“Silence Became My Mother Tongue”: A Conversation with Sulaiman Addonia

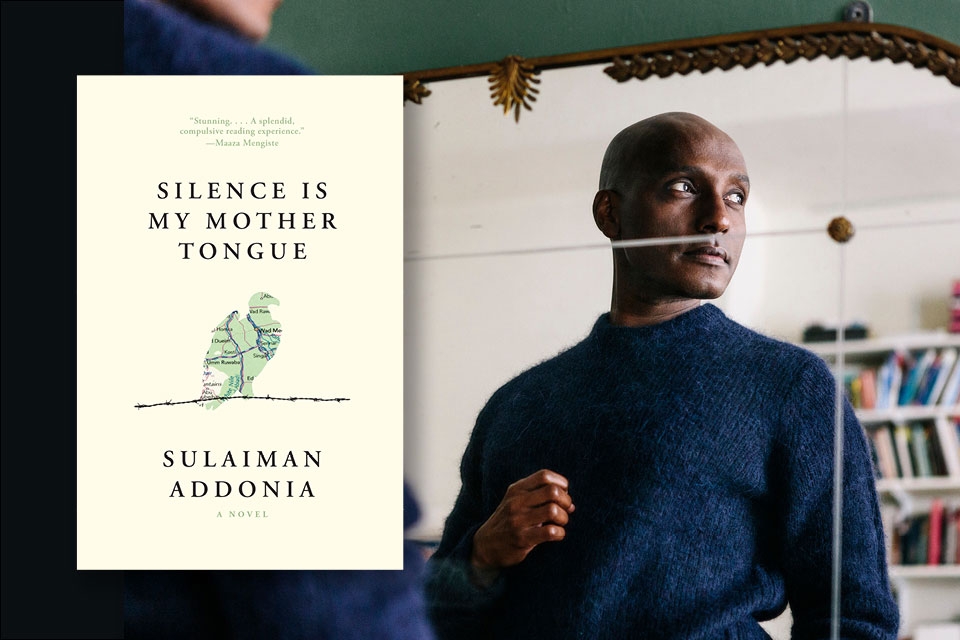

For me, one of the most astounding books of this past year—which may have slipped your attention due to the pandemic—was Silence Is My Mother Tongue, the second novel by Ethiopian Eritrean writer Sulaiman Addonia (@sulaimanaddonia). Published last September by Graywolf Press, the novel is just now beginning to get the recognition it deserves: it was recently shortlisted for the Firecracker Award for Independently Published Literature and is a 2021 LAMBDA Literary Award finalist. Set in a refugee camp in Sudan, the novel defies expectations—shimmering with sensual detail, it charts the daily encounters and erotic dreams of an extraordinary cast of characters, with the inseparable siblings Saba and her mute brother, Hagos, at its center.

Of course, since war erupted in Ethiopia’s Tigray region this past winter, Addonia’s work has only taken on more resonance. “I have been looking at the pictures of refugees fleeing Tigray and waiting outside the United Nations refugee agency office at Hamdayet in Sudan,” Addonia wrote in a New York Times editorial in late November, “the place through which my family and I passed decades ago, on our way to a refugee camp further inland. I was struck by the eyes of young children. Their gazes retreat and shift, as if their wide eyes have already become the trenches into which they will hide their childhood.”

We spoke by email—Addonia lives in Brussels—about his own childhood, the language of silence, “reading” life, and much more.

Anderson Tepper: Hello, Sulaiman. First of all, I’m curious about the book’s title. Where is this phrase from, or did you invent it?

Sulaiman Addonia: I want to say I “invented” the title, but I am not sure “invent” is the right word. I was patient with the title. I worked for a long time without one. And this title came to me late one night, about eight years after I started writing the novel, while I was walking around the ponds of Ixelles, in Brussels. The way it came showed me that I had carried it within me for a long time. It was ready, formed, and made utter sense to me. I was a silent and silenced child in the refugee camp. When my mother departed for Saudi Arabia (I was around three at the time) and left me behind with my grandmother, I fell silent. It was as if my mother took her language with her. Circumstances might lead you to the world of silence, but once you are there—and discover its beauty and the richness of its vocabulary—you embrace it. Silence became my mother tongue. Silence itself seems to be a character in the book, in the way it lives in the main characters and swims alongside the language and the words on the pages.

Tepper: The novel shifts to the first-person perspective a couple of times, but for the most part it floats freely around the camp. We see characters bathing, dreaming, making love, recalling their previous lives. Was this a way to achieve more intimate access to their inner lives and desires?

Addonia: Perhaps. But it could also be because that seemed the only way to write these characters. I think if I step back from this book and observe it as a reader, I can notice the influence of cinema. It was as if when I was writing it, I had a camera attached to my forehead that allowed me to zoom in and out, move left and right. I gave all the power of my imagination to this camera. I lost myself. Or, I should say, I transcended myself. When I am at my writing desk, I am not really conscious. And at that point, when I submit myself to the story, the characters write themselves. To be unconscious at your writing desk is to surrender yourself to the mysterious power of creativity.

Tepper: Saba is a remarkable character, fiercely independent and sexually polymorphous. “Nothing in this compound is what it seems,” she says. “We do our love differently here.” Why was it important to create a character who defies conventional gender roles and sexual taboos?

Addonia: These characters exist in real life, even if many of them are forced to live in the gray areas, the periphery of our societies. I think they are rarely explored because writers are conditioned by the norms of the society. All those rules of literature that advise subtlety and restraint are just another way of controlling writers’ imaginations. I realized all that at the beginning of writing Silence. I just couldn’t write some characters, like Saba and Jamal, who have their own ideas of sexuality and what desire means to them. When I noticed how conditioned I was by the societies I have lived in (Africa, the Middle East, and Europe), I put my pen aside and decided to work on freeing my mind. I isolated myself with books by Tayeb Salih, Anne Desclos, George Bataille, and Pasolini; with films, erotic photographers, feminist thinkers, poets and artists who challenged me. Liberated from judgment, I came out of that experiment with the freedom to follow my characters wherever they took me and to write them as they were. That’s why I say, “I wrote Silence, but Silence rewrote me.”

Tepper: You recently published an essay about growing up without books and how you learned instead to “read” life around you. What were some of the formative books you encountered when you finally started reading widely as a teenager in Saudi Arabia, despite censorship?

Addonia: The first one that shocked me and enthralled me as a teen in Jeddah was The Season of Migration to the North, by Tayeb Salih. Then there was Charles Dickens’s Oliver Twist. There were also books by Virginia Woolf, Victor Hugo—books I frankly couldn’t understand. But it wasn’t about understanding. It was about discovering a world beyond the black and white that the Saudi system tried to instill in us. The real world, with all its complexity and nuance, was only available in that smuggled literature.

I wanted to paint an Eritrean Ethiopian woman in the way Degas painted that French woman.

Tepper: Silence Is My Mother Tongue is dedicated to your former playmates as a kid, and elsewhere you’ve written: “It was this symphony with complex human notes, composed by ordinary people, that endeared me to our refugee camp.” When did you decide to write about this world and turn it into literature?

Addonia: After my first novel, The Consequences of Love, was published in 2008, I decided to treat myself and so I went for a short holiday to Paris. There, I went to a museum. I bought a book on the French painter Degas. Outside the museum, I sat in a café, and as I flicked through the book I saw Degas’s series of a woman taking a bath in a bucket, which was how we washed when we lived in the camp. Immediately, an idea came to my mind: I wanted to paint an Eritrean Ethiopian woman in the way Degas painted that French woman—so vivid, so complex, so alive—a work of art that negotiates history, the tragedies of life, with intensity and intimacy. I visualized my character in a bucket, in a hut, in a camp, somewhere in East Africa. The power of nudity appealed to me immensely. It was the gateway to intimacy and freedom because it allowed my characters to transcend their surroundings and live freely on my pages. It would take me ten years, but ultimately I think I painted my women characters in my own words.

Tepper: Now that you are an established author yourself, who are some of your contemporaries that you feel especially connected to?

Addonia: I’d say that at the moment I love books that have a bit of madness in them, a bit of playfulness, inventiveness, boldness. Books that have no message, no intention, just the pure magic of an artistic imagination and its crazy ways. So to that end, I’d say the book I feel particularly connected to is A Girl Is a Half-formed Thing, by Eimear McBride. Having said that, I want to mention some poets I’m reading at the moment, too, such as Jay Bernard, Rachel Long, Ocean Vuong, Warsan Shire. But I also want to stress that I don’t just read books. I also read paintings, photographs, rivers, music, lovers’ eyes, nature, trees. The sources of my inspiration are endless and not confined to one medium or entity.

At the moment I love books that have a bit of madness in them, a bit of playfulness, inventiveness, boldness.

Tepper: You’ve said that you spent the early part of the pandemic unable to write, but then were suddenly motivated to begin your next novel, The Seers, on your phone one day. What prompted this creative outburst?

Addonia: Well, I wrote all my books and essays in cafés, so when the first lockdown took place here in Brussels in March 2020, I was so worried. I couldn’t see myself functioning without writing and I couldn’t see myself writing from home. Then one afternoon, I was standing in front of the ponds of Ixelles when a name popped into my mind: Hannah. That was all. But it was as if she came attached to a rocket that landed inside my imagination. Such was her energy. I couldn’t look away. I wrote about her and her world on my iPhone.

Tepper: Tell me about some of your other literary projects in Brussels: the writing center you founded and the Asmara-Addis Literary Festival.

Addonia: In 2018 I founded a Creative Writing Academy for Refugees and Asylum Seekers and the Asmara-Addis Literary Festival (In Exile); and in 2020 I also co-founded, along with Specimen Press, a literary prize, To Speak Europe in Different Languages. There’s a lot to say about each of these: I founded the creative writing academy, for example, because I know how difficult it is coming to a new country, learning a new language, adapting to a new culture. I wish I had had the opportunity to go to a place where I could express myself when I first came to the UK. Also, I don’t like the term “the voice for the voiceless.” Everyone has their own voice, including refugees. What they need is a place to express it and tell their stories the way they want.

With the festival—named after the two capitals of my parents’ countries—I wanted artists from the diaspora to have the chance to talk about literature, art, and performance that mattered to us all. Most of the time when I get invited to festivals, I tend to be asked about the war, exile. I get it: it’s all part of my story. But so is art. I chose to become an artist. I spent ten years in Brussels writing one book. And to do it, I spent years researching art and photography, breathing paintings, listening to music, immersing myself in nature. So I, and many artists in the diaspora, have earned the right to talk about art, music, and the power of imagination, among other things.

Tepper: You’ve begun writing a regular column for a Belgian newspaper. What sort of subjects do you plan to cover?

Addonia: I’m so excited by this column. It will be about ideas, languages, art, nature, being a flâneur in Brussels, and learning Dutch. Basically, the things I love, and the things that inspire me the most.

I love art most when it operates on the edge.

Tepper: You’ve also started an Instagram page to further explore the “erotic” in your work. What will that involve? (I might need to join Instagram now!)

Addonia: Ha ha. Well, I’m still new to Instagram, so wait until I learn how to use it properly. Honestly, though, I love art most when it operates on the edge. The way nudity, sensuality, playfulness, and literary erotica can combine to give one’s imagination an edge is so poetic to me. So in a small way, I wanted to share some of those artists who inspire and provoke me, such as Namio Harukawa, Degas, Francesca Woodman, Leonor Fini, and many more.

May 2021