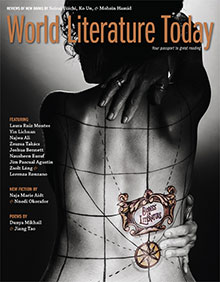

Phantoms as Ambassadors of Sense: A Conversation with Lorenza Ronzano

Lorenza Ronzano lives in Alessandria, Italy, where she works as an existential therapist for the psychiatric ward of a hospital. Zolfo (Sulfur), her first novel, was nominated in the Opera Prima category of Italy’s 2014 Premio Campiello. To accompany “Trespassing,” an excerpt from Zolfo that appears in the September 2015 print edition of WLT, translator Anne Greeott sat down with the novelist to discuss autofiction, the river of writing, and literary lightness.

Anne Greeott: How would you describe the genre of autofiction? What kind of connection does it involve between writing and life?

Lorenza Ronzano: Many authors make an effort to have an almost surgical incision between life and writing: they continue to write stories that are completely abnormal and disconnected from their life, experiences, authority, even from their fears and desires—and it begs the question, then why do they write them?—and on the other hand they carry out their lives filled with work, family, free time, etc. They’re like do-it-yourselfers, they treat literature as a hobby, and they dismiss it as a mere instrument to furnish their personal ambitions with a little extra touch of aesthetics. For example, the academic who publishes a noir novel increases the charm of his very-respectable-but-perhaps-somewhat-sterile position. To honor oneself with the title of writer carries with it a career that might seem too categorical, too meager, too singularly devoted to principles of socially operative pragmatism; to be an attorney and a writer, a teacher and a novelist, a doctor and a poet, etc., is often the ideal power marriage in its most sinister manifestation. Literature as role-play may even at times reach a very refined level, but ultimately it’s no more than role-play with all the stories, the scenes, and the emotions each playing a role.

The writer is a circus dog that must start performing its act as soon as it comes onstage: it may not occupy the stage just to go sniffing around, wagging its tail, barking; it can’t just be allowed on stage simply to be a dog. For literature as performance, that would be scandalous.

This concept of literature as performance doesn’t require the writer to be a well-rounded person but only requires material that will entertain the reader by virtue of its high density—its narrative, conceptional, rhetorical, technical-expressive, or philosophical density. The writer is a circus dog that must start performing its act as soon as it comes onstage: it may not occupy the stage just to go sniffing around, wagging its tail, barking; it can’t just be allowed on stage simply to be a dog. For literature as performance, that would be scandalous.

There are actually some writers who come onstage and take the floor, and for the whole time they don’t even do a single circus act; for the whole time these writers keep their calm and have the courage to be nothing other than people. For example, Kafka writes very freely in his letters and diaries, and in them he reaches unattainable summits of expression, much more so than in his novels, in which he evidently felt required to amount to something. Or else take Anna Maria Ortese in her novel Il Porto di Toledo, where she goes right ahead with an “atrocious style” because it’s clear that’s the only way to give voice to who she is: a fantastic woman-girl-elf-animal hybrid. These writers are true to reality. Antonio Moresco does this as well: he is true to the reality of himself, to the life that befalls him. The life and the years of a man are almost always lengthy, slow, and monotonous. His novel Gli esordi holds intact the courage of a life like that. In this type of literature—literature as a display, as a phenomenon of natural flourishing—the writer expands, spreads out, grows, shows himself for what he is—or for what he is not, or in contrast with what is, by virtue of effort, of struggle, or of the incongruity of his vital impulses mixed into the nexus of billions of other impulses.

AG: What role do images and dreams play in your work? How do you bring your writing to a point where it shows rather than tells the story?

LR: The other day, a man at the library told me, “When something strikes you, that’s where the truth is.” A simple sentence, almost an obvious truth, but I was instantly convinced. Despite its apparent triviality, it seemed immediately true because, in effect, it struck me deeply. I thought that man was right, even though I didn’t expect someone with a background in science—he was an engineer—to express that kind of idea with so much conviction. But when I thought it over, it occurred to me that actually there really was no contradiction between his “creed” and his background because a true scientist has to be unbiased. A truly objective approach requires a lack of prejudice; the true scientific method, I thought, is to learn to trust what one feels.

So that man had just synthesized in a single sentence my way of moving ahead, not just in writing, but more generally the way my interior life works, all of my perceptual life, which might be what counts most in writing, even more than sitting down and hitting the keys on the PC.

When I write I do nothing more than translate the things that have struck me into words. I might say that I entrust myself to the world and to what the world shows me from one turn to the next. I trust in its apparitions, its manifestations, its epiphanies.

You can understand then why my style emphasizes concrete images, dreams, and anecdotes: because when I write I do nothing more than translate the things that have struck me into words. I might say that I entrust myself to the world and to what the world shows me from one turn to the next. I trust in its apparitions, its manifestations, its epiphanies. I perceive more expressive power in these than in any storyline planned out on a table.

It’s not that a writer shouldn’t use reason, not that planning should be completely cut out, but that all that comes into play in a second phase, after the first layer of cream has been skimmed from the imagination, that the world makes an impression on the plate of our own sensitivity in the same way that light does on the film in photography. Writing, then, becomes a record of phenomena, and I mean phenomena as understood in the etymological meaning, from the Greek phainomenon, “that which appears,” and also, very eloquently, “whatsoever effect, as observed in bodies,” which has the same root and meaning as fantasma: that which presents itself continually to the mind by means of an image and discloses a meaning in its wake. Writing as a collection of phantoms, or of phantoms as ambassadors of sense, of an idea.

Of course, these practices derive from my personal ideal of literature, which I intend as the creation of a second world within this first world, as a reaching for a second nature over there, or over here, beyond this primarily human, earthly nature that all of us are called on to live every day.

AG: In a different interview you mentioned your method of writing and said, “I don’t love the river [meaning the river of narrative]; I sift through it.” How would you describe your writing process—do you write every day? Do you already have an idea of the structure of the novel when you begin? What kinds of revisions do you do? How do you “sift through” the river?

I don’t write every day, but I think every day. Of course not in a preplanned way . . . you could say that every day I’m careful not to let whatever could nourish my voice slip away. I really try to recognize whatever is mine, dispossessed, wandering out in the world, so that I can reclaim it.

LR: I don’t write every day, but I think every day. Of course not in a preplanned way . . . you could say that every day I’m careful not to let whatever could nourish my voice slip away. I really try to recognize whatever is mine, dispossessed, wandering out in the world, so that I can reclaim it. In this sense I “sift through the river,” with this predatory way of writing of mine. When I feel that yearning, I can catch sight of a mouth, a pair of eyes, and a look even on the face of a ficus plant or an ashtray. I feel like shaking up the objective nature of things just to be able to see myself reflected and recognized in them. Maybe I reduce things to being human. I sift through the river in the sense that, to me, writing is a way of carefully considering the world, of putting it through a filter: on one side the world enters—nudo e crudo—in all its absurdity and indifference, and on the other side what comes out is whatever manages to pass through the filter of human meaning. In this sense writing is like a big stomach that tries to gulp down as much world as it can in order to digest it and absorb it. Literature is the world vaccinated, assimilated. We’re immersed in the foreign, the unknown, the unfathomable: every day, everyone in their own way does something to make this unfathomability a little more familiar and known. Literature does this, too. It’s an absurd attempt in the end. You do all this work to “reclaim the unknown,” but in the meantime the river continues to flow and to overflow into other unknown and unreachable territories. It can be noble work, but it’s hard and in vain, like the efforts of Sisyphus. But we keep on doing it.

AG: The narrator in Sulfur has to face her version of evil, her particular suffering—but the style and the writing (in my opinon) don’t become weighed down by this content; actually, the style seems to subtract weight, as Calvino writes in his essay on lightness, from the material within it. How do the elements of lightness and weight interact with each other in Sulfur?

LR: In ancient kung fu if you feel afraid of being hit, you will be hit; if you feel afraid of hitting, you will be hit. Fear generally leaves no escape, because it involves thinking at the wrong moment. Fear is thinking rather than acting, reasoning off-tempo. Fear takes the life out of action, gets in the way of movement, and weighs down the body. In writing, the same thing happens: when you write the first draft, you have to stop thinking or using logic or it becomes rhetorical, heavy. Just as fear and rhetoric immobilize and weigh down the body, reason embalms writing, makes it heavy, too literary. Training always has to come first so that you’re not afraid when the adversary shows up. Training so that you expect the adversary in every object, you consider each thing as if it were the adversary. You sense the world as the adversary. It’s like that with writing: you have to have already thought first about what and how to write during your life, not while you’re writing.

It’s one of those knots that I’ve worked hardest to untie, this attempt to lighten the element of weight. Lightness is a question of the presence of spirit. If you write about a thing, you have to be all there, not just your head or your knowledge. Just think of the gigantic, crushing accumulation of academic-literary culture hanging over us: if you don’t put everything into it, it crushes you, and you turn into a mummy. There aren’t any topics that are more heavy or less heavy; the weight, the gravity comes from stereotyped thoughts. You can write in a light way about everything, but if you’re not careful, when you take the pen in hand, there’s always a risk that the common places, common rhetoric, and stylistic imperatives will do the thinking for you, that you are actually being thought by them! And so you always have to be careful to have your whole self present while you write in order for it to be light.

February 2015