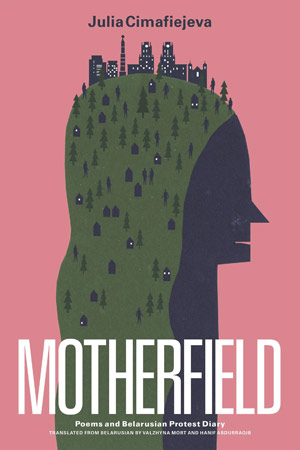

Motherfield by Julia Cimafiejeva

Dallas. Phoneme Media. 2022. 128 pages.

Dallas. Phoneme Media. 2022. 128 pages.

OUR SOCIOPOLITICAL WORLD is hemorrhaging; when an adroit poetic spirit on the front line documents it with such candor, rigor, and talent, we are best served by paying attention.

Belarusian poet Julia Cimafiejeva’s first collection in English, Motherfield, begins with a “protest diary”—a prose section written originally in English documenting the lead-up to, and the especially shocking aftermath of, the 2020 presidential election in Belarus, day by day. The grounded tone and assiduous, cumulative detail of these selected diary entries inform their expressive power. Reading them, we can apprehend a “normal” sensibility and society thrust into rupture and extreme abuse. Besides a reader’s sheer gratitude for this unflinching chronicle of state psychosis played out on a daily, personal level, one haunting implication communicated by its tone of familiarity is that such a rupture could really happen anywhere—even “here.” Beyond its documentary value, this is perhaps its main service. Here’s an excerpt from March 11, 2021:

Raman was murdered because we came outside to ask the masked strangers why they were cutting off white-and-red ribbons that decorated the fence. Because of the ribbons he was tortured in the car on the way to the police station, then his maimed body was thrown on the porch, and the police officer called the ambulance to take him to the hospital where he got into coma and died. // We were aghast. Anyone could have been in Raman’s place. Anyone who would defend the neighbourhood where he or she lives.

The middle section of this volume is a selection of poems presented bilingually, side by side in Belarusian and English translation. Here, disenfranchisement is given poetic voice, where, in stark and useful contrast to the diary, it is a visceral tone of horror at what the poet has been experiencing that predominates—and is sustained. This facility seems baked into the poet’s DNA—as, we are told, she “was born in an area of rural Belarus that became a Chernobyl zone when she was a child.”

Many of these poems flow quickly in relatively short, irregular lines down the page, suitable for transmitting emotional essences. Here we have core reactions and reflections—to the state, relationships, the prevailing social order, and the complex nature of family ties, as in the poem “Umbilical”:

. . . frightened, you hid / in the swamp of ice / under the weight of wet braids // my name is a mirror / of your name / green seeds of my eyes / grew out of yours // but I / sold / your inheritance / for a dry // crumb of freedom / I cut // long and thick / umbilical hair // I thought I unburdened / myself // but even invisible / the braid grows / with memory // we spent three years together / and then headed out / into two opposite directions / you under the earth / and me onto the earth // Two cold coins on your eyelids / the green lace of pine paws . . .

A ceaseless inventiveness carries this selection of poems inexorably forward, as in the startling poem “MSCRRDG”: “. . . was supposed / to be what / tadpo- / poppy / something m- / uuuuuuuugh / than // hmm . . . embryoo / bry / breathe / still young / you will have / more // what?”

The poet eventually chooses exile in Vienna, and so the poems also reference the complex of guilt and necessity engendered by this choice. In a final part, in original English, “My European Poem” gives a largely more prosaic account, sometimes anthemic and lined poetically, of the complicated yet secure place the poet has arrived to:

. . . When I tell it in English, / I want to pretend that I am you, / That I don’t have that painful experience / Of constant protesting and constant falling, / That nasty feeling of frustration and dismay. / I want to pretend that I have a hope, / Because when I tell it in Belarusian / I realize, we all realize, there is none.

To be translated into English by another powerful expatriate Belarusian poet, Valzhyna Mort, together with accomplished American poet Hanif Abdurraqib, gives this book its uniquely pitched voice in English, at once recognizable yet crossing irreversibly a raw societal edge many of us may never know.

This book is a sword; its poems cut through so much clutter to the white-hot wire of social, political, and personal injustice—warranted, searingly expressed, and yet somehow also nondogmatic, intuitively right, and artistically original. These poems speak volumes; to an astute reader, they can also serve as a warning. It is a voice that deserves and rewards our attention—hopefully you can give it yours.

Andrew Singer

Trafika Europe