The Mystery of Who We Will Become: A Conversation with Holly Wilson

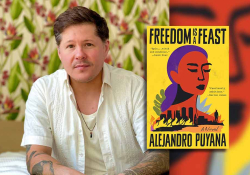

Right: Holly Wilson, Girl in the Red Dress (2019), 60 x 29.75 x 1.625 in., oils and cold wax on birch panel / Courtesy of the artist / hollywilson.com

Holly Wilson is a multimedia artist whose artwork appears on the cover of the May–June 2022 issue of World Literature Today. Whether working with bronzes, paint, encaustic, photography, glass, or clay, she captures stories of both the sacred and the precious. A native Oklahoman and a member of the Delaware Nation and Cherokee Nation, Wilson’s work has been exhibited internationally in corporate, public, and museum collections as well as in private collections around the world.

Alexandra McManus: Your piece Girl in the Red Dress (2019) is featured on the cover of the May–June 2022 issue of World Literature Today. Thank you for your contribution, and congratulations! How did you decide to become an artist?

Holly Wilson: I am not sure one decides to become an artist. I feel we all have art in one form or another in each of us. It was the ability to tell a story without words that probably drew me in. I struggled most of my educational life with reading and writing, not knowing till senior year of college that I was dyslexic. I was told that when I was young, I would wake my dad up at 5:00 a.m. with his pencils, eraser, coffee cup, and that we both would sit and draw. He was working on an architecture degree, and I was working on my own art. I feel that has never really ended. It is a place that I can get both lost and found within.

Holly Wilson: I am not sure one decides to become an artist. I feel we all have art in one form or another in each of us. It was the ability to tell a story without words that probably drew me in. I struggled most of my educational life with reading and writing, not knowing till senior year of college that I was dyslexic. I was told that when I was young, I would wake my dad up at 5:00 a.m. with his pencils, eraser, coffee cup, and that we both would sit and draw. He was working on an architecture degree, and I was working on my own art. I feel that has never really ended. It is a place that I can get both lost and found within.

McManus: Where are you from, and how does that affect your work?

Wilson: While visiting New York I was asked once if I felt like I was home, Lenapehoking. I am Delaware Nation and Cherokee Nation born in Lawton, Oklahoma, and the idea of home has been a thought for me on all my travels. I ask myself, “Could this be a place I would call home?” I feel a connection to certain places as if I have been there—like a déjà vu, a memory in a thick fog—but when I think of home, it is not a place but the people I am with. It is that feeling you get when you know you can relax and just be. For me, that is my family with our two oversized dogs, three cats, and the neighbors’ chickens who visit me daily; sometimes they leave me eggs as gifts.

I live in Oklahoma, where the sky is so big it feels like you can see both sides of the world. The sunrises are filled with pinks and purples that stop you in your tracks, and the sunsets fill the sky like a red fire that does not burn but can make me tear up from its beauty. The weather can be extreme, and sometimes come all at once, but the one constant is the wind; she carries the smell of the rain, the sounds of the cicada in the late summer, and the seeds of tomorrow with her, and when the air is still you ask where she is. I can sit in the field and close my eyes and know I am home. I feel the wind on my face and hear my family in the distance. I carry my heritage with me wherever I go. It is my heartbeat low and deep in my body; it keeps me centered and reminds me I never walk alone.

I carry my heritage with me wherever I go. It is my heartbeat low and deep in my body; it keeps me centered and reminds me I never walk alone.

McManus: When admiring your work, I’m fascinated with the depth you seem to create with each piece, especially the ones that cast shadows. What exactly is your art process like?

Wilson: I start with a story in my head and what I want to say or show, then build from there. This could be in bronze, paint, encaustic, clay, glass, photography, wood, and any combination that translates the story.

Shadows I do work to create in the sculptures because they represent the idea of memory; shadows move with the light, the day, and so too does our memory of a time or a place.

McManus: Many of your pieces feature masks, which you’ve said before function as multilayered elements in your art. In this issue of WLT concerned with muses, what sort of themes does the mask featured in Girl in the Red Dress represent?

Wilson: In a strategic trickster twist, I feature children, often masked, as a tool to bring the viewer into my story that on the surface seems benign or sweet but upon closer reflection addresses much deeper and challenging issues. Masks are multilayered elements in my work. Simultaneously, they reference traditional Delaware and Cherokee stories that my mother told me as a child and symbolize transformation and obfuscation. Masks are a mechanism to hide or obscure our true intentions, acting as a wall between us and the world, at times protecting us or others. They are also agents of transformation that allow one to become more than what they were, to become powerful or sometimes dangerous. The strategy is to subvert narrative expectations.

Girl in the Red Dress has many of these elements. It is that mystery of who one will become. The eyes are of my daughter when she was much younger. It is the eyes that hold so much information. They can look at you with a kind of knowing, and it is without words that I can hear her voice.

McManus: Is there a specific environment or material that’s integral to your work?

Wilson: I use bronze for the strength that it gives me in the work—I have the ability for a figure to be up on its tippy-toes. In the use of some materials, I try to use them for their meaning in the work. So, the use of sterling silver represents that which is precious because it is a precious material.

McManus: A curator at the Springfield Art Museum noticed how many children feel a connection to your artwork. Why do you think that is?

Wilson: I think children are unguarded and open—they see many things for what they are. I use this same quality I see in them, with the use of a child as the figure to show the unguarded moments of life.

McManus: Over time have you noticed your teaching career, or even your students themselves, affect your art process, style, or inspiration?

Wilson: I only taught for three years in public school in the late ’90s. It was your standard drawing, two-dimensional, very early process classes for a Houston public middle school, and at the high school level I taught digital art in Katy, Texas, which I was not doing in my own work at that time. I now teach a few summer classes, but it is more about the technique to the process of bronze casting and/or 3D encaustic. I work with them on their art to use my process to create their vision. I do not teach classes where you are going to make an object that I’m making. I am very much interested in the processes. I have come into your hands and take your work to another level. I really feel that the knowledge is a gift. I hope the students will take and make their own to work for them.

We all have lived lives full of joy, loss, sadness, and hope. We are all people, and it is the connection to each other and hope that I believe in.

McManus: Is there anything you think people would be surprised to know about your art or you yourself as an artist?

Wilson: A few things people are surprised to find is that I cast my own bronze work, and each is a unique cast, so there are no editions or copies. To me each work is a story, a life, and it is unique.

When I cast flowers or organic materials, much of the time they are from real flowers or sticks.

McManus: What do you hope people take away from your art? What do you want to accomplish?

Wilson: Hope and connection. We all have lived lives full of joy, loss, sadness, and hope, we are all people, and it is the connection to each other and hope that I believe in.

April 2022