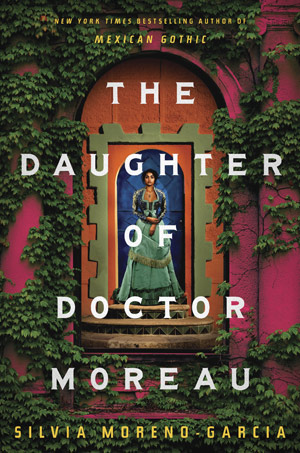

The Daughter of Doctor Moreau by Silvia Moreno-Garcia

New York. Del Rey. 2022. 320 pages.

New York. Del Rey. 2022. 320 pages.

SILVIA MORENO-GARCIA is known for an intersectional feminist approach to genre fiction that resists intertwining currents of sexism, white supremacy, and colonial and neocolonial power. With the 2020 publication of Mexican Gothic, her sixth novel but the first to appear on the New York Times best-seller list, the work that Moreno-Garcia had long been doing finally became a matter of public knowledge. Two years later came The Daughter of Doctor Moreau, an aesthetically rich and politically significant retelling of H. G. Wells’s 1896 novel that would transplant Wells’s original premise to the late nineteenth-century Yucatán. Rendered in gorgeous prose that maintains its allegiances to the often-maligned world of commercial fiction, Moreno-Garcia’s narrative features a young woman protagonist named Carlota, the eponymous daughter determined to defend herself and her world from encroaching danger.

Described by its author as “loosely inspired” by Wells’s Doctor Moreau, the retelling makes pointed interventions that disrupt the legacy of its canonical counterpart. The novel’s alternating close-third points of view are two alternatives to the first-person narration of Wells’s earlier text, which privileges an outsider’s expressions of revulsion at what it terms “grotesque” in the identities of Moreau’s “Beast People.” In Moreno-Garcia’s reinvention, the real grotesqueries are expressions of white Eurocentric power: most obviously the French-born Moreau’s horrific experimentation on animals and in some cases on women of color, but also the callous responses of “European-descended” Mexican characters to the plight of Moreau’s victims, their viciously racist attitudes toward the novel’s Indigenous Maya community against the backdrop of the Caste War of Yucatán, and even the pale gothic visuality of whiteness, which the narrative imbues with its own visceral horror. Giving voice to Carlota’s perspective in particular allows Moreno-Garcia to reject the imperative that subaltern figures like Wells’s puma-woman can only be gazed on distantly in their suffering and their revenge.

Moreno-Garcia has been candid in speaking out about the specter of white supremacy in her life and the lives of her loved ones. In 2019, then the author of novels including Signal to Noise and The Beautiful Ones, she took aim at the pattern of discrimination against writers of color within the Canadian publishing industry: “There was nobody here who wanted to represent me,” she commented. Moreno-Garcia’s experience of being “treated worse than white writers—ignored or not given the resources to succeed” represents an extension of the same persistently pathological system that The Daughter of Doctor Moreau invokes and resists. Likewise, the novel is insistent in refusing the racist logic that led others to tell Moreno-Garcia’s mother that she “was ugly due to her dark skin and Indigenous heritage.” The claims of “upper-crust Mexicans” to “a pure, white ascendancy” are pointedly problematized, with special attention to the stigmatization of non-white-presenting womanhood within a social apparatus that fetishizes the “girls of milk and honey” who are Carlota’s opposites.

Just as it plays with and against Wells’s vision, however, Moreno-Garcia’s novel adopts an ingenious speculative approach that will not be confined by the bleakness it reflects. By the close of The Daughter of Doctor Moreau, the eponymous heroine has come into her own, claiming forms of agency that, as the book itself underlines, are virtually unheard of for “dreadfully young” unmarried women in Carlota’s fin de siècle universe. As Doctor Moreau’s daughter uses these resources to enact change on a larger scale, we begin to see that the most exhilarating strength of Moreno-Garcia’s method is its fierce embrace of possibility.

The Daughter of Doctor Moreau is important because of what it refuses to look away from—but also because of the joy, the beauty, and the victories it allows us to experience and imagine.

Suzanne Manizza Roszak

University of Groningen