The Weight of Remembering: On Yang Jisheng’s History of the Chinese Cultural Revolution

The year 2021 marks the centenary of the founding of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). In April, the CCP released the latest edition of A Brief History of the Communist Party of China, in which the chapter dedicated to the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976) disappears. This latest edition touches on the Cultural Revolution in no more than 13 pages in another chapter entitled “Twists and Turns on the Road to Socialist Reconstruction.” It glosses over Mao Zedong’s mistakes, simply stating that Mao had waged “an incessant war on corruption, special privileges and bureaucratic mentality within party ranks. … Many of his correct ideas about how to build a socialist society weren’t fully implemented, which led to internal turmoil.”

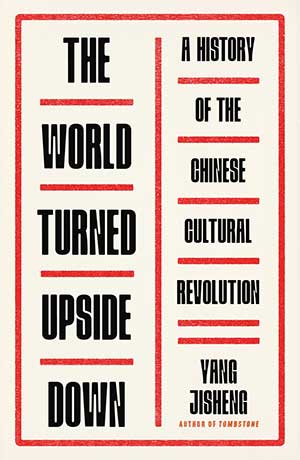

This year also marks the publication of the abridged English translation of Yang Jisheng’s The World Turned Upside Down: A History of the Chinese Cultural Revolution, translated by Stacy Mosher and Guo Jian (Farrar, Straus and Giroux). The book contains 29 chapters and 768 pages. In the words of WLT editor in chief Daniel Simon, it looks like “a door stopper” by virtue of its size and weight. The original Chinese version of The World Turned Upside Down (Tianfan Difu), which was first published in Hong Kong in 2016, is weightier, containing 32 chapters and 1,069 pages.

This year also marks the publication of the abridged English translation of Yang Jisheng’s The World Turned Upside Down: A History of the Chinese Cultural Revolution, translated by Stacy Mosher and Guo Jian (Farrar, Straus and Giroux). The book contains 29 chapters and 768 pages. In the words of WLT editor in chief Daniel Simon, it looks like “a door stopper” by virtue of its size and weight. The original Chinese version of The World Turned Upside Down (Tianfan Difu), which was first published in Hong Kong in 2016, is weightier, containing 32 chapters and 1,069 pages.

The sharp contrast between the 13-page official narrative and the 1069-page comprehensive account of the Cultural Revolution is telling of the brutal battle over the narrative of history, especially the history of the CCP, in contemporary China. In her new book Negative Exposures: Knowing What Not to Know in Contemporary China, Margaret Hillenbrand discusses contemporary China’s culture of “public secrecy” that prevents people from remembering and making sense of the major events in Chinese history in narratives outside of those endorsed by the state. Yang’s personal endeavors to narrate the Great Chinese Famine (in his 2008 award-winning book Tombstone) and the Cultural Revolution have been viewed as dissident acts by the Chinese authority, who not only banned the books in China but also prohibited Yang from traveling to the US to receive the Louis M. Lyons Award for Tombstone in 2016.

Despite the enormous political pressure of keeping the public secrecy in China, Yang Jisheng spent nine years researching the complex and dangerous terrain of the Cultural Revolution and completed this weighty book. The weight of the physical book corresponds to its moral weight: the author believes that it is our moral duty to remember the Cultural Revolution in all its aspects, not just for China, but also for the sake of human history.

Yang’s personal experience and previously held positions make him an ideal chronicler of the Chinese Cultural Revolution. Yang joined the Chinese Communist Party in 1964, became a Red Guard at Tsinghua University in 1966 and traveled across China to network with other revolutionary Red Guards between 1966 and 1967, worked for the state-run Xinhua News Agency between 1968 and 2001, and served as the deputy editor of the official journal Chronicles of History (Yanhuang Chunqiu) between 2003 and 2015. In addition to engaging with an impressive array of historical archives, government documents, news reports, biographies, and memoirs, Yang’s book also offers a unique insider’s perspective, firsthand experience, a journalist’s sensitivity, and a sober understanding of the Cultural Revolution. To date, The World Turned Upside Down remains the only complete history of the Cultural Revolution by an independent scholar based in mainland China. It is a must-read for anyone looking for an in-depth understanding of modern China’s biggest cultural and political revolution.

The World Turned Upside Down is a must-read for anyone looking for an in-depth understanding of modern China’s biggest cultural and political revolution.

Yang narrates the Cultural Revolution as “a triangular game between Mao, the rebels, and the bureaucratic clique” (xxviii). In socialist China, a totalitarian bureaucratic system was formed during the first seventeen years following the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949. Although this system was established by Mao, it took on a life of its own and was not entirely dominated by Mao. In order to carry out a massive struggle against the bureaucratic clique, Mao connected himself directly with the lower-class masses, mobilizing the latter to roast the bureaucracy. However, at the same time, Mao could not let the revolutionary rebels throw the nation into permanent anarchy, so he also sought the bureaucrats’ help to restore order. The ten-year turmoil of the Cultural Revolution registers Mao’s vacillation between pursuing his utopian ideal of a classless society and his intrinsic need for social order.

The ultimate victors of the Cultural Revolution were the bureaucrats, who, after Mao’s death in 1976, controlled the official narrative of the Cultural Revolution, purged their political opponents (the rebels), led the nation back to a new wave of privilege and corruption, and created a polarized society through a “power market economy,” where “abuse of power is combined with the malign greed for capital” (xxxii). In other words, because the Chinese masses failed to win the Cultural Revolution, today’s China is an unfair society that can never be harmonious.

Yang’s narrative of the Cultural Revolution is decisively different from the popular narratives both inside and outside of China. As Xueping Zhong points out in her review of Barbara Mittler’s A Continuous Revolution, those prevalent narratives have often likened the Cultural Revolution to “Nazi Germany, racist America, Soviet Gulags, ‘feudal’ Chinese court intrigues, traditional ‘Chinese cruelty’, and so on.” Yang presents the Cultural Revolution rebels as cohorts of idealistic young Chinese who ardently experimented with political democracy and social equity following the precedent of the Paris Commune. According to Mao’s blueprint, continual revolutions were needed to correct the selfish human nature and eliminate the social division of labor. Those revolutionary rebels were not innocent, and it was not long before they encountered strong resistance from the bureaucrats and became victims of the Revolution, as Yang writes: “The rebel faction was indeed savage and cruel when it had the upper-hand, but these periods covered only two years of the Cultural Revolution, and those who suppressed the rebels during the other eight years were even more savage, while the rebels were more brutally purged after the Cultural Revolution” (230). In addition, there were divisions and internal struggles within the rebel faction, and Mao parted with the rebel faction in 1968, leaving his most ardent followers under attack by the bureaucrats.

In Yang’s corrective narrative, the Cultural Revolution finally ceases to be an abstract idea or an exotic spectacle—it is represented as human history.

Yang’s book can be read as an encyclopedia of the Chinese Cultural Revolution. The 29 chapters in the English edition are organized chronologically; but in most chapters the author documents the uneven developments of the Cultural Revolution in multiple locations all across China. Such a writing style resembles the viewing of the traditional Chinese scroll painting: the author does not occupy a fixed position but rather constantly moves about to focus on a specific part or event of the revolution, in order to provide a more accurate and truthful representation of the complex history. Yang thus weaves a panoramic scroll painting of the Cultural Revolution, which consists of millions of active or passive players and thousands of power struggles. Yang’s history makes sense of every character’s action and every event during the Cultural Revolution. Such close focus and making sense of the historical characters and historical events are important, because through them the Cultural Revolution finally ceases to be an abstract idea or an exotic spectacle—it is represented as human history in Yang’s corrective narrative.

Every word in The World Turned Upside Down carries the moral weight of remembering, an act of remembrance that proves even more valuable in the present era.

Every word Yang Jisheng pens in The World Turned Upside Down carries the moral weight of remembering, an act of remembrance that proves even more valuable in an era in which thought, truth, and economic resources are unexceptionally monopolized by the Establishment across the globe. The Cultural Revolution is a bitter memory in human history. It shows us, in Herbert Marcuse’s words, “the unhappy consciousness of the divided world, the defeated possibilities, the hopes unfulfilled, and the promises betrayed.”[i] However, the memory of the Cultural Revolution is valuable precisely because of this: it saves us from a suffocating complacency with the present, it tells us that established norms can be challenged, and it begs us to imagine an alternative future and act on it.

University of Oklahoma

[i] Herbert Marcuse, One-Dimensional Man: Studies in the Ideology of Advanced Industrial Society (Routledge, 2002), 64.