Drifts of an Arab Boat in the Sea of Translation for Children

The following essay has been adapted from the author’s Arabic-language version under the same title. The Arabic essay will be co-published by the Abu Dhabi International Book Fair and Al-Ittihad newspaper, United Arab Emirates (May 7–13, 2015).

Dear Reader,

I invite you to take a one-minute journey in which you return to your childhood and reach for a bookshelf that has the title of a translated story which affected you when you read it as a child. What language was it translated from? What was the theme?

For me, I grew up in Palestine, speaking Arabic. The non-Arabic books that expanded my world included Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea, with its main character, Santiago. Even though he and his journey were fictional, even though decades and cultures separated us, I felt that I experienced everything Santiago went through. He affected me more than many people I could look in the eye, and with whom I could speak.

Gulliver’s Travels, Sleeping Beauty, and Cinderella were among the other translated books that I read. Without the immense generosity of translators, and their courage and ongoing vision to create meeting places where nations exchange the value of the written arts, I would not have known these powerful tales. I feel that the art of translation should have a nickname: “trans-nation.” And I dream that, some day in the future, there will stand at every border between countries a statue called “the translator,” one who helps make human otherness less of a foreign land, less of a threat, and more of a self-exploration as the definition of the self grows and embraces more and more, without the fear-based desire to dominate others.

I dream that, some day in the future, there will stand at every border between countries a statue called “the translator.”

As a young reader, my appreciation for translated stories rested strongly on my knowledge of comparable Arabic literature. The resonance gave me the cognitive ground to stand on. I could go far and explore only because my mother tongue could be heard singing nearby, ready to provide an ongoing sense of confidence.

I understood The Old Man and the Sea through my love for the journeys of Sindibad, who is known in the West as Sinbad. This fictional sailor from Baghdad constantly took voyages, faced struggles, and triumphed. While reading I would sneak into the back of his boat and travel with him. I tried to help him through hardships, only to discover that I was holding a paper boat—while far away from sea, a child reading a book.

And Gulliver, who was tied down by the miniature people, the Lilliputians—I understood him through Uglat al Usbaa, the character in Arabic literature whose height measures half a thumb, and also another miniature Palestinian folk hero named Nus Insais. These cherished fictitious people fit the sensibility of the physical world of a child. They make a child feel understood and safe. They allow for empathy with the child who struggles to grasp the language of adults in order to accomplish a sense of belonging. They translate the world for him, in a child-sized font.

And I entered the world of Cinderella and Snow White through the story of Jbaineh, the girl whose complexion is white as goat cheese. While on a journey, Jbaineh loses her home.

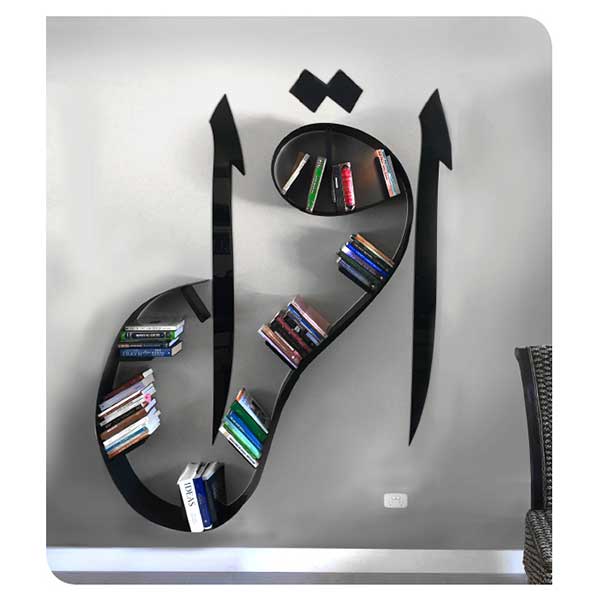

in her office. It is a letter to both Arabic and English, and the

message is the clock with both Arabic and English letters; the

shape of the English letter I is the same as the letter alif in Arabic.

The sentence “I love you” in both languages covers all the numbers.

So, reading translated literature as a young reader strengthened my belonging both to my own Arab culture and to the culture of the world.

Recent findings relating to studies of second-language learning support that a strong foundation with the mother tongue facilitates higher mastery of new languages. Without a sense of home in oneself, a young reader could feel alienated and foreign anywhere.

That is why I differentiate between the translation of external language and the deeper translation of the vibrant feeling and thought embodied in the unique radiance of a certain culture as it is rooted in the history, shape, and system of meaning native only to it. This is what I see as “rooted translation,” alive as a tree in a forest, tall and swaying fluidly with the winds of meaning.

This requires courage, humility, and the suspension of judgment as we enter the culturally unfamiliar. Not understanding a culture does not reflect on that “foreign” culture but, rather, on our limited understanding of it due to lack of interest, fear, prejudice, or any other reason. The challenge is ours to expand, rather than for that culture to change and fit where we stand at the moment. Rooted translation is necessary also because one cannot comprehend from the outside what dwells deeply on the inside. . . .

When reading what is not “native,” one benefits by keeping in mind that any word can become a massive experience—big as a country, vast as an entire people. It might also appear as a major challenge. You now, versus the you after the new understanding. So beware; be-aware; be a-wake as you blossom while drifting into the mysterious universe of culture, word, and story. Do not miss any details of the present as it arrives wrapped in foreign accents. Let it open you up to a new sense of wider belonging.

To gather, which is the first act of worship in Islam—supported by a later command to go out and meet people, get to know them, and let them know you—requires much translation.

As a teenager, my interest in translated literature grew when I understood how the Arabic language is the mother of Islam, but Islam, as a fast-growing religion, ensures the continuation of Arabic. The first command in Islam’s holy book is Iqra’! Read! And to read in Arabic means to gather. The Qur’an is the book that gathers stories and meanings. And to gather, which is the first act of worship in Islam—supported by a later command to go out and meet people, get to know them, and let them know you—requires much translation.

Therefore, when reading translated stories, a child anywhere can grow in perspective. Translated literature for a child can affirm a sense of shared humanity as it is innocently evident in childhood: children across the planet are more alike than different. Most learn quickly. Most love openly. They are mostly courageous. They put things in their mouths, perhaps in a foreshadowing behavior pointing to the symbolism of language and sound as they are born from the mouth of the individual announcing the communication journey as the core of the social experience.

Translated literature for a child can affirm a sense of shared humanity as it is innocently evident in childhood: children across the planet are more alike than different. Most learn quickly. Most love openly. They are mostly courageous.

Two children growing up in different countries know different information. Each is in her world. They go to schools in lands speaking different languages. But they also look at the moon, which needs no translation. Both wonder at the magic of this orange balloon.

The moon in Arab culture is masculine, but in Latin sensibility it is feminine. The Western child can celebrate that current science allows people to land on the moon and explore space. The Arab child can celebrate that more than two hundred heavenly bodies, including stars, planets, and constellations, carry Arabic names because the early Arabs charted the sky with great passion and close observation. Maybe neither knows that an Arab geologist, Dr. Farouk El-Baz, assisted in the preparations for the Apollo missions, including choosing the landing sites on the moon. And most people in the world own phones. They dial using the Arabic system of numbers.

So, I envision a new movement of human literacy where the picture of humanity is integrated and the contributions of all nations and peoples are acknowledged. The body of humanity as well as the body of the world’s literature need the eyes and the fingers and the feet and the back and the nose and the heart. If you understood that humanity is one body, and that literature of the human experience is one body, would you opt for cutting off a part?

Ongoing investment in translation can help the world open up the mind’s gates for greater appreciation and respect for others and for the self. The need for cross-cultural appreciation and cooperation to solve problems and accomplish humanity’s dreams, even though often dismissed, remains an urgent necessity.

Consider health, for example: everyone agrees that it does not matter where the cure for a malady comes from. People across the planet seek the effective medicine that saves lives. Respect, kindness, cross-cultural appreciation, and increased understanding can save equal numbers of lives, if not more. The countless people, plants, animals, lands, and water bodies that are harmed due to many wars fueled by lack of cross-cultural empathy and compassion can be spared such unspeakable pain. Literature, translation, and an expanded understanding through languages are among humanity’s greatest medicines. We can begin building these healing values starting in childhood.

Editorial note: M. Lynx Qualey’s recommended “Arabic Books for Teens” appeared in the January 2014 issue of WLT, which also featured two audio poems by NSK Prize-winner Naomi Shihab Nye as well as Ibtisam Barakat’s tribute poem, “Table of Continents.”

For Further Reading

The International Board on Books for Young People (IBBY) is a nonprofit organization that represents an international network of people from all over the world who are committed to bringing books and children together. IBBY’s Hans Christian Andersen Awards are the highest international recognition given to authors and illustrators of children’s books; click here to view the 2016 nominees. Also, the IBBY Honour List is a biennial selection of outstanding, recently published books honoring writers, illustrators, and translators from IBBY member countries.

Since 2003, the NSK Neustadt Prize for Children’s Literature has enhanced the quality of children’s literature by promoting writing that contributes to the quality of their lives. Ibtisam Barakat nominated laureate Naomi Shihab Nye for the NSK Prize in 2013. Ghanaian author-illustrator Meshack Asare is the 2015 prizewinner.

The Mildred L. Batchelder Award is given to the most outstanding children’s book originally published in a language other than English in a country other than the United States, and subsequently translated into English for publication in the United States. The 2015 winner and honor books can be found here.