Mni Wiconi / Water Is Life: Photographer John Willis Honors the Water Protectors at Standing Rock and Their Struggle for Indigenous Sovereignty

![]()

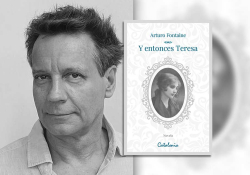

What defines a moment, a movement? The cause or the people who defend it? Too often both are overshadowed by chaos, destruction, and misdirection. John Willis’s Mni Wiconi / Water Is Life (George F. Thompson, 2019) finds a refreshing sense of clarity between the two. Told from the perspective of the members of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, the greater Sioux Nation, tribes from far and wide, and allies, Mni Wiconi seamlessly blends photography, art, and essays into our experience on the Great Plains.

The words and imagery are not my own but tell my story, as a member of the Oglala Sioux Tribe. Though my tribe’s reservation was set a few hundred miles south, we are of one nation, the Great Sioux Nation. These are our stories of the everyday injustices of what it truly means to be a Native in the Dakotas. The events here are one, of many. They are not unique. To be an Indian is to be discriminated against, to be defined as less than. #NoDAPL was a wider call for change; today, the Black Lives Matter movement echoes a similar sentiment. One day, we will break the cycle of separation.

A common theme throughout Mni Wiconi is the peaceful and prayerful protest of the Sioux.

The construction of Energy Transfer Partners’ Dakota Access Pipeline near Bismarck, North Dakota, was contested and subsequently moved for the safety of its citizens. The Water Protectors, known in the media as violent protesters, sought only the same safety. John Willis masterfully shares the Great Sioux Nation’s experience, pain, and mission to be counted as people like any other in America. A common theme throughout is the peaceful and prayerful protest of the Sioux. While that is true, the Sioux were known as warriors. We are warriors, merely in a contemporary form. We fought without violence in protest. However, we fight in courts across the country for not only what is right but our rights, treaty rights written by their own hand.

As an ally, Willis conveys his own experience, gives context and imagery without drowning out our voices. Each essay is written as it was told. Lakota histories and stories are passed down via oral tradition. As children we make fry-bread with our grandmothers, fish with grandfathers, and listen. Our job is to listen. We have a unique way of telling a story. The cadence meanders like a lazy river. A pause might seem to carry too long. Explanations and tangents lend a fuller understanding. The voices of our elders lift off the page.

The opening photos immediately took me back to the early morning at Oceti Sakowin camp. Willis opens with a photo set of the morning mist, a thick fog that feels both refreshingly crisp and eerie. As the dawn rises, Guy Dull Knife’s voice cuts through the mist covering a sleeping camp, “It’s a good morning. Get up!” My grandfather gave hope and protection for the unknown we would face that day with a morning prayer over a loudspeaker. Though he has passed on, he remains within us. His prayer still holds. Readers can experience his prayers and the spirit of camp life via a playlist Willis includes on his website.

Each page forward gives life to what camp was. Over time, it ebbed and flowed but was a true community. Flags of countries, tribes, and groups might signify a section of the camp, but all were welcome. If you were hungry, cold, needed a ride, a medic, or a sympathetic ear, there was always a place for you. Some days, we’d eat from a taco truck that came from Portland or buffalo from down the road because people wanted to feel connected and contribute in any way they could. At night, small fires, songs, and laughter carried through the wind, silenced only by the helicopters that flew overhead at all hours.

Violence was never the means to an end. Intimidation by law enforcement was to be expected but never to the extent that night. November 20, 2016, was a cold, black night. Backwater Bridge had movement on the opposite side of a barricade. Suddenly, tear gas, rubber bullets, bean bag gunfire, and a torrential downpour of water guns rained down. Photos of the escalation bring that night to reality. Clouds of tear gas fell on the unarmed, visible only from spotlight and vehicle lights. It was bloodshed and terror.

Weapons of war were deployed on American soil on American people.

“This clearly is a combat wound,” a combat veteran from the camp’s medic team relayed to Willis as she tended to the injured. Weapons of war were deployed on American soil on American people. Yet they were blamed. Veterans of all generations came to defend the protectors. They stood in front of those they’d sworn to defend, against their own government. It was a cold day. Their jackets and faces were white, frozen from the snowfall. The photos from that day are reminiscent of the Wounded Knee Massacre. It’s bone-chilling.

“Things will never be the same again,” Mark Holman laments in his poem “Two Roads.” While we cannot change our past, what follows are our elders, youth, and friends hope that what happened near Cannonball, North Dakota, along the Missouri River will break the cycle of separation.

Mni Wiconi / Water Is Life relays a message of hope for the future in the face of adversity.

Mni Wiconi / Water Is Life relays a message of hope for the future in the face of adversity in a way traditional media did not. We are all just people. Water is life. We are all made of water. No one can survive long without safe drinking water. Elementary science classes teach us that the water cycle is a closed loop. The rain that falls from the sky and the groundwater below nourish our lands and, in turn, our food. If one part of the cycle is broken, the entire system is contaminated. It is all connected, as we are all connected. Our actions and our inactions matter.

In Lakota culture, whenever we come together, we say a prayer in thanks, for our ancestors, our families, and for everyone to safely make their way out into the world, and it ends with the words: Mitakuye Oyasin (We are all related).

Rapid City, South Dakota