us.

Editorial note: “The Long Night,” an excerpt from Groundglass, appeared in the July 2022 issue of WLT. Savage has also interviewed Dorthe Nors, Kathryn Nuernberger, and Naja Marie Aidt for WLT. In November 2022 she took part in the panel “Red Dirt and Brownfields: Humanities Perspectives on Ecological Restoration in Oklahoma” with Rebecca Jim, Laurel Smith, Todd Stewart, and Loren Waters.