99%

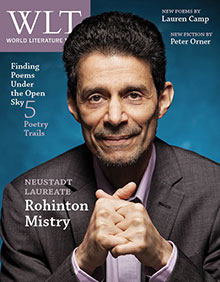

In the first translation of his work into English, South Korean writer Kim Kyŏnguk imagines an ad executive confronting a man who may be his former school nemesis. And as in other anxious moments, he craves one thing: 99 percent chocolate.

There are times when I want something sweet. Like when I’m up all night waiting for an idea that never comes, or I’m waiting anxiously for my ad concept to be accepted, or I get so curious I can’t stand it. Times when the dwarf in my head grumbles, Come on, give me something sweet! That’s when chocolate comes to the rescue. The sweetness melts in my mouth and warms my heart until it ferociously pumps blood to every tissue of my brain, and then the dwarf in my brain calms down like it never asked for it in the first place. The chocolates I like are the ones with the crunchy almonds. I love the crunchy texture, plus the nuts help stimulate brain activity. That’s why my desk drawer and my pocket are never without an almond-studded chocolate bar. The first time I saw Steve Kim, the dwarf in my head just bawled for sweets. Never before had I craved it when I met someone. Weird, isn’t it?

He was a sensation from the beginning. His first appearance was on a Monday morning when the yellow dust of spring was running riot. The CEO took him around in person and introduced him. We’d been hearing since the end of last year that he was being scouted, and I was almost expecting to be introduced to him. When we fell way short on project acquisition the first half of last year, we heard a lot about staff reorganization, system revamp, and such. To be honest, adversity was nothing new in our company. In the advertising industry, too, the rich were getting richer and the poor were getting poorer. The big projects were always gobbled up by a handful of big companies that had a gigantic network of human resources and generous funding. The small firms tightened their belts and concentrated on the niche market, where they’re more competitive because they can afford to be offbeat. That left the middle-sized outfits like ours: we were the ones with the most problems. Some predicted we’d end up merging with a company like our own, but the majority expected to see deep cuts in our workforce instead. Since we were living in an age when even people with a career are practically unemployable once they’re fired, everyone, including me, sat at his desk like he was part of the furniture. Even the production director, who would rather bake in a sauna than have lunch, had been showing up regularly at the company cafeteria. As for me, I laid as low as I could. I even stopped texting with Misŏn. I’d met her in the company’s bicycle club, and we’d started dating. She works in general administration. Nobody knows about our relationship.

“He’s going to be the next Midas of the ad industry,” the CEO said. “He’s already a global expert, and he’s from America, the heart of capitalism . . .”

Unbelievable! I wasn’t used to hearing such praise from the CEO, who’s so skimpy with compliments for the staff, and my face prickled with embarrassment. But there he was next to the CEO, tall, confident, dignified—not a trace of nervousness on his face. His well-defined yet delicate facial features gave him a chic, urban look. The CEO was all hyper, like a countryside principal introducing a new student he’s worked hard to recruit from the city. I thought of the high school principal in G City, who had taken me around to the classrooms and introduced me to his students.

I’d been attending a high school in B City, but when my taxi-driver father had an accident and could no longer drive, I transferred to the school in G City, on a nearby island. It offered to waive my tuition, provide board, and give me a scholarship—the only way I could continue my education. The clincher was an outrageous incentive: the school would pay full tuition for any student who got into Seoul National University. On that small island with nothing to look at, a shipbuilding company pulled into port, and people and money followed it in. You could see blue-eyed foreigners who were almost certain to be shipbuilding engineers. They were mostly from Britain, Greece, or Sweden, all top shipbuilding countries.

My new school had lots of money and aggressively scouted ace students from the surrounding areas. The principal didn’t make any bones about his expectations for me. I was the top student at a prestigious school in B, a city known for its distinctive history and tradition. Not only was it unusual for the principal to introduce a transfer student in person, his extravagance made me want to go somewhere and hide: “I’m delighted to introduce to you a talented young man who will be the jewel of our school. Standing before you is Mr. Ch’oe, a gifted student who ranked number one at the prestigious high school in B . . .”

“I’m Steve Kim. Nice to meet you.” These words and a handshake he offered to every staff member. When it came my turn, at the moment I shook hands with him, I was swept with a sense of déjà vu.

“Have we met?” I asked.

He blinked quickly. “I can’t say. But people often ask me that—I guess because I look so common.”

He answered with a smile, revealing a glimpse of his straight white teeth. It was a flawless smile that could only have been acquired through thousands of practice smiles in front of the mirror.

* * *

Misŏn messaged me.

Kissing up to him already? I didn’t think you were the type.

What are you talking about?

You acted like you knew Steve Kim.

Who said that?

Everyone in the company knows now.

Bullshit.

You asked if you’d met before.

What’s that got to do with kissing up?

Whatever—but do you really know him?

How do I know!

Face it, if you acted like you knew him, then you kissed up to him—unbelievable he’s already a director at his age! Come to think of it, you’re both the same age.

I gotta go.

How about spaghetti for lunch?

I closed Messenger, took a chocolate bar from my desk drawer, shoved the whole thing in my mouth, and started munching. Already he was a hot topic in the company. Even this nonsense about me kissing up to him must have originated from the interest in him, not me. Whether people were eating lunch or drinking coffee from the vending machine, he was the subject of conversation. Conversation about him popped up everywhere he passed by.

“He is absolutely gorgeous. He has perfect ‘American manners.’” The women usually commented on his clean-cut looks and his nice comportment.

Men blurted comments about his position. “Even if he’s got it all, isn’t the company going overboard hiring him as a production director?”

“That position was ‘created’ for Steve Kim. It’s like making a rookie fresh out of high school into a relief pitcher.”

“What’s the general manager going to do—he’s ten years older.”

But when Sauna Pak, the general manager, arrived, everyone got quiet.

“Who’s got a smoke?” he asked, rubbing his hands together in anticipation.

Nobody answered.

“Oops! Nobody here smokes.—ha-ha—wait a minute—Ch’oe, you smoke.”

“I quit early this year,” I replied.

“Well aren’t you a determined son-of-a . . . You know what they say—don’t let your daughter marry a guy who quit smoking—ha-ha—all right, then, have a long and healthy life, ladies and gentlemen!” And with another empty chuckle, Sauna Pak turned away.

“He could get a rise out of the Buddha’s middle leg,” someone muttered.

Then, everyone looked at me to figure out what I was thinking. Sauna Pak was one of the founders of the company and liked to boast of his personal relationship with the CEO when they were “off duty.” He and I were from the same town. And when I started working here, he was my immediate supervisor, and he made no secret of his affection for me. I swear this had nothing to do with me being the first to make assistant manager. But my colleagues took a different notion on the situation, and when they had a drink or two they’d start talking.

“You have Sauna Pak on your side.”

That got my dander up. “Lay off Sauna Pak—he would never manipulate company politics to his advantage. And he never gets into fights even when it’s time to fight. You know his nickname sounds like the Korean word that means ‘Are we really fighting?’ Right? That’s how much he hates to fight. You got that?’”

The silhouette of Sauna Pak walking toward the far end of the darkened corridor resembled a crumpled cigarette pack with nothing in it.

* * *

Guess who showed up at the production meeting that afternoon. Everyone looked surprised. Hmm, a director at a small meeting like this? That was odd. And on his first day of work?

“I wanted to get into the flow ASAP. Don’t mind me. Business as usual,” he said, glancing about the gathering and never losing that soft smile of his.

The purpose of the meeting was to establish an ad concept for cup noodles. It was our second season with this one, but we were in trouble: a secret source had told us that slow sales had gotten the client thinking about switching ad agencies the following season. In recent years, acquiring a new project felt like trying to catch a star. So, we had to do all we could not to lose the projects we already had. A tension I had never felt before was roaming in the conference room.

People poured out all sorts of ideas, from making an animation to using trendy b-boys as models. I added my two cents’ worth.

“Cup noodle ads should be different from regular noodle ads. What’s the best thing about cup noodles? Answer: you can eat them anywhere, and there’s no hassle. Let’s show climbers on a Himalayan peak. They’re about to reach the top and blizzard hits, and they have to hole up in their tent. It’s bitter cold, the climbers are trembling, their teeth are chattering. They open a can of food, and down their stomachs it goes. Then the Sherpa melts snow and boils water. He searches his backpack, takes out the cup noodles, adds boiled water, and digs in. When the storm stops, he guides the climbers the rest of the way to the summit.”

I saw some heads nodding. Even the team leader, who always came up with the most negative response, didn’t shoot me down this time. The conference room, normally a beehive of heated discussion, fell silent. That can only mean one of two things: the idea is either a total bust or a total blast. When it’s the former, people never look away from the speaker. Their expressions almost always contain a hint of cynicism, but they disguise it with sympathy. But if the idea’s a blast, they try to avoid eye contact because they don’t want me to see the jealousy that’s spreading in their hearts like a deadly poison.

“The cup noodles expedition . . . It could work if we made it funny,” Sauna Pak reacted. No one objected.

But just when I was about to pat myself on the back, guess who opened his mouth.

“As all of you must know, there’s a peak called the Jungfrau. It’s one of the toughest climbs in the Alps, the rooftop of Europe. It’s 4,156 meters high and snow-covered year round. You can tell from its nickname, the Virgin’s Shoulder, that it rarely gets conquered.”

Everyone looked puzzled. Hadn’t he said he was just an observer? Why the hell did he bring up the Jungfrau out of the blue? I guess the Midas of this industry still hasn’t figured out how things work here. They tried not to show it, but I bet this thought was on everyone’s mind. But he ignored our bummed-out faces and carried on.

“. . . Let’s show a Korean man visiting an igloo, and the Eskimo man bringing out the cup noodles. Our audience sees them having cup noodles together in the igloo. We’ll play the same concept in Niagara Falls, Machu Picchu, the Great Wall of China, and even in the Eiffel Tower.”

“There’s an observatory at 3,454 meters where you can see the Virgin’s Shoulder, and guess what the best-selling snack is. You got it! Cup noodles. They stock them because of the demand from Korean tourists, and now, as you all know, they’re popular among westerners, too, even though they aren’t so used to spicy food. So you can see there’s still a big market for cup noodles. If we can show that cup noodles are doing well overseas, maybe we can boost domestic demand. I tell you what: let’s run an ad campaign based on a message like ‘Share our spicy taste with the world.’ You know, the Eskimos have a tradition: they offer the very best to friends who visit them. Let’s show a Korean man visiting an igloo, and the Eskimo man bringing out the cup noodles. Our audience sees them having cup noodles together in the igloo. We’ll play the same concept in Niagara Falls, Machu Picchu, the Great Wall of China, and even in the Eiffel Tower.”

And then he made up a slogan right then and there: “Sharing our spicy taste with the world anytime, anywhere!”

It didn’t matter what he was actually saying. We were just blown away at whatever he said. It was like watching an ad clip right before our eyes.

“Bravo!” someone shouted. Others applauded.

“You nailed it—the tendency that Koreans just go head over heels for anything that draws attention in the West, no matter how small or trivial it is.”

“You’re creating a brave new world in cup noodle ads.”

“‘Roar in the East and strike in the West,’ kind of strategy.”

“Can I tag along for the overseas shoot?”

“Machu Picchu, here we come!”

By now it was a free-for-all. His face still wore the same smile.

“Guess how much a pair of the most expensive chopsticks in the world is?”

Look at that. That’s what you get when you give a man the right kind of attention.

“Well, what happened was, Korean tourists started asking for hot water and at first, the people at the Jungfrau observatory provided it free of charge. With the water, the Koreans were making something to eat and enjoying it like there was no tomorrow. The quick-witted Swiss saw this as an opportunity and began selling cup noodles. But no one bought them: they only asked for the hot water. So the Swiss began selling hot water. Some people forgot to bring chopsticks, so they started selling that too. Three euros for hot water, and one euro for chopsticks. And what happened? The Koreans no longer brought cup noodles.” Laughter burst out from the gathering. And before I realized it, I asked him a question.

“Isn’t the Jungfrau actually 4,158 meters, not 4,156?”

The laughter stopped as if I’d ordered everyone to do it. No one made eye contact with me. All eyes were on him, awaiting his reaction. My gaze and his made a tight clot in space, and then his smoldering gaze provoked something that’s been sitting in the deepest part of my memory. I could have sworn I’d seen those eyes and that look in the past.

I still can’t forget the look of fascination and vigilance flickering in the eyes of the students when my new principal introduced me. And especially the eyes of a boy sitting in the far corner by the window. They were the eyes of a boxer staring down his opponent while the referee gives instructions. The penetrating glare beaming from his slanted eyes frightened me. It was the hostile glare of a predator toward an interloper, and of a student who envied the compliments he didn’t receive. I felt the eyes burning and then stabbing me like an icicle in the darkest and the most fragile recess of my heart. Those eyes belonged to the student who apparently had the highest grades in the school before I arrived. His name was T’aeman, Kim T’aeman.

“You have quite the memory, Mr. Ch’oe. Yes indeed, the Jungfrau was 4,158 meters. But now that the summit glaciers are melting it’s two meters shorter. Greenhouse effect, you know.”

The smile was still there, a shrewd one in which the corners of the mouth point slightly upward.

“It’s a pleasure to work with you, Director,” someone proclaimed. Someone else rose from his seat and clapped like he was welcoming a victorious general back to Rome. The once-pulled-up corners of his mouth that could’ve come from sardonic thoughts suddenly relaxed and he couldn’t have looked more serene than now. I craved something sweet.

* * *

His cup noodle proposal mesmerized the clients. Needless to say, he was the one who gave the presentation. Some people had doubts about the high cost of shooting the ad overseas. But not the clients—we were told later that they were delighted, especially with the slogan “Sharing our spicy taste with the world.” The clients bought into his ad campaign, which he’d dubbed the World Tour Series, and that meant a contract for at least six seasons. He’d hit the jackpot.

Complaints about bringing him transformed into praise for his outstanding ability. His age, which had brought complaints of outrage at his recruitment, became a testament to the company’s flexibility. The veiled negotiations piqued kitschy imaginations that generated a succession of success sagas: the CEO had offered him control of the company. The CEO had sought him out no less than seven times. The CEO had met him by chance when both were benighted on Chiri Mountain. And the best version was that he would soon become the CEO’s son-in-law. These unverified rumors cast his ascendancy in an even brighter spotlight, precisely because they were unverifiable. He swept into every meeting like a conquering hero. People were overwhelmed at first, but felt more comfortable as time went by. In meetings, he listened to everyone’s ideas before offering his own, which became pivotal and then final and then bingo—production was based 100 percent on his idea. The ads themselves ended up exactly as he’d proposed them and that included not only the basic thrust of the ad but even details such as the models to be used. In no time, he’d gained full control of the company.

A company dinner was held to mark the extension of the cup noodle contract, but it turned into a flattery contest focused on you-know-who. Even the people who had freaked out when he was appointed a director complimented him on his wits and his eloquence. The same ones, mind you, who last I knew were saying that I was the clever one, that I was the one with the idea bank in my head. The women staffers were dying to at least make eye contact with him. Even Misŏn downed a mug of beer he poured her, and then returned the favor. With me, she always fiddled with her beer instead of drinking it, blaming her face for flushing after just one glass of the stuff.

People talked about his fancy education: a bachelor’s degree from an Ivy League school followed by an MBA. He said he’d worked a short time for a consulting firm before making a career change to advertising. To him, it was creativity over money. When asked why he’d decided to come back to Korea, he said, “I saw a billboard in Times Square for a Korean company, and it touched my heart. I decided I wanted to sell products that were made in Korea.” Someone nodded and someone else applauded. And then Chŏng, our new copywriter, spoke up.

“My cousin goes to the same university you did. He tells me it’s crazy the way they haze the freshmen. Was it like that when you were there?”

Our hero had a sip of beer before answering.

“Well, I can’t really say. You see, I had social anxiety disorder all through college. I used to stay in my room all day. No way I could have sat through all my classes. They used to call me the Ghost. I’ll tell you how bad it was. One day I went to class—it was a course I had to take for my major—and when the professor saw me, he said to tell Steve Kim he was going to flunk him if he missed another class. I thought he was joking, but then I realized I was the only one laughing—no one had told him that I was Steve Kim. I felt a chill all over me. Maybe I really was a ghost. It was scary—I thought I was going to cry. The very next day I walked into a psychiatric clinic and started getting treatment.”

Silence came over the room. It was like we’d all been doused with cold water.

“I’m sorry I asked,” said Chŏng in a limp tone.

“It’s all right. That was way back in the past. Just remember, it’s not much fun to hang out by yourself.”

Everyone’s face softened.

Next it was Kang’s turn. She was part of the design team and liked to brag about her education overseas.

“I heard you moved to the States when you were in grade school. But I can’t believe you speak Korean so well. I left after high school, and my Korean still got so rusty I had a hard time when I got back.”

Kang drove a Mini Cooper and accoutered herself only with luxury handbags like Louis Vuitton or Prada. I could see Misŏn’s face clouding over. She occasionally grew furious because Kang treated her like a country mouse. Unfortunately for Misŏn, most of the young women here were not much different from Kang. When you’re affluent you don’t get a job just to make ends meet. And these women spend their paycheck decorating themselves. They’ll get married if a man with cash and power comes along, but a real-life, run-of-the-mill marriage? They would graciously decline the offer. A career woman who gets to enjoy the good things in life, making her life better with her job—sounds good, doesn’t it? It was these women and their discretionary income that advertisers targeted in the 1990s. But that strategy was yesterday’s news. The reason being that the career woman’s lifestyle is no longer a fantasy—it’s a reality.

“They’re a different breed. The cream of the crop. They even smell different.” Sauna Pak never got tired of reminding us that the current generation of employees, hired after the company had gone through a period of rapid growth and was now moderately successful, had come from good families and good schools. They drove to work in luxury import cars they’d already owned when they were hired, and were fluent in English of course and another foreign language besides. Within her cohort, Misŏn’s rural educational background stood out in contrast with the urbane, prestigious, international background of the others. So much so that when she was hired, people suspected she had a sugar daddy looking out for her. People wondered if her father ran a small-city construction company, or was a big investor in a private moneylending business, or a close relative of the company CEO, but such rumors also proved groundless. Her father was just a city hall civil servant in a small city. When people found out about her background, the company gossips began to skewer the CEO’s eccentric interview technique. Being a former caretaker of a cabin on Chiri Mountain, our CEO liked reading faces and palms, and learned the birth hour of candidates he interviewed. And with Misŏn, some people actually saw him nodding and declaring she was destined to make diamonds and gold wherever she went. Apparently, she already has five bank accounts.

“My mom would always make me speak Korean at home,” he replied with a nostalgic look.

Everyone nodded.

I remembered how T’aeman’s mother, who worked at a foreigner bar near the shipyard, would always mix in English words. “What’s your father’s chab?” or “What’s your ho-p’ŭ for the future?” she would ask me.

She was known as one of the most beautiful women on the island. With her creamy complexion, come-hither eyes, and irresistible charm, she could make even the notoriously brusque Englishmen open their wallets. But T’aeman in no way resembled her. People would say various things about his family. There was no father in the picture, and no one believed T’aeman’s claim that his father was a crewman on a deep-sea fishing vessel.

“Which elementary school did you go to?” I asked.

He blinked before he answered. “I’m afraid I don’t remember—I wasn’t there long enough to remember. When I got there, I literally lost my memory from jet lag.” He shrugged as he said “jet lag.” “But I can assure you, Mr. Ch’oe, that you and I are not from the same school. You can trust me on that.” Contemptuous laughter bursted out everywhere.

In between bar hops after the dinner, I grabbed Misŏn’s hand and we slipped out to one of our favorite cafés. I was so thirsty I chugged a bottle of Budweiser.

“You know, he took my idea for that ad.”

Misŏn looked at me like I was a lunatic.

“You dragged me here just to tell me that eating cup noodles in a special place was your idea?” There was a slight but noticeable pinch at the end of her sentence.

“You wouldn’t understand because you weren’t there.”

“So what? I have sources, you know. How can you compare a snowy mountain to the North Pole? And our director’s point is to have cup noodles with a foreigner.”

“Big deal. Snowy mountains, North Pole—same difference. And it’s not the location but the occasion that makes my concept stand out. Enjoying cup noodles in a special place you’ve never been, that’s the feel we want to get across, okay? And while we’re on the topic of exoticism, my Sherpas are just as exotic as his Eskimos. The bottom line is, Steve Kim stole my idea.”

“The point our director is trying to make is that it’s the Eskimo tradition to offer the very best to their guests. That’s how much the Eskimos treasure cup noodles.” Misŏn looked me straight in the eye as if it was her business to defend our esteemed director.

“Maybe he didn’t copy me word for word. But his Eskimo concept is only a variation on my idea.”

“I hope you didn’t tell others about this,” Misŏn said in a you’re pathetic tone.

“You think I’m exaggerating?”

“Why should it be a problem to get inspiration from your idea? Isn’t that what the concept meetings are for?” She didn’t back off this time, which was so unlike her.

“The problem is, everyone’s fawning over Steve Kim as if it all came from his head.”

“You’re just upset because you didn’t get the credit.”

When she said that, I felt the blood rush to my head. I took off my jacket.

“The point I’m trying to make is not that I’m feeling sorry for myself or I’ve been treated unfairly. I’m just trying to tell you the truth. No way am I complaining for recognition—I’m just asking you to open your eyes to the truth. When the truth gets compromised, the only way you can make up for it, the only consolation you can offer, is the truth itself!”

People were giving me looks. I must have been talking too loud.

“Okay, I get the message.” Suddenly she was docile. She liked it when I talked like this. I don’t know why, but in her presence I’m the man with the gilded tongue. Her eyes glimmered with admiration—the look that makes me feel like I am the chosen one, a full revelation of reverence and respect toward what she doesn’t possess. The same look that I could easily spot at Town G.

“Don’t you think there’s something fishy about him?” I said, acting as if this thought had just occurred to me.

“What about him?”

“I don’t know. It’s like he’s avoiding everything about his life in the U.S. Especially his school life.”

“He’s probably being humble. If it were someone else, he’d be flaunting it. You know Koreans, they’ll talk about their one-time overseas trip for the rest of their lives. But when our director came clean about his weaknesses, all my reservations about him vanished. I can’t imagine it would be easy for someone so successful to make such a confession. At first, I thought he was a man of ambition blinded by success, but I find him so genuine now. An antisocial freak who turned into a MarComm prince. He’s amazing.”

I was starting to regret having spilled my feelings, but God help me, I had already crossed the Rubicon.

“Do you think it’s actually possible he forgot the name of the elementary school he went to?”

“It could happen, believe me. I don’t always remember my cell phone number or my address. Who knows? Maybe he really did go blank from jet lag?”

“You’ve got to be kidding! Jet lag? You’re not making any sense.”

“Maybe I’m not. By the way, why are you so furious every time we talk about our director? Are you jealous?” She looked at me with a perky smile.

“Jealous my ass! There’s no such word in my dictionary. And what’s with ‘our director’ this and ‘our director’ that? You don’t even work under him. You know, when Steve Kim gives you a drink, you down it in one gulp—I saw you. But when I give you a drink, you just go through the motions like you’re in an ancestral rite—you haven’t even touched that shot glass. It’s like your director is giving you sugar and I’m giving you licorice.”

“You are definitely jealous.”

When I saw her grinning unperturbed, I felt a cold shiver all over. Thoughts of despair and loss of direction, pressed down on this heart of mine–I was about to start something that had no chance of success.

* * *

Up rose you-know-who in triumph and off he flew, beyond the reach of my doubting hands. He was shining brighter than ever. At work, he was talked about at every opportunity.

“Wow, he’s going on seven for seven. He hasn’t lost a single project to a competitor.”

“I heard they had a fit at his last company when he came to work here. Apparently, the owner followed him around for a week sweet-talking him—bonuses, stock options, the whole works. But he ditched it all to come here, which probably means our CEO did promise he could run the company after him.”

“That’ll make him the youngest CEO in the industry. I guess it’s only a matter of time.”

He was becoming a legend in his own time. The brighter the spotlight on his achievements, the more suspicious I grew. For one thing, it didn’t make sense to me that he’d ditch a successful career in a world-famous global consulting firm like a used Kleenex to come here, all on account of full-blooded patriotism. These days, people were doing exactly the opposite, quitting their jobs and crossing the Pacific Ocean for personal development and new challenges. So, you-know-who was doing it all backward. Did he really expect anyone to believe he wanted to sell things that were “Made in Korea”? How much more ridiculous could he get? When it comes to marketing, we cross borders all the time. We bring in foreign capital and use a foreign workforce to make the products, and we advertise the products with foreign models. We even prefer copy written in foreign languages. And how about his veiled past? I just couldn’t understand why no one saw the faults that to my eye stuck out like huge pillars. Whenever I tried to stir up Misŏn by mentioning him, she treated me like I was the lunatic. His unconvincing motif for coming back to Korea had transformed into an absurd Zionism and his murky past ironically contributed to this myth.

But I had to admit he was good. You could almost see the sparks shooting from his head, especially when he ran up against an obstacle. Recently, we were demonstrating our new milk ad. On an early morning starting a new day, a woman in a jogging suit is running downtown. A moment later, she sees a newspaper and milk in front of her doorstep. She wipes the perspiration from her forehead, twists the cap from the milk bottle, and drinks straight from it. “Get a head start with a fresh bottle of milk”—the copy I wrote—appears on the screen.

But the client wasn’t exactly pleased. “The model has a flat chest. It’s a milk ad, for god’s sake.” And when he left, grumbling like he’d stepped into a downpour, everyone involved in the ad left too, like they were being carried out on an ebb tide.

“They’re big enough for me,” Sauna Pak commented. “What’s with the old man and the boobs?”

When everyone giggled, Steve Kim exploded.

“How can you laugh when your client says no? And you guys call yourselves pros? You have no shame!”

Pak’s face flushed as if he’d just stepped out of his beloved sauna. I couldn’t face him.

“The model’s bust size shouldn’t have anything to do with the sales,” I murmured.

“Mr. Ch’oe, your job is to sell the milk ads, not the milk itself!” The tone of Steve’s voice escalated. “Let’s do a retake. Add more volume to the model’s breasts, then reshoot.”

“Director, um . . . the model is in Australia now, on a film shoot,” said Chang, our creative director, her voice shrinking. Here was an obstacle.

“You let her go before the client okayed the ad? What the heck is wrong with you? Do you think this is a college club or something?”

I had never seen him this upset. Here was a dilemma. A heavy silence occupied the conference room. He lapsed into thought, but only for a moment.

“We’ll do a CG,” he announced. “Put in a request to the production department. Tell them to fill out her chest and create a jiggling effect when she runs . . .”

“But . . .” Chang looked baffled.

“What’s the problem?”

“Well, she’s trying to transform her image, she wants to steer clear of the sexy image she has now, so I wonder if it would make any sense to . . .” Chang’s voice faded as she awaited Steve’s reaction.

Steve responded syllable by syllable, as if instructing a child: “Call the ma-na-ger and tell him the cli-ent is con-si-der-ing re-plac-ing her.” And then to himself, “Transformation my ass.”

On the way out he turned to me as if he’d just remembered something. “Ch’oe, I want some new copy. This one was too weak, you know. Can you finish by tomorrow morning? The rest of you, let’s grab a drink after work.”

“On you?” A cheerful voice came from the crowd.

“Of course.” He couldn’t have sounded more cheerful.

That evening I sipped milk and tried to squeeze out new copy all by myself in the empty office.

“Milk?” Miss Kim said as she plopped a black plastic bag on my desk. She was the administrative assistant who handled Xeroxes, faxes, and all the other unclassified, miscellaneous tasks. The bag was filled with bottles of the milk we were advertising.

“What’s with all the milk?”

Compliments of Steve Kim, she said. It was supposed to encourage me to write up a snappy slogan.

“Do you need anything else?” said Miss Kim, unable to contain her sneer.

“Just some lactase, please,” I answered with a fake smile.

But doing my work was the last thing on my mind. I couldn’t help but scowl at the monitor and fiddle with the mouse. When I came out of my trance, I found myself searching for the homepage of the school he said he’d graduated from. I even typed in “autism,” “ghost,” “director,” and “Steve Kim” in the search box. As I stared at “Steve Kim,” I smacked my forehead. Steve Kim couldn’t be his real name. Since he wasn’t born in the U.S., he had to have a Korean name. What an idiot I was—I should have thought of that in the first place.

The next day, I lured Misŏn out for lunch with an offer of spaghetti. Since it’s her dream to go to Venice, she goes crazy for anything that’s Italian. Come to think of it, even the name of the restaurant was called Venecia. She had a big smile on her face as she browsed over the menu. The dishes were pricier than I thought. She ordered seafood lasagna and spaghetti vongole.

“What’s up with you today? You won’t even grab my hand if we’re within sight of the office, and here you are asking me out to lunch?” she pouted.

“Do you happen to know Steve Kim’s Korean name?” No beating around the bush for me.

“Our director? Hmm, how should I know?”

It was not quite the kind of response I was looking for, but I couldn’t back off just yet.

“Aren’t you curious what his Korean name is?”

But she wasn’t that easy to get.

“Why is it so important to know his Korean name?”

“Afraid to find out because this could kill your fantasies about him?”

I nudged her to stir her emotion. It worked like a charm.

“Nonsense. I’m not a high school girl going through puberty!” She became enraged. It was an opportunity to dig in deeper and I grabbed onto it.

“Didn’t he give you a copy of his bankbook for his paycheck? That’s where you’ll find it.”

This thought had come to my mind during the wee hour of the morning while I was scribbling for the milk ad. Thank god bank accounts can only be made with real names! When I thought of that, I almost got up from my desk and shouted, “Yay.” After she finished processing her thoughts, she asked me, “What are you cooking up now? What the hell are you trying to prove, anyway?”

“Oh, just curious,” I said, but it sounded like a poor excuse even to me. Just in time, the food came.

“Director!” exclaimed Misŏn

There was you-know-who, on his way out, looking in our direction. Up sprang Misŏn, and to my inquisitive girlfriend’s greeting he explained that he hadn’t been able to find a table. Was he by himself? she asked. He nodded. And suddenly Misŏn was all smiley.

“Come sit with us,” she suggested.

“Thank you, but I wouldn’t want to be a nuisance,” he said politely.

“No, not at all.” And then to me, finally, “You don’t mind, do you?”

Speak of the devil. I barely managed to suppress the words. “Please have a seat, Director,” I said as I pulled out the chair next to me.

Misŏn pulled her chair right up to the table and asked, “Have you ever been to Venice?”

“Venice?”

“Venecia, I mean.”

“Oh! Venecia. The city that dates back to the fifth century B.C. It was built off the mainland by people who fled from Attila, King of the Huns. You know who Attila the Hun is, don’t you? He was the conqueror from the East who put everyone in Europe in fear.”

”Wow, amazing. You’ve been to Venecia too. I should visit before it sinks into the sea.”

“No need to worry,” he chuckled. “It’s a UNESCO world heritage site. I’m sure they won’t let it sink. As a matter of fact, they are preparing a big-scale project to stop the subsidence. They are building a breakwater that can control the flow of incoming seawater. To raise this tremendous amount of money on the construction, they’ve even raised the fee for using a public toilet big time. They charge you one euro for using the toilet, can you believe it? They say it’s a type of environmental tax. They sell water to you and tax you for passing it out. It literally is the city of water.”

Taken by his mind-boggling eloquence and encyclopedic knowledge, her jaw hung loose on her face.

“You should probably order, Sir,” I cut in.

“Misŏn, when you eat garlic bread, you need to dip it in olive oil and balsamic vinegar for an authentic Italian taste.” And then, ignoring the menu, “Waitress, I would like to order a margherita pizza and gnocchi. And bring some balsamic vinegar, the six-year-old.”

“I’m sorry, sir. We only have three-year-old,” said the waitress.

“Oh well, I guess we don’t have a choice. But the six-year-old is the best.” While he tut-tutted in disapproval, I dunked my garlic bread in the spaghetti sauce.

Later, over coffee that came with the meal, I asked you-know-who what he thought of my new copy.

“Copy?” he replied as if he had no idea what I was talking about.

“The copy for the milk ad!” I raised my voice in spite of myself.

“The milk ad? Your copy was fine. Why, did you come up with something new?”

“Yes. Just like you told me. By this morning. Don’t you remember? I stayed late and worked on it all night.” I couldn’t bring myself to tell him I’d drunk all of his milk.

“Did I? Well, good work. I’ll have a look at it when I get back to the office. Misŏn, drink your coffee before it gets cold. The best coffee comes from Colombia.” He avoided eye contact with me as he said this. Something steamy soared from my heart. I plopped sugar cubes into my coffee.

He left by himself saying he had to drop by somewhere. Misŏn and I walked toward the office building together.

“Strange,” I mumbled.

“Now what?” Misŏn asked.

“If he’s been in the U.S. long enough, he should be more familiar with Venice than Venecia.”

“Right, the English pronunciation of Venecia is Venice.” For once she agreed with me.

“Right?” I was so glad that my voice went up.

“So?” She seemed puzzled. Uh-oh, she didn’t get why I was so happy.

“When you asked him whether he’s been to Venice, he didn’t get it, remember? But when you said Venecia, he understood.”

“So what?” She gave me a cold stare. When I couldn’t reply right away, she jumped right in. “What the hell are you thinking? No, no. When you start doubting people, it snowballs. You just can’t stop once you start. So, are you accusing him of faking his identity? Forged, huh? Our company is not stupid.”

“Some professors have fake diplomas.”

She didn’t seem to know how to respond to that, so she didn’t. Even though there were only two of us in the elevator, I whispered in her ear, “Don’t forget about what I asked you.” Instead of answering, she gave me a dirty look.

* * *

The next afternoon, she messaged me.

Break your fast yet?

Our code for “the coast is clear? okay to chat?”

Try fasting for three days yourself.

That meant it was okay.

The name of our esteemed director is . . .

“Our esteemed director”—that was a nice touch.

Come on, out with it.

Kim Hyŏnbin

I was expecting a hayseed kind of name, and Hyŏnbin took the wind out of my sails. It was a smooth, urbane Korean name.

That name gives me the creeps!

It’s a kind of name you would see in romance comic books! I like it much more than Steve Kim.

Romance comic book my ASS!

The male character that usually gets hooked up with the female character through a pen pal has names like this. Hyŏnbin!

Will you stop? You are grossing me out. . . . Hey, now I remember!

Why stop in the middle of a juicy scene? You want to change the character?

In the darkroom of my head, I tried to collect the scattered light from a classroom scene that happened around twenty years ago on a summer day during my first year in high school. Officially, it was summer vacation, but everyone came to class for supplementary classes and optional study sessions. While we were studying, the math teacher who was on night duty that day came into our classroom.

“Who the hell is Kim Hyŏnbin?”

He was holding a pink envelope. Of course, no one raised his hand. There was no one with that name in the class.

“Isn’t this class two? Strange. It should be right.”

“That’s mine,” came a low voice from in back. It was T’aeman. He walked timorously toward the front door of the classroom.

“What took you so long? Wait a minute. Aren’t you Kim T’aeman?” the math teacher asked as he pushed up his glasses for a better look.

“I’m sure that letter is for me.”

To get the letter, he confessed that Kim Hyŏnbin was his pen pal name, but instead he was put in charge of cleaning the bathroom for a week as a punishment and didn’t even get to read the letter. After this incident, whenever the math teacher saw T’aeman, he teased, “Hyŏn Bin, do you still write letters these days? Or too ‘lazy’ to write?” People always made fun of “T’ae man” because his name sounded the same as “lazy” in Korean, so T’aeman had always been unhappy about his real name, to the point where he would forge his name to his pen pal. Maybe Steve Kim is really . . . I shook my head hard to get rid of the thought.

As soon as I got off from work, I rushed home and took out the high school yearbook. T’aeman was not in the album. I started smoking again, which I had quit, and tried to remember the past. After I moved in, the first place was no longer his. There, at the very top place of the list of honor students posted on the wall, next to the main gate of the school, was my name, always. T’aeman and I never spoke to each other. Even though he was known to “hang out” after school, he seemed to be quiet in class. Whenever I passed by him during recess or lunchtime, he had his nose buried in a comic book, giggling. It was always the same comic book, and one time, I saw him holding it upside down.

I, for one, spent most of my time studying so I had no time to make any friends. Frankly, life on an island where there was no one I knew was only a small price to pay to step up to a bigger world. On that gusty island, I was as lonely as a shirt suspended all by itself on a clothesline, but I found solace in books till late at night to fight loneliness. The school was trying really hard to step up to become prestigious, which I give it credit for, but when it came to academic performance, it was no match for my former school. There, my rank went up and down within the first five, but here, I was always ranked number one. T’aeman was ranked number two, but he just couldn’t seem to catch up. Instead, his grades started to drop. Compared to how he did before, his falling grades made him look like a failure. He never did raise those grades, never recovered his fame, and then in the darkest days of fall in his second year of high school, he left the island without letting anyone know. Although he went rambling on here and there that one of the shipyard engineers had taken a liking to his mother and invited them to England, the real motive for their escape was as mysterious as the fog. Others said they had to leave abruptly because either his mother had been involved in a relationship with a married man, or T’aeman’s father had found out where they were living, but some people really thought he went to England because he had actually submitted a withdrawal request to the school.

I looked through the old yearbook and finally found T’aeman’s face in a group picture from a school trip on our first year. There he was, in the back corner. He had slanted eyes, a snub nose, an angular jaw, and a protruding chin. His skin was dark, presumably from the sun, and covered with pimples. He was crossing his arms and had a bored look on his face, as if to show that he didn’t belong there, and he didn’t care about anything that was happening around him.

At our next meeting, I studied you-know-who’s face thoroughly. Well-defined eyes with double-creased lids, aquiline nose, sleek jawline, and not a single blemish on his smooth skin. Urbane and sophisticated, he looked like he popped right out from a photo shoot for a men’s magazine. He exuded the confidence and generosity of spirit you can only see in a man whose future was already secure. If there were someone who had everything T’aeman didn’t have, it was him. That’s how much they had nothing in common. The distinction was so clear that it felt unnatural.

“Ch’oe, is there something on my face?” He swiped his face with his hand.

“No, not at all. It’s just that your skin is so flawless,” I scratched my head and said the first thing that came to my head.

“Ch’oe, something tells me you’re being too hard on yourself lately. Your face looks puffy. Why don’t you go see a dermatologist?”

“Dermatologist my . . .” Just as I was about to say “ass,” the women in the conference room all frowned.

“You know, Mr. Ch’oe, nowadays, even men need to take care of their looks. Beauty on the inside? That’s something only the finalists in the beauty pageants should say. Who’s to argue inside or outside when it comes to beauty? Besides, we MarComms are the creators of images. So, please understand that when you look disheveled, it only proves that you are too lazy to take care of yourself.”

The next day, I went online and found a beauty clinic for men. It was a “total” clinic, offering everything from skin care to plastic surgery. I skimmed over the bulletin board and was surprised to find out that a lot of guys were interested in plastic surgery. I sent a text message to Misŏn to ask if skin care had any benefits, but the reply I got from her was, “Hello, old bachelor, you must be out of your mind.” To that, I almost replied, “Who are you to judge whether I deserve to get it or not?” Instead, I took a chocolate bar from the drawer and took a bite.

* * *

I got involved in a car ad proposal. We’d been asked by a leading automaker that we never had a chance to work with. You-know-who brought it in. A car ad was like the mother of all big fish. Everyone in our company was so excited because it was such a rare opportunity. If we won this bid, it would make us bigger and stronger. The car we had to make the ad for was a new SUV with a touch of the classic elegance of a sedan. According to the analysis from our marketing team, the current SUV market was already saturated, with young users being the main drivers. To penetrate the market, we had to strengthen the relationship with the highly loyal middle-aged customers and create a new demand at the same time. We had to come up with a concept that could express both the sportiness of an SUV and the luxury of the sedan. We had to combine the two opposite, oil-and-water-like images, brio and class, into one killer ad. Being such an important project, the company created a special team. You-know-who became the leader. It was nothing new to create a project team for a bid that was big and important, but it was unconventional to designate a director as the team leader. So of course there were complaints, mainly from the older employees.

“I know Steve Kim’s got the talent. But with all due respect, when the director becomes the team leader too, where does that leave us? Are we supposed to pack our bags? Regardless of the organization, the employees deserve professional courtesy.”

“Isn’t it also weird that he’s still attending every meeting? In the beginning, it was understandable. He had to do what he had to do to catch the flow. But why is he still ‘catching the flow’? Maybe he’s sorting out which ones to lay off, huh? I guess the buzz about the extensive layoff wasn’t a piece of baloney after all. And you know what? He was in charge of corporate restructuring for that consulting firm he worked for.”

“Corporate restructuring?”

“Trimming the fat. The CEO has no experience in this area so he’s hired a hit man to help him out.”

“He can’t even remember the name of the elementary school he attended. No trespassing, huh? If he’s playing the mysterious magician, then he’s not an average Joe. The young generations are just too smart to beat . . .”

Everyone’s eyes glided toward me.

“I just asked which elementary school he went to, that’s all. Nothing personal. I just thought I’d seen him before . . .” I even put up my hands and made a hand gesture.

“Nobody said anything.”

Someone smacked his lips and someone rubbed his belly. Everyone was waiting to see how Sauna Pak would react, but not a word came from his mouth.

The suspicion I couldn’t tell anyone about became tougher and tougher to scrape off, like a piece of gum that got stuck on the bottom of the shoe.

You-know-who treated the entire project team to lunch at a Japanese restaurant near the office. Calling for everyone’s commitment to this project that meant so much to the company, he ordered sake and even personally served it to each and every member of the team. When we finished eating and making our way out of the tatami-floored room, I noticed a pair of brown Ferragamo shoes. Only the right shoe had a thick cushion in it. They were you-know-who’s. He took out a shoehorn from his pocket and used it only on his left shoe. I almost exclaimed. I knew only one other person who had different-sized feet—Kim T’aeman. How could I ever forget? He was the only person who wore Nikes in class, which were expensive even to look at, but the back of one of his shoes was always snapped in. T’aeman’s left foot was also bigger than his right foot. Come to think of it, you-know-who was also was a lefty, just like T’aeman. I felt dizzy and nauseous as if I was up somewhere high, then my palms became sweaty and my chest felt tight. I was hallucinating due to all these coincidences, and I couldn’t shake it off. Every coincidence seemed to reveal some kind of truth about his identity that no one else in the world had yet to find out. That whole day, I couldn’t concentrate. The suspicion I couldn’t tell anyone about became tougher and tougher to scrape off, like a piece of gum that got stuck on the bottom of the shoe.

The first time T’aeman spoke to me was around the end of our second year’s summer vacation. We met at the deck of the ship, which I had gotten on to go back to my hometown during the real one-week-long summer vacation. He recognized me first. As we went up a grade, I didn’t get much chance to see him because we were placed in different classes. He pretended not to know me, even when we ran into each other in the hall. But he was being all nice to me this time, like he had been like that all along. Next to him was a girl. She was fair-skinned and had big eyes. She was attending a girls’ high school nearby and had come from Seoul last year with her father.

“Glad to see you.” I was about to bow my head but didn’t, which made me look awkward.

“You are the one who the school brought to enter a student in Seoul National University. What an honor. Let’s be friends.” The girl from Seoul looked at me straight in the eye and offered a handshake.

* * *

When the ship docked at City B, the girl from Seoul invited me to join them for a movie. When I hesitated at this unexpected gesture, T’aeman cut in and said it would be more fun if I joined. That girl, whenever our eyes met, smiled with her eyes. When she did that, something that had been piled up in one corner of my heart crumbled. I don’t remember the title of the movie. She smelled so good, and it was nothing like I had smelled before. The thought of going back to my house was long gone. The whole time the movie was playing, T’aeman’s arm was wrapped around her shoulder. From time to time, his hands played with her hair.

After we came out of the movie, we went to a beach. There, T’aeman and the girl changed into swimming suits they had brought with them. I didn’t have one, so I lay under a parasol and watched them play in the water. All over my body, I felt the nail in my heart becoming loose under the beach parasol where the sunlight shined down like crumbled pollen. It had been screwed in tightly ever since I became old enough to know the world. My eyelids were heavy because of the sun, or the sea. The glimmering white yacht, cruising toward the horizon at the end, seemed so far away like a dream.

“It’s an awesome yacht,” T’aeman plopped down next to me and said. T’aeman sent a gentle glance at the yacht and babbled on about some movie. He talked about jealousy, revenge, and murder, the dark fate of a young man who couldn’t fulfill his dreams because the burden of his tattered background weighed down his shoulders. He was being all gloomy when he talked about a young man who tried to change the course of his fate but became stranded all because of a small mishap. He also told me about the last scene he could never forget. About the corpse of his friend that got caught up by the anchor and came up on the surface just at the moment he was about to get everything in his hands. He said he even shed tears when the corpse got caught by the anchor and rose up. What he said became a vivid image and spread before my eyes, and the image was as lively as the cloud that roamed above the blue sea. I felt like I saw the movie just by listening in. At the beach where we watched the glimmering yacht melt into the cloud hanging on the horizon, he also said, “you always have to check your anchor before you set out.” I heard some native Indians believe when they carve in the shape of what they fear, they will be set free from it. It was a questionable saying. For some reason, a part of my mind became darkened as if shade came over me. T’aeman’s gloomy voice was abysmal like the water spray on the yacht’s path. As my eyelids weighed down, I fell into a deep sleep. Much later, I also got to see the movie he talked about. In the last scene, the corpse came out not because of the anchor but the screw. T’aeman was wrong.

The days were as hectic as hell, because I had to do a lot of work for the car ad. Meetings after meetings, nights sacrificed for work. My suspicion poked its way up whenever I saw you-know-who’s face. The suspicion that didn’t get enough sleep opened its eyes wide and sniffed like a beast looking for its prey. Don’t you want to find out what kind of truth lies sealed under that smooth mask, and what his cheerful and clean-cut smile is hiding? Are you sure you are not curious? the dwarf inside my head whispered. The suspicion that I couldn’t dare to express was fertilized by the forced silence and rooted all the way down to the remotest part of my soul. For my own sake, it would be better if he was not T’aeman, and all this was happening in my head. Therefore, the more evidence I saw that made my suspicion grow stronger, the more I wished he wasn’t the person I knew before. I was practically caught in a trap of my own making, which was therefore more life-threatening.

“Why are you clenching your teeth like that? Is there something wrong?”

I was even asked as much, while I was staring into my computer. By the afternoon, I became completely exhausted like someone who repetitiously went back and forth from the cold tub to the hot tub. Both my body and my soul felt like they weighed a ton, as if my ankle was fastened with an anchor. I started ignoring Misŏn’s text messages. At one moment, I would fall into the deepest sadness of losing everything. At another moment, I would be overwhelmed by a fury that would be fierce enough to make everyone my enemy. I was devastated from seesawing between these extremes of sadness and fury. I faced the mornings absentminded on the sofa, and dozed off at my desk in the afternoons. Nightmares invaded between sleep. When I roll the anchor in, the swollen corpse with his face would come up. When the bluish, putrefied skin was peeled off the face, T’aeman appeared with a smile. Sometimes, it was my face that was smiling.

This time, let’s make transformation our concept. It would be a representation that this car has both the elegance of the sedan and the energy of a leisure car with the theme of transformation. You all know that recently, a movie about transforming robots gained tremendous popularity among men in their thirties and forties. In the meeting to finalize the ad concept, I looked you-know-who straight in the eyes and stated my opinion. I felt myself unintentionally emphasizing the word “transformation” as I spoke. But, there was no disturbance in his face. As always, he looked confident and relaxed.

“What the? A transformation of a car? From sedan to SUV? Are you kidding?” Someone took the fizz out of my soda.

“I saw it because my son wanted to see it so much, but it was really off the wall. The robot transforms into a car, and to an airplane.”

“We could be penalized for excessive advertising.”

“I thought it was a fun movie. It reminded me of the transformer robots that I was crazy about when I was a kid.”

“The computer graphics were something to look at, but they could’ve put more work into the setting.”

“What do you expect? It was based on a comic book, for god’s sake.”

“Really? Well, no wonder. There was a bunch of grad school kids sitting right in front of us in the movie theater. God, they were making so much noise I wondered how little their parents must’ve taught them how to behave in public.”

Untimely disputes about the movie chucked my idea into the garbage.

Finally, you-know-who opened his mouth. “If passion was the only attribute taken into account, that ‘transformer’ idea would surely give us victory, but too bad.”

People here and there burst into laughter.

“Imagine yourselves in a medieval city. Rothenburg in Germany or Orvieto in Italy, for example. You see a Gothic-style cathedral standing like a gigantic candlestick in the middle of a city. A big wedding is being held. Mr. Ch’oe, come down from the platform, it’s not your wedding.” People giggled.

“The bride and groom, blond and beautiful, are in the attire of the noblemen of the medieval era. They come out from the cathedral as the ceremony ends. In the square outside the cathedral, a new SUV is waiting. Metal cans and balloons hanging, tied to the rear bumper. Red carpet leads up to the car, flanked by knights on horses bearing pennants. Now, the newlyweds get into the car. The driver dressed like a horseman starts the car. The couple starts kissing in the backseat. After they kiss, they quickly take off their clothes, not caring who started first. Before we know it, they are dressed in equestrian clothing. The car speeds up, and the medieval city fades in the back and the copy appears. The choice of the chosen ones is always the same! The choice of the top 1 percent in Korea, whether you are in the city or in the country!” After a moment of silence, claps and compliments burst out from the crowd. “You are a genius. We don’t need to see the presentation to find out.”

Even though my concept went straight into the garbage can instead of seeing the light, it went like this. Even though I might not be as eloquent as you-know-who, listen up. Imagine a car that’s powerfully climbing up the mountain, covered in mud. The driver is enjoying the view of a landscape that Mother Nature had created, but suddenly gets startled when he looks at his watch. The car moves at the maximum speed. It goes over the hills and crosses the rivers. Rain pours down. One hand on the steering wheel, and blowing up a balloon and drinking coffee with the other hand. The car then glides to the front of the cathedral. Cans and balloons are tied to the bumper. When the newlywed gets in the car, the car starts off smoothly. The copy that follows is, “The car that gives you more, whenever and wherever.” You don’t have to clap if you don’t want to. What I need is not an insincere sympathy but the courage that makes me face the truth. Don’t worry. Although I’m not myself lately, I still had enough composure to keep this to myself: “You stole my idea this time too. What yours comes down to is the same damn transformation motif.”

“It’s a type of royal marketing. Wouldn’t it cultivate anticapitalistic sentiment? Our society is still not always generous toward rich people,” I carefully jumped in. A chilly atmosphere gathered around me. If I were standing alone in the middle of Jungfrau, maybe this was how I would’ve felt.

“Good point.” There was no loss of composure in you-know-who’s voice. “We’re going to push for radical thinking. The slogan will represent the 1 percent and target the 99 percent. The 99 percent that hates the 1 percent but are actually crazy about becoming that 1 percent. We’re going to tamper with the neurons of antimonial desire. The next is . . .” He paused for a second, spread his arms wide, and said, “Bam!”

* * *

Misŏn and I went out for dinner at a place on the Han River—it had been a while. Now that the decision had been made on the car ad concept, I had the chance to take a break. The car ad will be made according to you-know-who’s idea, of course. If we followed his directions, the shooting would work out just fine. The copy was made. His eloquent presentation will be a sure bet to win over the client’s mind. What distinguished him from others was the fact that he knew more clearly about the mind of the client than that of the customers. Another crown of victory will be added to his already fabulous career.

“Why are you so down?” Misŏn asked in between slices of her salmon steak.

“Do I look down?” Enervated, I replied. Over the window, I saw brown-sugar-like dusk was coming down all gooey from the sky above the Han.

“What’s the matter?”

“Nothing . . .” I hesitated. Maybe I can tell her about my suspicion. She’ll listen.

“Are you hiding something from me?” She was sharp. “Go ahead and tell me. Keeping it to yourself will only make you more stressed out.”

I looked at her, urging myself to speak out. I could tell from her eyes that she was sincere, and I squeezed out the courage, getting a grip on my swaying mind.

“Before you listen up, promise me one thing.”

“What is it?”

The reason for asking someone to promise something is not because you don’t trust them, but because you have fear inside.

“Whatever I tell you, please don’t laugh at me.”

She nodded with assurance. I confessed everything about the real thing that underlay the deep-rooted suspicion about you-know-who. I told her everything about the basis of the doubt that he might be someone I knew before. After I was done, she went into deep thought and didn’t say a word for a long time. I thought I would gain relief if I told someone, but I didn’t. The feeling of swallowing rotten food against my will took over me. I couldn’t fully explain the real identity of the feeling to myself.

On top of the bridge across the river, the decorative light burst out its bulbs, one by one. Under the bridge, where fishing-lamp-like lights illuminated the area, the darkness that rode on the river flipped its body quietly and flowed to some unknown place. I felt like the darkness that united with the river was flowing to the bottom of my heart.

“So you’re telling me our director—Steve Kim, I mean—is the Count of Monte Cristo. Erasing the past and transforming to a totally different person. Then how do you explain the face you couldn’t recognize?” The way she focused on my mouth, I knew I’d caught her interest.

“Plastic surgery,” I blurted.

“Oh yeah, you know a male celebrity who came out with a totally changed face? People were amazed. It looked so natural,” cringing as she said it.

By now, the Han was blended with the darkness. I couldn’t distinguish whether the thing flowing in the dark was darkness or the river. On top of the bridge across the river, the decorative light burst out its bulbs, one by one. Under the bridge, where fishing-lamp-like lights illuminated the area, the darkness that rode on the river flipped its body quietly and flowed to some unknown place. I felt like the darkness that united with the river was flowing to the bottom of my heart.

“But there is one thing I can’t believe. It’s been quite a while since it happened, and you’re not even that close to him. How can you be so sure what you remember is accurate?”

I didn’t expect to be questioned on that. Inaccurate memory . . . Would she believe me if there was nothing worth remembering back then? The time in that town into which I poured all of my high school days, the period that was only geared toward getting the scholarship, was the never-ending slough of my life. Within the pitch-black slough, there is a moment where even the darkness feels like lightning. I gazed at the river hiding behind the darkness and carefully opened my mouth.

“You don’t have to believe me, but I’m sure what I remember is true.”

“It’s not that I don’t believe you, but you need better evidence.” She flushed as she defended herself. At that moment, I thought of the anchor, the word that suddenly came out of my mouth.

“Anchor?” Her eyes became round.

“Yeah, the anchor,” which would be tattooed on the private part of his body.

That summer night, three of us drank on the beach, and it being my first time to drink, I ended up losing consciousness at some point. Where I opened my eyes was a shabby room at an inn. My head pounded to the point of shattering. Next to me was the girl from Seoul sleeping, naked. I couldn’t see T’aeman. I didn’t need to pinch my own cheeks to realize it was actually happening. The smell of mildew ticking the bridge of my nose did it for me. Although I froze up for being so embarrassed, my eyes slid toward the girl. What caught my eyes was the anchor, which was tattooed around where her pubic hair started. It looked like it was hanging deep under the black water plant to tie down the belly button. That image didn’t leave my head for quite some time. Every time I saw T’aeman in school by chance, the anchor that was sunken down in the abyss popped right up. The anchor that was sure to be tattooed on his inner skin as well. In the test I took after that summer break, my rank went down to number two. His name was written above my name in the list. That was the first and last time I lost first place in that school.

When I said, “Only if I get a chance to see his naked body, the truth will be revealed,” Misŏn’s face became petrified as if she chewed on rock. “I’ll do whatever I can to look at his naked body . . .” I pleaded when I looked at her.

“Are you insane? Must you do that to get your suspicion off your chest? I don’t know about this. You know, these days, I wonder if you are the same person I used to like. How could this happen to you?” Her voice trembled.

“If what I remember is accurate, if my inferences match, I’m sure I can find the tattoo.” I also shouldn’t have confessed this to her. I bit my lips out of belated regret.

“Why don’t you give your excellent memory a break? Do you know what day it is? Whenever you run into me at work, you’re cold as a rock, and if we’re within sight of the office, you shake off my hand because you’re afraid people will see us. . . . Are you that afraid of dating me? Do I embarrass you? Is it because I didn’t go to a good school and my parents aren’t rich? Then what made you choose me? Why do you go out with me?” At last, she burst into tears. I realized that it was her birthday only after I saw her running out of the restaurant. One more thing I realized: she looked like the girl from Seoul I went to the beach with that summer.

* * *

Days of struggle passed, and in those struggles I felt threatening eyes. Misŏn ignored me, even when we ran into each other at work, and didn’t reply to any of my messages. Sauna Pak requested early retirement. At his sudden move, everyone was thrown off, but he confessed he’d been thinking about it for quite some time. He said he wanted to end his life as a “wild goose father” and live with his family in the U.S. Some people talked behind his back, saying he made a preemptive move before getting laid off.

At the farewell night out, when Pak went to the restroom, people brought up the buzz about the next person in line.

“You guys are fucked up,” I shouted. “We’re at a farewell party, for god’s sake.”

Everyone looked at me. They looked at me as if they were witnessing an alien in action.

We went barhopping all night. When we came from karaoke at dawn, only five of us were left. You-know-who was also there. Sauna Pak looked at his watch and suggested we go to the sauna together. He said it would be impossible to go home and come back to work on time, and this would be a nice way of celebrating the last moments. He even said he has to go to the U.S. Embassy in the morning. Some people said they wanted to slip out, but Sauna Pak insisted ever so strongly. I quickly became sober. It was such an unexpected chance. My heart pounded and my palms got sweaty. I searched in my pocket and took out a chocolate bar.

“Ch’oe, are you hungry?” you-know-who asked.

“He is the chocolate monster,” Pak answered loudly.

“Almond chocolate, that’s so old-fashioned. Try this. The taste of chocolate depends on the cacao. British noblemen liked chocolate with 99 percent cacao.” You-know-who searched his pocket and found a chocolate bar. The wrapper displayed the cacao content in big letters. 99 percent. I peeled the wrapper, broke off a piece, and put it in my mouth.

“How does ‘Kingdom of the British’ taste?” Pak asked. As the chocolate melted, the bitterness became stronger. On one hand, it tasted like pencil lead and on the other hand, it felt like I had swallowed brandy. When I frowned, everyone chuckled.

“But it leaves you with a sweet taste,” Steve said with a knowing expression.

In the sauna, I kept sneaking looks at the bath towel that covered Steve’s bottom. Alas, it was so snug and concealing I couldn’t see his navel. I got up and left. I dipped myself in the cold tub to cool down and then settled into the hot tub, where I could see the door to the sauna dead ahead. I waited attentively for you-know-who to open that door. My eyes kept closing, like they did that summer day at the beach when the sun was like fireworks bursting above my head. I kept rubbing my eyes to fight off my drowsiness, Finally, out came you-know-who and off came the bath towel wrapped tightly about his waist. The hot tub was steaming and my eyes were fogged. I blinked. That’s better. Above a cloud of steam the black of his pubic area came into view. I swallowed heavily. 99 percent cacao chocolate spread bitterness through my mouth. My tongue searched every recess, but I’ll be damned if I could find that sweet aftertaste he’d mentioned.

Seoul

Translation from the Korean

By Jane Lee & Bruce Fulton

Editorial Note: Read an interview with Kyung Uk Kim in the January 2013 issue of WLT online or in the print or digital edition of the magazine.