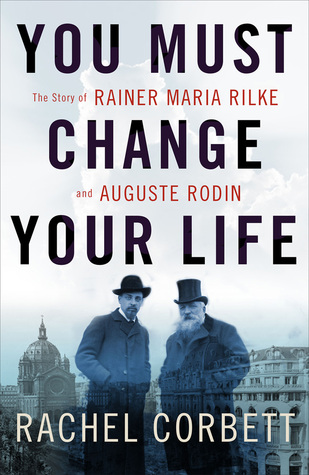

An Encounter for Self-Help and Art Mastery: A Review of You Must Change Your Life: The Story of Rainer Maria Rilke and Auguste Rodin, by Rachel Corbett

Anecdotes often shed light on the way we see art and literature. A few weeks ago, I was skimming through Rachel Corbett’s book in the Paris metro when a young man came toward me and asked me whether the title, You Must Change Your Life (W.W. Norton, 2016), referred to some sort of self-help book. I first smiled at his comment and then thought that the title was somewhat deceptive. As the young man was still staring at me, I had to explain that Corbett’s book was actually about the story of renowned French sculptor Auguste Rodin and Prague-born poet Rainer Maria Rilke. The man was still unsatisfied, so I further explained that the title, derived from a famous Rilke poem, hints at the way creation requires the young artist to overcome his fears and reshape his life. In what I took for a sign that creation, effort, and culture are all intertwined notions, my conversation with the stranger ended at the station Bibliothèque François Mitterrand as he stepped off the metro and gave me a last nod of gratitude.

Anecdotes often shed light on the way we see art and literature. A few weeks ago, I was skimming through Rachel Corbett’s book in the Paris metro when a young man came toward me and asked me whether the title, You Must Change Your Life (W.W. Norton, 2016), referred to some sort of self-help book. I first smiled at his comment and then thought that the title was somewhat deceptive. As the young man was still staring at me, I had to explain that Corbett’s book was actually about the story of renowned French sculptor Auguste Rodin and Prague-born poet Rainer Maria Rilke. The man was still unsatisfied, so I further explained that the title, derived from a famous Rilke poem, hints at the way creation requires the young artist to overcome his fears and reshape his life. In what I took for a sign that creation, effort, and culture are all intertwined notions, my conversation with the stranger ended at the station Bibliothèque François Mitterrand as he stepped off the metro and gave me a last nod of gratitude.

Later on, when I finished reading Corbett’s book, I thought again of my hasty reply to the stranger and realized that his guess was probably right. Indeed, the moving story of Rilke and Rodin is worth as much as the best self-help books and manuals, and one could definitely learn a lot from their relationship. If Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet stands as an acclaimed and oft-cited work, his encounter with Rodin is definitely less known.

Throughout their unique and stormy relationship, and despite the difference of their cultures and trajectories, Rilke and Rodin embodied some of the most frequent and torturous questions related to creation and art mastery.

In 1902 Rilke moved to Paris to write a book about the French sculptor, whom he admired as the typical and most accomplished model for artists and creators. Throughout their unique and stormy relationship, and despite the differences between their cultures and trajectories, Rilke and Rodin embodied some of the most frequent and torturous questions related to creation and art mastery. In Corbett’s words from her introduction, You Must Change Your Life is “the story of how the will to create drives young artists to overcome even the most heart-hollowing of landscapes and make their work at any cost.” In nineteen chapters organized into three sections, Corbett reconstructs the story of an original yet improbable encounter that questions interconnected practices of artistic creation, reciprocal influence, and individual self-fulfillment. Beyond the Rilke-Rodin relationship, the trope of encounter structures Corbett’s account and resonates in the conjunctive titles of the three sections: “Poet and Sculptor,” “Master and Disciple,” and “Art and Empathy.”

Part 1 of the book traces the origins of the encounter between the two artists. In alternating chapters, Corbett reconstitutes the trajectories of Rodin and Rilke before August 1902, when the poet left the German village of Westerwede to travel to Paris with the aim of preparing a monograph on the French sculptor. Rodin’s early vocation for sculpture was nurtured by observation and working sessions at the Louvre but challenged by the rejection of his successive applications to the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. Rilke, who was born after his mother lost an infant girl, grew up with a disrupted gender identity. He fled Prague’s contradictory social and linguistic setting to Munich where he met German writer Lou Andreas-Salomé, who would become his muse and artistic mentor. Corbett’s account suggests that Rodin’s and Rilke’s trajectories were shaped by the quest for the meaning of being an artist and the significant impact of encounters, notably Rodin’s love affair with young sculptress Camille Claudel and Rilke’s engagement with Clara Westhoff, a former student of Rodin, whom he married in April 1901.

Rodin and Rilke had to work against dogma, against the establishment, and sometimes even against the course of history.

Part 2 of the book, which is also the longest, opens with Rilke’s excitement upon his arrival in Paris and first visit to Rodin’s workshop in the suburb of Meudon. The encounter provided Rilke with a striking insight into Rodin’s art, with the French sculptor defining his activity as work and labor, and privileging the representation of hands in his creations. Corbett aptly notes that the dynamic bodies of Rodin’s sculptures and his mantra, “Travailler, toujours travailler,” reshaped Rilke’s vision of life, art, and creation. After completing his monograph on Rodin, Rilke started his famous correspondence with young poet Franz Xaver Kappus and made his way to Tuscany and later to Scandinavia. Corbett pinpoints that Rilke’s stay in Paris allowed him to learn how to “see into” material objects and human lives, a fundamental lesson for the writing of his Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge.

In September 1905, nearly three years after his first visit, Rilke would be hired by Rodin as a personal secretary to manage his mail and other business matters. From daily activities and conversations to regular excursions, this proximity would open a new chapter in the relationship between both men. Corbett’s account shows how Rilke witnessed significant moments in Rodin’s career such as the preparation of the bust of English playwright Bernard Shaw and the installment of The Thinker at the Panthéon. However, following an unexpected quarrel over a private letter, Rodin fired Rilke after nine months of service, throwing the poet into a state of anxiety and sorrow. This separation coincided with the increasing alienation of the French sculptor from the new generation of artists. In 1907, when Rilke returned once again to Paris, he came across the works of French painter Paul Cézanne and found in them what Corbett describes as a continuation of Rodin’s vision of artistic creation, based on empathy with and movement of objects. Finally, Corbett describes the reunion of Rilke and Rodin in the Hôtel Biron, which would later become the official museum of the French sculptor.

In part 3 of her book, Corbett starts by referring to Freud’s supposed words about Rilke’s sadness and vision of death following a walk he took with him and Lou Andreas-Salomé in Munich in the summer of 1913. Two years earlier, Rilke had settled in the Duino Castle in Trieste as a guest of Princess Marie von Thurn und Taxis. Corbett recalls that the isolated and bleak environment of the castle would be reflected in Rilke’s Duino Elegies, a collection suffused with melancholy and suffering. On the brink of the First World War, an aging Rodin would publish Cathedrals of France, at once a complaint and a fervent call to save France’s architectural heritage. When the war broke out, Rodin was forced into exile while Rilke found himself enlisted in the military reserve. Corbett’s account draws a parallel between Rodin’s late marriage, followed by the death of his wife, and Rilke’s final stay in Switzerland alongside his last lover, Baladine Klossowska. The poet died in 1926, nine years after his French “Master,” as he used to address the sculptor in their correspondence.

Beyond the story of Rilke and Rodin, Corbett’s book provides a thorough immersion into an era when the act of creation and the status of artist were the subject of much uncertainty and questioning. Rodin and Rilke had to work against dogma, against the establishment, and sometimes even against the course of history. Their unique story, Corbett’s book suggests, hints at the difficulties of sustaining creation and friendship in a world driven by doubt and suffering. The story of Rilke and Rodin is one of admiration, reverence, and, most importantly, empathy.

Corbett uses this last concept, which originates in the philosophy of art, to grasp the legacy of both figures and investigate their understanding of artistic creation. One could argue that this is just one way to approach the multifaceted relationship and the specific trajectories of Rodin and Rilke. More than a century later, however, their encounter remains a symbolic moment of inter- and transartistic dialogue, a unique space of reflection on the power of creation and the agency of artists. If Rodin’s voice, as suggested by Rachel Corbett in her introduction, resonates in Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet, it also invites readers to reflect on the way sculpture could mirror poetry and vice versa. If impressions can be carved in bronze and marble, Rilke’s poetry can certainly offer new perspectives to look at Rodin’s sculptures.

Ultimately, the reader of Rachel Corbett’s book might be tempted to identify with young poet Franz Xaver Kappus or young painter Balthus, the son of Rilke’s last lover, both aspiring creators who received letters and guidance from their master. Corbett’s original book stands as an urgent invitation to revisit both Rilke’s poems and Rodin’s sculptures. Like Kappus and Balthus, the reader of Corbett’s book is invited to find his way to learning from eminent creators and becoming a master in their footsteps. The stranger from the Paris metro was certainly right: the encounter of art and letters is most effective for self-help and art mastery.

Oxford, UK