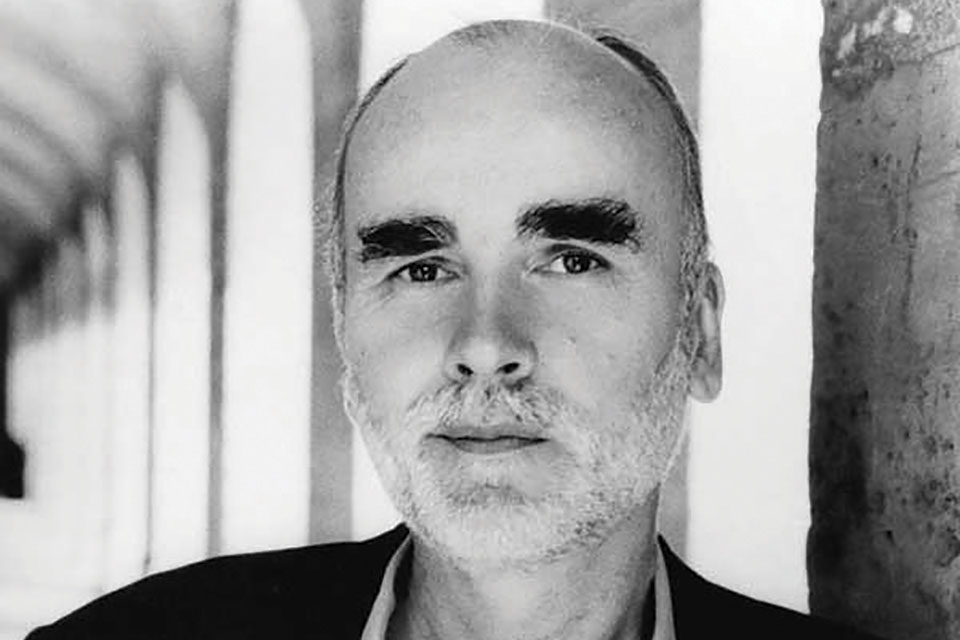

A Farewell to Adam Zagajewski

I was waiting for a tennis court on the lakeshore in Chicago when I read that Adam Zagajewski died. I have always considered tennis like writing: you practice to get into a rhythm, you wait for moments of inspiration, and sometimes you play out your imagination without feeling yourself thinking or moving at all. Zagajewski lived not far from there when he taught at the University of Chicago, and his poetry and essays always described how we live between banal moments of everyday life and sudden rousing flights of inspiration and clarity. I hope he would enjoy my comparison to tennis, as both can pull one into the sublime, though it is too late to ask him now.

Zagajewski’s work endlessly explored what it means to live and create, or to live through creating.

Zagajewski died on Sunday, March 21, World Poetry Day. He would appreciate the coincidence, as he has admired in his work how personal fates meet historical events. On World Poetry Day we lost our greatest poet—our great writer on writing, great poet on poets, whose work endlessly explored what it means to live and create, or to live through creating. He wrote beautifully about Rilke, who removed to a tower, waiting for his inspiration to overcome him like a tidal wave; about Osip Mandelstam, who died for his verses; and Gottfried Benn and Vladimír Holan.

His poetry follows a clear arc: first, the New Wave, the poet of political engagement and philosophy; then, the greatly lyrical and metaphysical poet, the poet of “To Go to Lvov” and “Try to Praise the Mutilated World”; and, finally, the poet of shorter, more private verses, of Asymmetry and Real Life. He is a master of the line break and of the poem-by-breath (in his essays, master of the complete paragraph). Zagajewski, the author of Mysticism for Beginners and Poetry for Beginners, continued the lineage of earnest poetry in Poland, holding out for redemption and not damaged by total irony, that he inherited from Czesław Miłosz, Zbigniew Herbert, and Wisława Szymborska. In many ways his death ends one of the greatest eras of poetry, not just in Poland but in the history of the world.

In many ways Zagajewski’s death ends one of the greatest eras of poetry, not just in Poland but in the history of the world.

Zagajewski is a poet of moments. He finds the eternal in brief revelation through the smallest details, in the face of an old teacher in a raindrop rolling down the window or in the dew gleaming on a suitcase at dawn. In “To Go to Lvov,” an ode to the lost place of his youth, which his parents fled for Poland, he describes the city of the past as something physical, something that spills out from glasses but can also be trimmed with scissors:

. . . there was too much

of Lvov, it brimmed the container,

it burst glasses, overflowed

each pond, lake, smoked through every

chimney, turned into fire, storm,

laughed with lightning, grew meek,

returned home, read the New Testament,

slept on a sofa beside the Carpathian rug,

there was too much of Lvov, and now

there isn’t any, it grew relentlessly

and the scissors cut it, chilly gardeners,

as always in May, without mercy,

without love, ah, wait till warm June

comes with soft ferns, boundless . . .

(trans. Renata Gorczynski)

He concludes that he can go there, “after all / it exists, quiet and pure as / a peach. It is everywhere.”

Lvov is everywhere, and Zagajewski attends to the ethereal and unseen, the zone of Lvov, in his other poems. In “Self-Portrait,” he calls himself “a child of air, mint and cello,” and writes that “sometimes in museums the paintings speak to me / and irony suddenly vanishes.” In Another Beauty, he notes that “in childhood, sometimes trees murmured even on windless days.” (Another Beauty and Slight Exaggeration are underacknowledged masterpieces: Zagajewski practices a form of short anecdotes, essays, philosophical reflections, passing observations, and diary entries that allow the reader to linger in moments and questions—as in his poetry, as in his life.) Later in that book he asks, “Why are detective novels so boring? Because they deal with a single mystery, the simple question of who killed Mr. L. But there’s one real mystery, one real question: What is the world? What is fire? What is air?”

I weep for the poet because I weep for these earnest moments of being and thought. In 2002 he published A Defense of Ardor, in which he speaks up for high style and the sublime. In his acceptance speech for the Princess of Asturias Award for Literature, he says, “Poetry is not in fashion; crime fiction, biographies of tyrants, American films and British television series are in vogue. Politics is fashionable. Fashion is fashionable. . . . Bicycles and scooters are fashionable, marathons and half marathons, Nordic walking; it is not fashionable to stop in the middle of a spring meadow for reflection. Lack of movement is harmful to health, doctors tell us. A moment of reflection is dangerous for health, you have to run, you have to escape from yourself.” Zagajewski writes from the spring meadow, that place of waiting and not-knowing, and his poetry shows us what we lose in the mindless pace of fashionable hobbies, commerce, social media, or so-called life. In “Elegy for the Living,” he laments: “The living exist, so light-mindedly, so nonchalantly, / that the dead are abashed . . . Above us, robinias blossomed, / and in the robinias, nightingales sang.”

Zagajewski writes from the spring meadow, that place of waiting and not-knowing.

Reading Zagajewski opened me to a literary heritage I had not known, and I communed with his work for many nights and days in my formative years. I saw him once when I was nineteen: my flight to Dublin had been delayed overnight, and I did not sleep on the plane, and I wandered on a large bus west to Galway, a city I did not know. Looking through the window I spotted his elbow-patched coat and his patient gaze cast out on the Liffey. The sight put me in a thrill: that was Zagajewski, my most beloved author, sauntering by the river. I needed to get off the bus, run out to him, tell him I loved his work. But my heart beat fast, the bus sped forward, and I did not tell the driver to stop.

The second time I saw Zagajewski I journeyed to Poland for the first time as a man. The country spoke to me: it spoke through the cobblestones and the birdsong in the trees at Planty Park and the voices of century-old men hobbling in woolen suits through the throngs of young people in the city squares. I attended the Miłosz Festival in Kraków, and at the last moment, as I waited for the speakers to discuss Miłosz and Herbert’s relationship, the quiet, esteemed man came in—I knew him from the YouTube videos and the inside flaps of books—and he sat in the chair right in front of me, holding his wisdom to himself, listening patiently and applauding with vigor at the end of the event. I stood next to him as we waited for the crowd to file out of the room, but I did not say a word.

Why? Was it because I was afraid? Was it because his verses spoke so clearly to me? Because his writing occupied my inner life so immeasurably and for so long that I could not say anything because no interaction could surpass that private experience?

As always, the paradox plays itself out: slowly the aura of the person vanishes while the work continues to materialize.

I was writing a book on Shakespeare at the time, and seeing Zagajewski made me realize that artists live in many ways, through their work and public appearances and community appearances and private lives. We could never recover many of those parts of Shakespeare, I knew, because they died with him and those who knew him. Now we have lost Adam Zagajewski. As always, the paradox plays itself out: slowly the aura of the person vanishes while the work continues to materialize. Every time we turn the pages it reconstitutes itself, and speaks, endures, and revives little moments of life and revelation.

I recently read Maria Stepanova’s In Memory of Memory, in which she advocates for the rights of the dead. They did not choose to have their stories told by us, she argues, or to have their things resold or their images dishonored on T-shirts and souvenirs. I have been trying to remind myself to speak of the dead in the present tense, because they have never left, they always linger in our personal memories, in our anecdotes, our lesson plans, our books that rustle and breathe. And we would not know what we know—we, the supposedly eternal, the always-better-than-the-past—without them.

Zagajewski was—is—the writer’s writer. He is the poet of tributes. His work describes what it means to write, and struggle to write, and it always returns to the writers who have died but continue to live through their work. He engages in an unending dialogue with the dead. He goes to them for wisdom, solace, and inspiration. Let us honor him by trying to uphold that faith in writing and the past. As Zagajewski writes in “Without End”: “Also in death we are going to live, / only in a different way, delicately, softly, / dissolved in music.”

In Polish when someone dies, you say the person odszedł, meaning they left or have gone. Come back to us, Adam, come back. Come back to us. But you do not need to read this or hear my pleas. No, because I know you will come back. You will come back to us. I am certain. You will come back. If only we open your pages, and wait for you, and listen.

Chicago