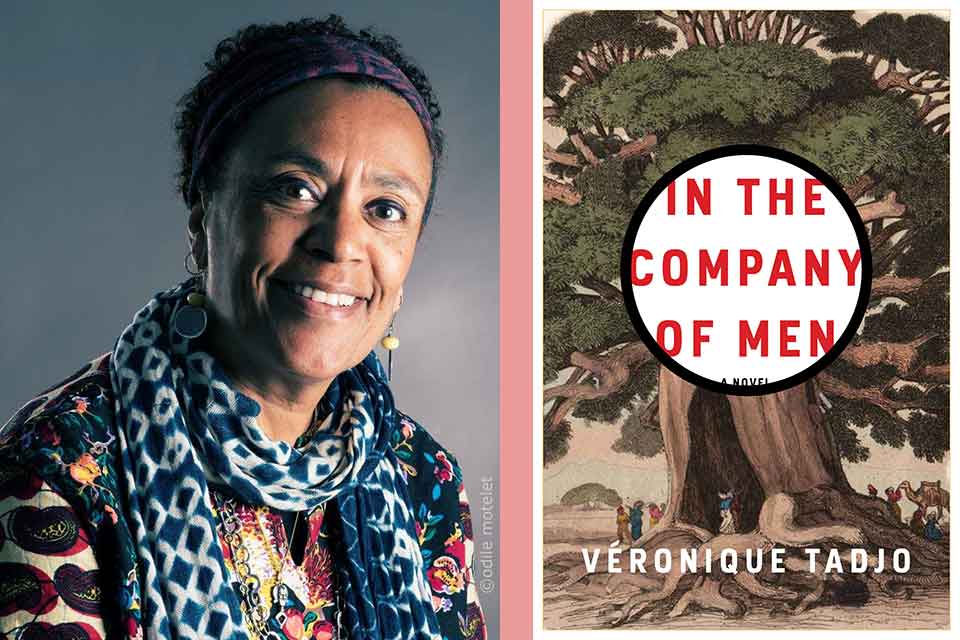

“Learning Again How to Live”: A Conversation with Ivorian Writer Véronique Tadjo

Beginning in March 2014 and lasting for roughly two years, the Ebola outbreak ravaged the West African countries of Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone, infecting more than 28,600 people and killing more than 11,300. Ivorian writer Véronique Tadjo’s new novel, In the Company of Men (Other Press, 2021), revisits the epidemic from a variety of angles—inhabiting the voices of doctors, nurses, patients, and researchers, as well as the virus itself, the very bats blamed for spreading the disease, and the wise and omniscient baobab tree. The roots of the calamity, the baobab warns, run much deeper than we think, symptomatic of the damaged relationship between man and nature in our modern world. And as today’s coronavirus pandemic has made painfully clear, the threat is only getting worse. “Will future outbreaks—and they will inevitably occur—strike the villages in the forest, or the big cities?” one of the book’s witnesses asks. “Are we aware that this isn’t the end, but only the beginning of a lengthy battle?”

Anderson Tepper: Hello, Véronique. How are you and how have you coped with this past year? Were you busy translating In the Company of Men into English?

Véronique Tadjo: I am well and have been working on several literary projects, including the translation. I hope that the difficulties we are experiencing will ease off gradually.

Tepper: I’ll begin with the obvious: Your book focuses on the West African Ebola epidemic but warns of the potential of a more global crisis. What were your thoughts as you were preparing your novel for English publication in the midst of the Covid pandemic?

Tadjo: The book first appeared in French in 2017. At the time, I had no idea about Covid-19. But during my research, I came to realize that the threat of another epidemic happening again was real. After all, in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Ebola was discovered in 1976, and the country had already experienced more than ten outbreaks. But because they were located in remote rural areas and caused a relatively small number of deaths, nobody paid much attention to them. It wasn’t expected that the virus would jump to West Africa, though.

Working on the English translation was strange in a way, but it confirmed my understanding that epidemics should not be given nationalities. Covid-19 may have started in China, but it is everybody’s problem now. We should accept that viruses know no boundaries and are not attached to anybody in particular. When working on the English translation, I was also struck by some of the similarities between what we are experiencing today and what happened during the Ebola crisis. We feel isolated and fearful for the future. The economy has slumped and we often contest political authority and the decisions governments take on our behalf. We also realize that science is not quite as straightforward as we initially believed.

Tepper: I’m curious: What does the title, “In the Company of Men,” refer to?

Tadjo: Humans have this belief that they own the earth and every other living creature in it. Their overexploitation of natural resources has created an imbalance that is threatening the planet’s stability. The title indicates the point of view of nonhumans observing the actions of the human species. It came to me during the process of imagining what the gaze of nonhumans would be if directed at us. They are our companions: What do they think of us? It is also a reminder that we are not above nature but part of it, and much more dependent on a fragile equilibrium than we think.

The title came to me during the process of imagining what the gaze of nonhumans would be if directed at us.

Tepper: I remember reading your earlier book, The Shadow of Imana: Travels in the Heart of Rwanda, and being struck by how you wove together on-the-ground research and testimonies with imaginative elements to explore the Rwanda genocide. Did you use a similar method with this book?

Tadjo: I have an aversion to telling a story in a linear form. I prefer not to, because I think that is not how it happens in our heads. I want to open up avenues and interact with the readers. I like to believe that presenting different points of views is the surer way of getting closer to the “truth.” We need to accept the complexity of life so we can make informed choices. I also think that we must never cease to learn. If we care about something, then we should continue trying to go further.

My wish is to look beyond traditional novelistic genres and their obedience to plot-driven action. I keep a thread, but plot and character are tied to the diversity of our life. I also came to this method because I was influenced by African oral tradition in which several genres like poetry, song, myth, and history are mixed. The bat in the book is in fact representative of what I am trying to do. I am fascinated by its duality—at the same time a mammal and a bird. It’s an animal that tells us a lot about adaptation and the need to recognize that nature changes all the time. It is this richness that we must preserve.

Bats tell us a lot about adaptation and the need to recognize that nature changes all the time. It is this richness that we must preserve.

Tepper: How did you decide on the different characters who would speak in the book? Were you looking for a more encompassing view of the crisis?

Tadjo: I could have added more characters. In the end, I settled for those who touched a particularly strong chord in me. At times the characters came as a surprise when, in the course of my research, I discovered the importance of their roles in the fight to end the epidemic. For example, I did not know that there were teams of volunteers going around villages to explain what Ebola was and what people should do to protect themselves. These community-led campaigns were a revelation for me. Another discovery was the existence of chlorine-sprayers and how essential their role was. It wasn’t glamorous to douse disinfectant, but it was essential to the survival of the medical teams. What nurses had to go through also baffled me. They faced constant danger in taking care of sick patients when they often did not have adequate protection. I wanted the narrative to be about kindness and solidarity as well, because without that nothing can succeed. I believe in readers being active participants. I want them to continue the stories where I leave off.

Tepper: At the center of the narrative is the baobab tree, “the first tree, the everlasting tree, the totem tree.” Tell me more about the importance and symbolism of the baobab.

Tadjo: The baobab tree is Africa’s iconic “tree of life.” It is an ancient tree, and some of its species date back to 200 million years ago. Baobab trees grow in thirty-two African countries. They can live for up to several thousand years and reach up to thirty meters high. They provide shelter, food, and water for animals and humans. The fruit of the baobab is one of the most nutrient-dense foods in the world. As a consequence, this majestic tree appears in many tales. It also has the added advantage of being easily recognizable and universal, as it grows in Madagascar and Australia as well. The baobab in the story represents Memory: the memory of the place of humankind in history.

The baobab in the story represents Memory: the memory of the place of humankind in history.

Tepper: The virus divides communities, families, even lovers. As the baobab observes, “This plague is worse than war. A mother, a father, a son can become a mortal enemy.” How did it attack rituals and traditions as well?

Tadjo: The Ebola virus changed the way communities lived and buried their dead. Touching, helping, caring became dangerous. Pity became a death sentence. More than in the West, African societies give precedence to the collective. “It takes a village to raise a child” is a well-known African proverb. It is the community that makes the child, helps it grow in a safe and healthy environment. The burial rites in traditional African religion—Animism—are complex. Like those of the Egyptians, where the dead must be accompanied to the other side of life. So, not being able to carry out these rites was a kind of curse. Some family members would rather hide the corpses of their loved ones than let them “go” without a proper burial. That’s why in the fight against the epidemic, medical experts finally understood that science alone was not going to be enough. They needed to talk to the people and convince them to make compromises. In the end, it was a question of negotiating what was acceptable and safe and what had to be banned.

Tepper: Ebola was a wake-up call to the world, but were its warnings in many ways neglected since it was contained to just one region? And how have these West African countries responded to coronavirus? I saw that there have also been new cases of Ebola reported in Guinea recently.

Tadjo: Important lessons have been learned from the Ebola epidemic in terms of prevention and preparedness. I am not saying that the situation is perfect now, but there are vaccines against Ebola today, and they have been dispatched to Guinea where the recent outbreak is occurring. The doses are mainly for medical workers. People are aware of the danger that Ebola poses and are much faster at reacting to an emergency. Nevertheless, it seems that many more lessons should have been learned, especially regarding medical infrastructures and primary care. Africa is still lagging behind, aside from a handful of countries.

Regarding the response to coronavirus: although it took a while, vaccination campaigns are starting at last. There was a lot of vaccine-hoarding from rich countries. Some governments acquired much more than they needed to protect their populations—often three to four times more. COVAX, an international mechanism, has been put in place to provide Covid-19 vaccines to low- and middle-income countries. There is some cautious hope that the situation will improve. But at the moment, we are talking about only 20 percent of the African population that will be immunized by the end of the year. It’s not enough, but it’s some progress. Apart from Southern Africa, the continent has been relatively spared the worst of the pandemic. But the situation is very fluid, and the different variants that are circulating at the moment are worrying. On the economic front, the impact of the global financial recession has deepened inequalities.

Tepper: One of your characters, a student volunteer, says, “It will take years for us to recover from what we’ve lived through. And also to forget.” I’m wondering about the lasting impact of Ebola, especially among the young—“Ebola children,” as you refer to them in the book.

Tadjo: The Ebola epidemic has caused huge trauma in Africa. After it was contained, a kind of silence ensued. It almost became a taboo subject for many people because of the suffering and stigma that it had generated. I thought that it was necessary to revisit the events so we could take stock of what had happened on many levels. The epidemic left a lot of scars. It seemed to me that literature could throw a different light on the events. Orphaned children, for example, are part of a generation that grew up with Ebola and its aftermath. We have a particular responsibility toward them.

Tepper: A village elder has one of the last words when the Ebola crisis is finally contained: “After dying several times, we must learn again how to live.” What are some of the things we will especially need to relearn and rethink about our ways of life?

Tadjo: It has been said before, but it is worth repeating: We must rethink the relationship that exists between humans and nonhumans—and maybe arrive at a pact of nonaggression. We have to continue to find solutions to the problems that we have created ourselves. The pandemic has shown us the limits of the relentless progress in which the world was engulfed, like a blindfolded, speeding driver. We know today that the impossible is possible, that what we took for granted can be taken away from one day to the next. We have to reshape our own destiny and not expect a happy ending and a straight return to “normality.” Was anything ever “normal” in the way we lived? We should endeavor to embrace more possibilities. And it seems to me that we will be able to do this if we learn to share and collaborate in a much wider sense.

February 2021