The Story of Shit

Author’s note: I wrote this story because I yearn for the days that the wind has swept away. In the neighborhood of fishermen where I was born, we kids didn’t have a bathroom. Only adults had a place where they could hide away to take care of their necessities. Animals and little ones formed one single community out in the open.

Author’s note: I wrote this story because I yearn for the days that the wind has swept away. In the neighborhood of fishermen where I was born, we kids didn’t have a bathroom. Only adults had a place where they could hide away to take care of their necessities. Animals and little ones formed one single community out in the open.

In some part of my memory, everything lives on. No one, nothing has died. Photographs capture snapshots, and every so often, I return to them to remember the stones, the corncobs. The rain would come on suddenly and wash away all that was dirty and covered with flies.

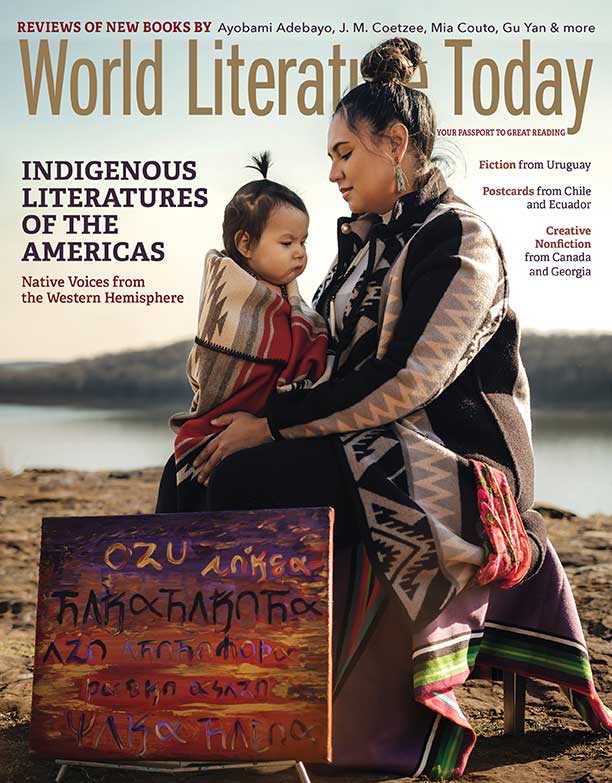

Behind the house, or deche yoo as we say in Zapotec, we kids and animals gathered. Such intimacy. It could be said that my generation knew each other down to the droppings.

This story is dedicated to my brother Manuel (Tarú), my cousin Anabel, my twin aunts Carmen and Socorro, and to all the children who went to the bathroom in the narrow alleyways that formed behind our houses.

* * *

In the mornings I help my neighbor Cista shuck the corn. We sit around a basket of cobs while her husband tells us stories. To express thanks for the harvest, the women of the house make atole with epazote leaves and salsa de chile. They serve it up in gourds to all the neighbors along with tender corn on the cob. That’s how we give thanks for the rain that comes down from the clouds above the cornfields.

When all the kernels have been shucked, I take a few bare corn cobs home with me. On the way, I pick up some rocks that the sun has already pierced with its rays. A little bit warm. I choose the smoothest ones.

When I go to take care of my necessities, a line of pigs follows me to the back of my house. I smile at the children sitting in a row and pull down my pants. When I’m barely seated, the pigs begin to push me with their snuffling fireplug snouts. I watch them from the corner of my eye, like a chicken watches a scorpion she’s about to catch, and I scoot forward so as not to dirty my behind.

Sometimes my cousins were already taking up the whole back of the house. Since I didn’t have anywhere to sit, I went to look for my cousin Anabel, and the two of us went on to Aunt Inés’s house. But her house was almost always full of kids with protruding bellies. If we didn’t find a spot, we went on to Conce Porra’s. We’d usually end up in the alleyway behind Mingu Man’s house.

When we ran into my older brother, he gave us the cepu sign. It’s a key sign you make with your hands. You latch your two index fingers together tight and then let them fall so that someone will stop pooping. To stop this spell from coming true, we pushed and pushed like crazy.

They say that shit passes through a tunnel of tortillas and comes out in different sizes, shapes, and colors, like a rainbow in the sky.

One day when I was playing far from home, I felt a stab in my belly. I started to run, but there was no time to get to one of my usual spots. I managed to reach the house of a boy who I really liked. Just in time I pulled down my pants and squatted. What a relief! There I was when the boy showed up and sat down with me. He smiled but clenched his teeth.

“When we’re done, wanna play?” he asked.

“Yes!” I answered. Then I started glancing around for a rock to wipe myself, but there were none to be found. I was embarrassed to get up and look. He looked at me and then began to scoot over toward me, like guie’ tiqui, the dancing flower that, when it falls to the ground, walks along on tiptoe. He stretched out his hand to give me his corncobs. I finished wiping and said:

“I’ll see you under the fig tree at Aunt Cándida’s so we can play.”

I waited for what seemed like forever, but he never showed up.

Night fell. Mama called us into her arms and began to read us the sky. Venus came out first and then the Scorpion constellation. We saw a shooting star, and my eyelids began to waver. Wondering how that boy had managed to wipe himself, I fell fast asleep.

Caca and its connection to Zapotec, the Cloud tongue

Rixuuna’ lá: to shit your name (Be the shit; Own your own shit)

Guluu íque ti la’pa’guí: to stick your head through a wreath of waste (Get your shit together)

Guidigui’: Shit skin (Not worth a shit)

Gue’ gui’: Drink poop

Gue’ ti carreta ró’ gui´’: Drink a whole load of crap

Gudó guí’: Eat shit

Yexupigui’ deche yoo: Go lick shit behind your house

Lidxi guí’: Shit house (The shitter)

Nuchabe gui’: To be covered in shit

Bizale ti golpe guí: Burp up a gulp of shit (Rancid breath)

Ma gudó guí’ iquebe: Your head already ate shit (You’re full of shit)

Güe’ tata gui’: Drinking too much shit (Bullshit; Talking shit)

Guxuhupi gui’: Shitlicker

Güe’ ti sxumilaga gui’: Grab a big basket of shit

Güe’gui’ oriadu: Eat dried poop (Author’s comment: “You’re not even lucky enough to eat dried poop, much less fresh. . . . I think it comes from the idea that, like the Chinese, we dry our food so that it will last longer. Things like fish, shrimp with salt, meat, and so on.”)

Güe’ diti gui’: Keep eating shit

Lu ri gui’ gunaze’ nisaguie: Rain-swollen shitface (Pizza face)

Eating shit in isthmus towns

San Blas Atempa: Güe’ ti guixihiapa ró’ gui’: Drink a feedbag of shit

Xadani: yesú gui’ guidubi nacalu’: You can go completely to shit

Espinal: Güe’ ti pi gui’: Drink a drop of shit

Translation from the Spanish

Translator’s Note

by Clare Sullivan

I should not be surprised. Natalia Toledo tends to choose topics that make us squirm. She delights in the details of everyday life, down to the dregs and, well, the shit. Since we’ve worked together for quite a while, I would say she enjoys making her reader uncomfortable. But that is not all that she’s doing here when she narrates her relationship with human (and animal) waste. She decided to write all this down in the first place because she was struck by how many Zapotec expressions mention caca. She wanted to record and remember these expressions. And she also wanted to play with language, imagery, and her reader. But when she writes down a story, a poem, or a refrain, something else happens. She is an expert at noticing details and sounds and smells. And these stories, poems, and sayings connect her readers to themselves and to each other. I am grateful that she has bothered to remember and play with these images and especially for her patience with my preguntas de mierda.

Editorial note: See Clare Sullivan’s translations of two poems by Toledo in the January 2011 issue, her essay “The State of Zapotec Poetry: Can Poetry Save an Endangered Culture?”, plus Daniel Simon’s editor’s pick of Toledo’s The Black Flower and Other Zapotec Poems (March 2016).