People of the Books

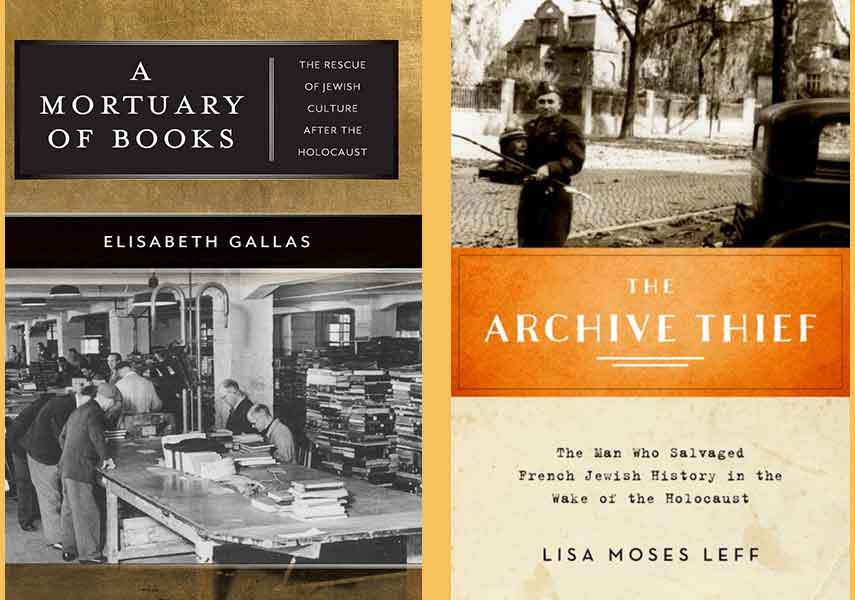

Ever since early Islam, Jews have been dubbed the people of the book. The title stuck in European lands too, a deferential nod to the role of the Hebrew Bible in the Western canon, the breadth of Jewish literacy (never universal, often gender-specific), and the sheer productivity of Jewish authors—or today, Jewish and non-Jewish authors writing about the subject. I prefer this paean to bookishness, bestowed by outsiders, to Ecclesiastes’ musing, “of the making of books there is no end,” which sounds like unwarranted kvetching. Elisabeth Gallas’s A Mortuary of Books: The Rescue of Jewish Culture after the Holocaust (NYU Press, 2019) and Lisa Moses Leff’s The Archive Thief: The Man Who Salvaged French Jewish History in the Wake of the Holocaust (Oxford University Press, 2015) confirm the verdict of Jorge Luis Borges, who called the book the most astonishing human instrument. It seems the desire for preserving books is also lodged deep in the human soul. These two volumes stem from the desire to recount the efforts to rescue books and scrolls and ritual items from the fires of the Holocaust. Both volumes chronicle the life-affirming response to the Nazis’ nihilistic intent to destroy not only Jewish lives but any vestige of Jewish learning.

Gallas and Neff confirm the verdict of Jorge Luis Borges, who called the book the most astonishing human instrument. It seems the desire for preserving books is also lodged deep in the human soul.

Alon Confino’s elegant A World Without Jews (2014) documented the Nazis’ book burnings, which began with the riotous destruction of the works of political opponents in 1933 but culminated in the burning of Bibles—the book of books, as the Bible came to be called in the Enlightenment—on Kristallnacht (November 9–10, 1938). With the invasion of Poland in 1939, special arson squads followed the advance of the German army, and bibliocide became part of the vaster program of genocide. The Nazis gave a twisted meaning to Heinrich Heine’s prediction that “where they burn books they will burn people” and also belied Freud’s initially sardonic reaction to 1933 (“only books?”). Confino’s work shows that the war against books and the war against Jews were intimately linked. The first historian who understood the events of 1939–1945 writ large as The War against the Jews (1975), Lucy Schildkret Dawidowicz, emerges as a major figure in Gallas’s story.

Dawidowicz belonged to the distinguished quartet, along with Salo Baron, Hannah Arendt, and Gershom Scholem, who took action in dark times, to borrow one of Gallas’s chapter titles. The heart of Gallas’s meticulously researched and extremely ambitious book relates the story of the Commission on European Jewish Cultural Restoration (JCR). While the commission went through a few iterations and had a few loci, the epicenter lay in Offenbach, Germany, where the remnants of Jewish culture were first gathered and then eventually sent to new homes. These items were the Displaced Texts, rather than Displaced Persons (DTs instead of DPs), that had avoided destruction, partly by chance, mainly as a result of the Nazi pilfering and creation of private collections driven by pure greed, but partly from the bizarre “academic” centers such as the Institute for the Study and Eradication of Jewish Influence on German Religious Life, as chronicled in Susannah Heschel’s The Aryan Jesus (2008).

The Monuments Men, made famous by the Hollywood movie, gathered much of the material at Offenbach. Gallas’s work offers tribute to American values at their best. Following the scathing Earl Harrison Report, Americans made a concerted effort to do something concrete for the survivors of the camps. One initiative of the JCR was to publish a full edition of the Talmud, arguably the most reviled book of all time, in 1948 by Winter Verlag in Heidelberg. (Yes, that Heidelberg, where Martin Heidegger served as university rector under Hitler.) Formally presented to General Lucius Clay, the volumes were dedicated to the United States Army. “The Jewish DPs,” reads the inscription, “will never forget the generous impulses and the unprecedented humanitarianism of the American forces, to whom they owe so much.”

This incident counts as but one emotional high in the book, eclipsing the unsurprising in-fighting between Zionists and non-Zionists, heads of the German Jewish communities, et al., over who should get what. Gallas intervenes in the scholarship to detail this case of Jewish activism in the immediate aftermath of the Shoah, wherein the activists were thoroughly aware of the high stakes of both commemoration and propagation. Gallas recalls a side of Hannah Arendt as a battler for Jewish lives and culture, often obscured by her Eichmann book and the revelation of her affair with Heidegger (yes, that Heidegger). Salo Baron and Gershom Scholem, so often contrasted in terms of historiographical method and Jewish politics, shared a common goal in the years following the war: recovery. Finally, Lucy Dawidowicz, younger and less established than the others, honed her life’s mission at the JCR, having already acquired special interest in recovering the world of Yiddish culture she got to know at YIVO in Vilna before the war, eloquently recalled in her memoir From That Place and Time (2008).

One of Leff’s many illuminating discussions treats the impact of Szajkowski’s thefts and the role of archives and archivists generally in shaping the history we tell.

Lisa Leff, a distinguished professor at American University, tackles a more ambiguous story: Zosa Szajkowski’s tortuous path from resistance fighter, to US Army Intelligence officer, to YIVO Samler (i.e., collector of Jewish artifacts), to seminal scholar of modern French Jewry, and, ultimately, into the titular archive thief. Almost every turn in Leff’s tale surprises, perhaps none more so than the long gap between Szajkowski’s first apprehension as a document thief in 1961 in Strasbourg and his suicide in 1978, shortly after being arrested outside the New York Public Library. For seventeen years librarians and archivists managed to look the other way while this strange, short, haunted man acted. (How thrilling to imagine that as a high schooler I might have passed Szajkowski with a briefcase of contraband, ascending between the NYPL lions and turning to the left to enter the Judaic Reading Room.)

Events in Poland determined Szajkowski’s baseline: he arrived in New York in 1941 to find a letter from his father in the Warsaw ghetto detailing their imminent starvation. Having lost many members of his family in the Holocaust, Zosa Frydman (his given name) began with the laudable motive not dissimilar to the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee and YIVO workers at Offenbach and elsewhere in Allied-occupied Europe: to salvage Jewish culture. But, as Leff notes, France was not Germany. The decimated, dislocated, and impoverished French community remained; the communal institutions were easily restored; and, of course, the French were “the good guys.” Except that that story never sufficed where the Jews were concerned, and certainly didn’t suffice for Szajkowski, who believed the collaborationists had forfeited their custodial right to Jewish material. The more he, like others, learned about the role of Vichy, the less they liked it. His attitude toward France, ambivalent even during the war, hardened over time.

Szajkowski’s personal relationships seem to have followed parallel paths. He helped Max Weinreich collect materials for the latter’s pathbreaking work Hitler’s Professors (1946), but Weinreich eventually distanced himself from his difficult mentee. As did Arthur Hertzberg, whose seminal book The French Enlightenment and the Jews (1968), became the object of Szajkowski’s envy. Although Leff points out that Szajkowski was hardly alone among European scholars who never received their terminal degrees or never established themselves at universities, she arguably understates the gap between that debility and Szajkowski’s academic status at one point, marked by his admission into the Academy of American Jewish Research (AAJR), the ultimate marker of having made it in the eyes of peers. As Leff rightly notes, his sales to institutions such as Harvard and the Jewish Theological Seminary provided some of the basic research materials for a generation of important scholars of French Jewry. His singular imprint on the field of French Jewish history remains, possibly, more so than in any other European country, where the seminal scholars were greater in number. (With respect to Germany, this is certainly true; even with Great Britain, Cecil Roth may have been first among equals, but within a large supporting cast.)

Gallas shows the everlasting, ever-livingness of books and book lovers.

One of Leff’s many illuminating discussions treats the impact of Szajkowski’s thefts and the role of archives and archivists generally in shaping the history we tell. As she notes in her introduction, “In short, while the records on French archives are organized to reflect the organization of the French state, the records in American and Israeli documentary collections are organized to reflect the history of the Jews in the diaspora, a veritable ‘ingathering of the exiled documents.’” In French archives these were civil, communal, financial records, to be grouped according to era, place, and subject matter. To Szajkowski, these archival materials were the means to tell the Jewish story; to do otherwise would be putting the cart before the horse. How does an archive (and archivists) shape what historians sit down to recount?

This theme parallels the individual tragedy of a man, who, in saner times, would have gotten his university degree and become a distinguished professor—as many of his students and beneficiaries did. Leff’s The Archive Thief weaves this tapestry beautifully, illuminating the politics and ethics of history and memory in the process. Gallas shows the everlasting, ever-livingness of books and book lovers. Despite the tragedy that precedes her tale, my only complaint about A Mortuary of Books is its title: too dour for the accomplishments recounted within.

Ecclesiastes be damned, let us have more books like these.

University of Oklahoma