Attar, the Sufi Poet and Master of Rumi

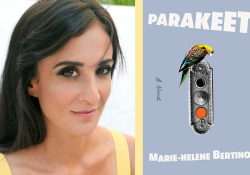

Attar’s The Conference of the Birds, just released in a new translation, is a deeply meaningful and spiritual work, delightfully packed with lively banter, pathos, clever hyperbole, cheeky humor, poetic imagination, and surprises. Translator Sholeh Wolpé invites readers to join the poet on his “journey toward the unfathomable Divine.”

Muslims invaded Iran in 637 CE. The Islamic conquest ended the Sassanid Empire and led to the eventual decline of the Zoroastrian religion in Iran. Even though the majority of Iranians eventually converted to Islam, many aspects of their ancient civilization became integrated into the newly formed Islamic society.

Through the following centuries, the fluctuating relationship between freethinkers and those who followed strict religious dogma profoundly affected the development of poetry in Iran. Whenever the kings or governors were influenced by religious leaders, philosophy and poetry became stunted and the realm of ideas darkened. However, when the sovereigns established a closer relationship with philosophers and poets, enlightenment inevitably followed.

Attar, Sheikh Farīd-Ud-Dīn (1145-1220), فرید الدین عطار , was born in Nishapur (Nīšāpūr), a city in the northeast region of Iran. Information about Attar’s life is scarce and has been mythologized over the centuries. However, what we do know for certain is that Attar practiced the profession of pharmacist and personally attended to a very large number of customers.

The extent of Attar’s initiation into Sufi practices and mysticism is the subject of many speculative, sometimes fabricated tales. Some believe that he was reared in Sufism. Others speculate he was so moved by the troubling stories his patients shared with him that he abandoned his pharmacy and traveled through India, Turkistan, Mecca, Kufa, and Damascus to seek wisdom from Sufi saints. Still others tell of his conversion to Sufism. One such story tells of a wandering dervish who came into Attar’s shop and asked if Attar could die as a dervish could. Attar replied, Of course I can. The dervish then invoked the Divine, put his head down, and died right there and then. Attar was so moved by this act of power and devotion that he immediately closed his shop and began his travels searching for Sufi masters.

Sufism is a spiritual philosophy, and all human beings, regardless of their faith and religion can come to feel its ecstatic influence on their soul. The central idea in the Sufi movement is that the soul, in the prison of the body, awaits release. Once freed, it returns to the source, which is the Creator. This reunion can be experienced while we are still bound by the body through looking inward and through purification.

Legend has it that Attar met Rumi when that future great mystic poet was a child. Rumi’s family was traveling west to stay ahead of the Mongols. It is said that Attar held Rumi in his arms, bounced him on his lap, and predicted his greatness. Rumi went on to become a beloved Sufi poet with devoted fans and followers. He repeatedly acknowledged Attar as his master, and the influence of Attar’s wisdom and style of writing is evident in Rumi’s work. About Attar, he wrote:

Attar traveled through all the seven cities of love

While I am only at the bend of the first alley.

Attar’s death, as with his life, is subject to speculation. He is known to have lived and died a violent death in the massacre inflicted by Genghis Khan and the Mongol army on the city of Nishapur in 1221, when he was seventy years old.

Of the forty works bearing Attar’s name, approximately seven are verifiably his, including The Conference of the Birds, which he completed around 1187 when he was about forty years old. The epic poem is a masnavi, a poetic form invented by the Persians. It adheres to a meter of ten or eleven syllables per line, in rhyming couplets. The Conference of the Birds consists of a total of 4,724 couplets, including the prologue and the epilogue.

The story begins with the birds of the world gathering together to seek a sovereign. The wisest of them, the hoopoe, suggests they undertake a journey to the court of the great Simorgh, a mysterious bird who dwells in Mount Qaf, a mythical mountain that wraps around the world, where they can achieve enlightenment. The birds elect the hoopoe as their leader for the quest. At the start, each bird presents an elaborate excuse for not being able to make the journey, but the wise hoopoe addresses their many hesitations, complaints, fears, vanities, and questions. For example, here is a parable the hoopoe offers about faultfinders:

Parable of the Blemish in a Beloved’s Eye

There once was a lion heart, a vanquisher of enemies, who loved a woman for five years. This lovely woman had a blemish as small as the tip of a fingernail in one of her eyes. The man never saw this white blemish, even though he gazed into her eyes all the time. How can a man so deeply in love notice a fault in the eye of his beloved?

After a while, however, love cooled in the man’s heart like a sickness calmed by medicine. His love for the woman waned and he no longer felt the pain of love. That’s when he noticed the deformity in her eye and asked: “When did that blemish appear in your eye?”

She replied: “The moment your love for me began to die. When your love faded, so did the perfection of my eyes.”

Conniving, suspicious, unkind heart,

look at your own faults, don’t be blind.

How long must you go on pointing out flaws in others?

It’s high time to catalog your own vices.

Start keeping tab on your own shortcomings

and you won’t have time to find fault in others.

Eventually, the birds prepare themselves and take off toward the abode of the Beloved, the Great Simorgh, but most perish on the way and only thirty make it to the great court. After they are received, cleansed of their egos, the birds learn that they themselves are the Simorgh; the name “Simorgh” in Persian means thirty (si) birds (morgh). They eventually come to understand that the majesty of that Beloved is like the sun that can be seen reflected in a mirror. Yet whoever looks into that mirror will also behold his or her own image.

We are the birds in the story. All of us have our own ideas and ideals, our own fears and anxieties, as we hold on to our own version of the truth. Click to Tweet

Click to Tweet

We are the birds in the story. All of us have our own ideas and ideals, our own fears and anxieties, as we hold on to our own version of the truth. Like the birds of this story, we may take flight together, but the journey itself will be different for each of us. Attar tells us that truth is not static and that we each tread a path according to our own capacity. It evolves as we evolve. Those who are trapped within their own dogma, clinging to hardened beliefs or faith, are deprived of the journey toward the unfathomable Divine, which Attar calls the Great Ocean.

The Conference of the Birds is a deeply meaningful and spiritual work that is delightfully packed with lively banter, pathos, clever hyperbole, cheeky humor, poetic imagination, and surprises. The parables are not meant to simply instruct; they are also meant to be enjoyed. This is an important aspect of the work that must be reflected in the way it is re-created as English. The element of entertainment must be maintained, and that requires accessibility and readability as well as poetic beauty. As translator, in the spirit of re-creating Attar’s ageless masterpiece into the readable and entertaining work it was in its own time, I have shunned all academic austerity in favor of poetry.

Some language shifts and line movements were necessary in order to achieve an accessible translation, which makes adherence to a strict line-by-line translation impossible. The parables, smoothly connected, orbit around a central theme. Therefore, I re-created the parables as poetic prose and the speech of the birds and of Attar as contemporary verse. In this way, the work is rendered readable not only as a deeply spiritual work but also as a form of entertainment, as Attar intended it to be.

When the heart busies itself with trivial nothings,

nothing will come but boredom and redundancy.

Abandon your ego, cast off your vanity.

How long do you think your life’s ocean will surge?

Give in, relinquish your soul;

then hush, be at peace.

Los Angeles