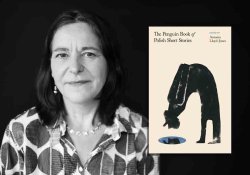

Six Decades of Visionary Imagination: A Conversation with Eleanor Wilner

Eleanor Wilner is a much-recognized member of the American literary community, long active in the practice of poetry––writing, mentoring and teaching for over sixty years. A chancellor of the Academy of American Poets and an elected member of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences, she has been awarded the 2019 Robert Frost Medal for lifetime achievement from the Poetry Society of America, a MacArthur Foundation Fellowship, a National Endowment for the Arts grant, a Pennsylvania Council on the Arts Fellowship, the Juniper Prize, three Pushcart Prizes, among many other honors. She is the author of nine books of poetry, including Tourist in Hell (2010), The Girl with Bees in Her Hair (2004), Reversing the Spell: New and Selected Poems (1997), Otherwise (1993), Sarah’s Choice (1989), Shekhinah (1984) and maya (1979). Her most recent collection, Before Our Eyes: New and Selected Poems: 1975-2017, is a canonical text that frees historically repressed voices of victims of war, racism, and misogyny.

Born in Cleveland, Ohio, in 1937, two years before the start of World War II, Wilner’s childhood was marked by the violence of that time. But her survival became the source of the transformative quality of her poetry. The speaker in her poem “Tracking” resembles the uncertain traveler of Robert Frost’s “The Road Not Taken.” Unsure of their journey, yet they “stumble forward / along the path, like one who is carrying / a message in code to a city under siege, / a city that may have succumbed / to disease, or hunger, or fire, or worse.” They continue moving, although they “have lost the path,” hoping to arrive at their destination. Wilner has made a similar journey in her defense of the sanctity of human lives and freedom against the willfulness of full-blown dictators and the capriciousness of democratic despots.

Chibueze Darlington Anuonye: Eleanor, I admire your vision of rendering myth and history in poetry. In “Daedalus, the Exile, Thinks of His Son,” the Greek mythological figure Daedalus remembers his dead son, Icarus. The story of Icarus’s death has been long framed as the narrative of an unruly child who died for his inability to heed his father’s voice. Daedalus rejects this account in the poem, insisting that Icarus was murdered because he was the son of an immigrant in Crete, an outsider among Cretans. Isn’t it fascinating how myth can speak to the present?

Eleanor Wilner: Yes. As you observe, in the way myth shape-shifts to reveal our own truths, the Daedalus of this poem, speaking from our “now,” alters the traditional narrative to make it a story reflecting the contemporary violent treatment of immigrants, and all those considered “other,” to embody the current official antipathy to their ascendance in the social, intellectual or economic world. So often, a legendary, transpersonal figure who has lived with a culture for millennia, and so carries a supercharged weight of collective meaning, can reappear to change his story, speaking out of the past to our own emergencies and crimes that include but transcend the individual. Daedalus’s release of the Minotaur at the end surprised me, since that figure had always been so profoundly liberating for me, but this was a new meaning. Perhaps the way his shadow comes “before whatever happens next” suggests how our imaginative nature sees, from present actions and crimes, the shadow of coming things and so precedes them.

Anuonye: Daedalus is firm when he says: “It wasn’t the sun” that killed my son; and piercing when he announces: “it was whose son he was, not one of theirs. / So as he circled above them, / wings spread, in the pure delight of feeling / free — / it enraged them; / and they ranted, they recoiled, they took him.” This is an eloquent indictment. Like Daedalus, the girl in “The Girl with Bees in Her Hair” represents the many in the one and alludes to the historical, political situation. In that way she, too, seems mythic. How did you imagine her?

Wilner: She is a mythic figure, one who carries a collective weight but who is new, generated out of the local air and the adaptive, recombinant energy of the visionary imagination. I can describe, but not explain, the experience of encountering her. A friend sent me a strange book written by a Swedish poet who had been ill and for months was in a coma. While in that state, unaware of the outer world, he was, in his mind, generating images that were vivid but passing, as with views seen out of a moving train’s window; images that did not cohere. One of these passing, detached images was a girl with bees in her hair.

Anuonye: The image must have endured in your mind.

Wilner: It would not leave me alone. It haunted me, and so, unable to shake it, I simply wrote, in 2001, “the girl with bees in her hair” at the top of the page and, by that mysterious poetic process in which attention to what was happening and creation of it seemed simultaneous, the description and action of the poem appeared. And who she is and what meaning she carries is best known by attending to the minute description of her, every detail of which is significant to what she might signify: her clothes, her foreign look, the ikon and its source, her bare feet. What she carries: the bees in her hair and a basket “full of flames,” which might, in its red and gold intensity, be fire or flowers, “but certainly it burned.” Then, too, the description of the great house, its scale, and the way the bees, who seemed to be happily dancing, suddenly, at the curtain’s sign of an open window, streamed out as one, “to the single opening in the high façade. A moment later, the sound of screams.”

Anuonye: Whatever brought her here left me filled with dread as the poem ends, “and the bees swarm.” What I know of the girl is only what I, like any reader, could discover by close attention, and what is most undeniable is that she is a messenger, one who walks away once her message has been delivered.

Wilner: A poem, as we both know, cannot be solved like an equation. Its eloquence is its images and actions, which carry the emotional weight of lived meaning along with the message. The bees, the fire, are what she carries, and what all this means is embodied in the poem’s action. And you know, though that fire’s burning intensity can register various things, I just thought of something I’d never thought of before, thinking of that basket of flames the girl carries in her hands—the words of Federico García Lorca, who is for me a kind of ikon for the poet. And for the way poetry by its nature opposes oppression, as his murder by the fascist falangists of Franco was one of the initiating events of the tragic Spanish Civil War of the 1930s. The words I refer to are these: Lorca was asked once what it is to be a poet. His answer: Yo tengo un fuego en mis manos—I have a fire in my hands.

The bees, the fire, are what she carries, and what all this means is embodied in the poem’s action.

Anuonye: The girl is certainly a bearer of freedom, for herself and for those who encounter her.

I realized only yesterday that you’re eighty-eight. In 2013, when I was an undergraduate in Nigeria, I told one of my professors that I would be satisfied if I lived up to the age of seventy-five. I was often ill then and tired of the anguish of ill-health. So, I decided that seventy-five was an acceptable age to leave this world. The professor, who was forty-nine, told me that at seventy-five one was still young and had so much to contribute to the world. He was right. Your life is an example that we can live meaningfully and fully till twilight. But there is also the Igbo myth of death as a transitional process of living. So, when we die, we do not stop living, we only transfer from a secular to a spiritual world, where the dead, the unborn, and the living share in the collective patrimony of life. This cultural heritage of mine explains why I am in awe of how your book Reversing the Spell combines the singularity of Judaism with the wisdom of ancient Chinese philosophies and the pageantry of modern letters to demonstrate the power of myth to shed light on the past and future of humanity. Why has myth so greatly engaged your imagination?

Wilner: I wonder if your experience may also have deepened your understanding of the human condition, your unusual degree of empathy, the way you so openly engage the work and minds of others in these conversations. And I appreciate the respect you bring from a culture that values elders. Here, we worship youth, and cosmetic surgery is a big business. But let me turn to your question: What is it about myth that has so engaged my imagination? Exposure. Myth, in my experience, is contagious; there is that within us that is awakened by it; when I encountered it, something in me that is not mine took fire from it and seemed to light the way ever since. I studied it, immersed myself in Joseph Campbell’s collections of myths, both East and West; read Jung’s theories of the collective unconscious and its archetypes, studied the apocalyptic but healing visions that arose when a communal figure of belief had been broken by conquest or colonialism; loved poets who spoke out of and dreamed for a community—and then, an unplanned event, I started writing poems.

The poems arrived, almost at once, in a “we” voice, as if arising out of a collective condition that cried for visibility and for change. It wasn’t a decision, though it became a practice, and later I came to defend it against an American mainstream culture—of the last half of the twentieth century—that derided politics in poetry and that was, to my mind, too exclusively focused on the individual and the private life, as if there was no larger world that was crucial to what was experienced as personal. Privilege does, after all, insulate people from awareness and critique of the forces that assure it. But this changed after 9/11 with what I think of as “homeland insecurity,” and with the inclusion in our mainstream literature of the voices of people of color and others who had been marginalized and fully understood how history affects all.

“If man is the measure / then man is the monster.”

Anuonye: Perhaps the 2012 anthology, The New American Poetry of Engagement, is an excellent record of this change.

Wilner: Absolutely. Students who once asked why I wrote political poems had now begun to ask me how to write them.

Anuonye: I presume that, for you, nothing is more political than myth.

Wilner: Yeats said somewhere that “we cannot know truth, we can only embody it,” and myth does precisely that: embodies insight in ancestral stories that give access to what you said of the Igbo myth––a spiritual realm where what was, what is and what is yet to be coexist and “share in the patrimony of life.” And, in the realm of imagination, myth is revelatory, partly because it disguises and protects what it reveals. Myth arises in dreams and storytelling; it is an ancestral gift that spans time and, though its stories vary with cultures, they are similar in their evolutionary, metamorphic function, rooted in past forms yet changing adaptively with time to serve new urgencies, new power arrangements, and altered conditions.

It is my experience that mythic figures, who have lived with us through time, return in times of crisis to help us change how we regard ourselves and the world, by changing the story from which they come. For instance, in a 2010 poem the Minotaur of Greek legend, who has traveled with us through time in silence, finds his voice: “I am not what you think / What you think is polluted / by what you were told / If man is the measure / then man is the monster.” So, from Western traditional monster he becomes contemporary guide, inviting us to embrace our animal nature as a way out of the labyrinth in which we had trapped and isolated ourselves. So, through the recombinant energy of the mythic imagination, a monster becomes a liberator, just as a man can become a monster created not by imagination but by what too many of us fail to imagine.

Anuonye: Failure of the imagination is one tragedy we are often unaware of. But you are a poet of great imagination, Eleanor. It is possible that the tiger in your poem “When Vision Narrows to a Single Beam of Light” is us, human beings, and that the distance previously separating us from the animal was never there. Perhaps we are just afraid of accepting the animality of our existence.

One of the values of myth is that it recalls a time when the border between human and nonhuman animals was imaginatively permeable.

Wilner: May I say that your reading of this poem delights me. For me, one of the values of myth is that it recalls a time when the border between human and nonhuman animals was imaginatively permeable, and the other animals were our first gods, before we in the West had made the tragic error to declare ourselves distinct from and superior to nature. Yes, thank you, the tiger is us. And if the double image of his connection to us is both positive––a line of light—and threatening––a burning fuse—it is that doubleness that asks for scrutiny.

I have always thought the well-known prophetic passage from Isaiah in the Bible (“the wolf also shall dwell with the lamb, and the leopard shall lie down with the kid”) was never credible as a savior undoing the natural predation among species but rather a way of reminding us about the unnatural predation of humans upon their fellow humans. The passage, as I read it, refers to ourselves, that we humans are both the wolf and the lamb, that our ferocity was meant to protect our vulnerability, and our power used to protect the weak and the innocent. I think the poem offers choices in the way the line can be read, as light or fuse, though the threatening nature of the lit fuse does suggest the approaching consequences of the abuse of power.

Anuonye: The proximity between human beings and animals is glaring. We ignore this truth at our own peril. In your poem “The Aquarium,” some tourists watch “the lustrous / cruising bodies of captive fish / that circles endlessly.” As the tourists observe this animal through a glass frame, they see their own image. It is not the fish that renders the tourists powerless but the portrait of their own faces staring at them. They realize that they are bonded with the fish in a cycle of confinement. The truth of recognition is hurtful. Likewise, in “Encounter in the Local Pub,” a similar transcendental experience occurs. A man glances at the “demonic eye of the goat” and is suddenly transported to his chaotic past. What is it about animals that troubles our imagination?

Wilner: Your reading of “The Aquarium” is so exact, so elegantly acute. Yes, the fish is like the natural life in us, separated from us, our “eyes look back at us, reflected in the glass.” Here, I think, is a double image of our isolation from our own living nature: the detachment this poem suggests is the disembodied, self-regarding world of selfies, of Facebook, our fixation on our images—and what it does to occlude and imprison the life within.

Recurrently in my poems, animals reveal us to ourselves and sometimes offer a way forward. For instance, the flight of bats vs. bombers reveals how unnatural and vile our pursuit of war is; a frog thawing out in spring embodies a promise of peace; a migrating bird becomes our biographer; in what is perhaps the poem I am most grateful to have been given, a figure from Rome’s founding legend becomes the speaker, and we learn mercy from the wolf.

And drawn from the Greek mythic imagination, carrying for me a supercharge of significance and recurring, with fresh meanings, in poem after poem throughout the years, are the hybrids: the Minotaur, half-man and half-bull, who embodies both gentleness and power and gets us out of the labyrinth, and Chiron, half-human and half-horse, with a wound that cannot heal, traditionally the teacher of the gods.

Anuonye: Before Our Eyes is a representative text of your poetic oeuvre. I imagine that the task of curating some of the finest poems you’ve published in a career that spans over five decades of active writing was both arduous and rewarding. Did you approach this book as a legacy project?

Wilner: Quite frankly, I did not think of this as a “legacy project,” which, I suspect, is because of a lifetime spent as a woman. Does that sound odd? Perhaps my age is a factor, as I grew up in a time when women’s conditioning was more traditional. But, if you’ll forgive a generalization, men seem to worry more about vanishing and invest in what seems to ensure permanence; they worry about posterity, build monuments—especially to their wars—and carve their names in stone to stand against time; women, on the other hand, in all the ages past, made what was both essential and perishable: food, cloth, and life. But they also lived in a great public silence, mostly excluded from literature and the value it confers on the life it records. I think of this as the Great Silence, of women and of all the excluded, the anonymous many, from which these poems often seem to arise.

So, despite my personal reticence, because the poems are not my possessions and are meant to be shared, I have seen to their publication. I arranged the selections from books in reverse chronological order, so, for anyone interested in the unfolding of interior vision, through myth and natural imagery on a historical timeline, they are probably best read from back to front. I chose the poems that were the most “given,” that surprised me the most, and that, for me as for any reader, the awareness of their meaning came slowly and after the fact. As James Baldwin said, “when you’re writing, you’re trying to find out something which you don’t know . . . what you don’t want to know, what you don’t want to find out. But something forces you to, anyway.”

The earlier poems, from the first, spoke in the “we” voice, often giving voice to silent or minor characters from traditional stories, and through them explore what, at our cost, we have been silent about, hidden from ourselves in a haze of fictional national exceptionalism. Or what has been hidden from us by those who would control us, as in a 1984 “Ars Poetica,” that opens the forbidden door in Bluebeard’s palace where misogyny hangs its trophies, the murdered brides of history: “the wind that makes them sway until/ they seem almost alive, is like the rush of our compassion.” But awareness comes from the poems, not before them. I have never had a conscious project or a plan for the poems, the way you do for a class or a lecture. Poems have a mind of their own; everything and anything gets into them, but not by design.

Poems have a mind of their own; everything and anything gets into them, but not by design.

A poem, in my experience, starts with an itch, an image, a sound, a line from someone else’s poem, a mythic figure––never with an idea. What releases and carries the vision is the gorgeous echoic music of language, the way its patterns open the imagination and quiet the censorious ego. Truth is made tangible and palatable, not just by its revelatory metaphoric disguises, but by its beauty. In the words of Toni Morrison to which I adhere: “Make it political as hell, and make it irrevocably beautiful.” Poetic imagination includes, of course, the intellect, but not as planner, not as master—as it might wish—but as servant of the whole being: a kind of successful palace revolution that doesn’t harden the pharoah’s heart but loosens his tongue, lets his sympathies stray, the gardens flourish, and open to all, the waters flow and the fountains play.

The newest poems in this collection, written between 2011 and 2017, shift their subjects and moods, some are—because of my age—retrospective, while others are topical and warn, recoil at and partly reveal the coming home of what we, in arrogance, had mainly exported, leading to the current open embrace and empowerment of what is worst in us. Since our popular films, media, and entertainment have accustomed and inured us to brutality, injustice, and atrocity, the poems refuse to enact that violence but, rather, make desecration real by dramatizing the value and sacred nature of what has been or is being destroyed.

An earlier poem, “Classical Proportions of the Heart,” written in 1989, poses a question in the context of the Greek tragedy Oedipus Rex; it asks of the disobedient servant who rescues the infant put out to die by his father, Laius the king: “What brief can he make for mercy in a world that Laius rules?” Laius is every ruler who has put the future out to die from his own fear of death and replacement. If there is a question that runs, like an underground stream, through these poems, this might be it.

Anuonye: This is a legacy, Eleanor.

Wilner: If you say so, Chibueze.

Anuonye: And, yes, I forgive your generalization about men, which is mostly true.

Wilner: I was sure you would.