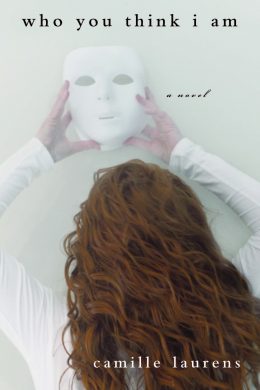

A Losing Battle with Social Identity in Camille Laurens’s Who You Think I Am

Laurens explores the seductive danger of a digital fountain of youth in this novel about women’s identity and agency in midlife.

Technology and gender standards collide in Camille Laurens’s new novel, Who You Think I Am (Other Press, 2017), a harrowing and challenging book that questions the nature of control in an age of digital obsession.

Claire Millecam is nearing fifty and going through something of an identity crisis. She’s a divorced lecturer carrying on a taxing affair with a younger man named Joe, whose cruel manipulations leave her both wanting more from him and trying to gain the upper hand. To do so, she creates a fake online profile for a twentysomething Portuguese woman named Claire Antunes. As this younger woman, she strikes up a friendship with Joe’s friend Chris, who once told the real Claire to “Go die.” But what begins as a means to keep tabs on Joe quickly evolves into a complex real and digital relationship—a pseudo-ménage-à-trois between Claire, Chris, and this digital cypher. Over time, Claire struggles to discern where the real her merges and breaks with the fake her. She slowly unravels as she strives to find a balance between the recklessness she finds in Chris in reality and the kindness she finds in his online presence.

Told through assorted primary sources (a police interview, a psychiatric transcript, and a letter, among others), the story of Claire’s buildup and breakdown is almost entirely relayed through her voice. Professorial and intellectually engaged with the nature of what it means to be a middle-aged woman in a society that favors youth, Claire’s observations are sharp, comparative, and at times biting. But the book’s richness comes in part from the idea that she’s responding or speaking to someone—some man, in all cases—and that the male gaze is in some sense shaping her responses. The fact that she’s reflecting on her own mistakes and her own adoption of a digital identity adds a defensive edge to many of her more pointed remarks; she’s parrying with an unseen adversary and trying to gain the upper hand. But she needs something from them, leaving her on her heels almost all the time.

The alternate profile is at once a means for her to gain some semblance of control and for her to re-create herself in a more desirable way—to use the trappings of youth to win the love she desperately wants.

The juxtaposition of rage and desire is deep for Claire. She both wants to be wanted and resents the steps she feels are necessary to gain attention from men; she sees clearly the malice both Joe and Chris seem to feel for her but can’t get past her need to be seen by them. The alternate profile is at once a means for her to gain some semblance of control and for her to re-create herself in a more desirable way—to use the trappings of youth to win the love she desperately wants.

She returns again and again to the nature of “death” for women, both literal death and the death of desirability. Claire obsesses over Chris having told her to “go die,” in a casual moment of thoughtless cruelty that seems to encapsulate, for her, what it means to be a woman. She says early on, “It’s a tragedy being a woman. Wherever you are. Always. Everywhere. It’s a fight, if you like. But because we lose it’s a tragedy. . . .Women are condemned—by force or by contempt—to die. That’s a fact, everywhere, all the time: men teach women to die.” In this light, her fake profile could be a ghost and, in some ways, is—she uses a picture of a niece who died years earlier, creating an intergenerational confusion that is at once exploitative and haunting.

Laurens, as translated from French into English by Adriana Hunter, excels at creating an at once expansive and hyperfocused narrative. The reader gets the sense they are watching a caged animal, both observing and forcing her to be observed. The line between willingly giving up her story and being forced to is thin, and as Claire vacillates between reveling in the opportunity to explain and feeling cornered, the reader’s role shifts from audience to antagonist. Combined with the plot’s twists and turns, the net effect is a complex interrogation of the place of women in society—and the role of social media in giving us the illusion of control.