Nobody Sees Us: The Poetry of Humberto Ak’abal

For nearly a decade I ran a visiting writers series at a liberal arts university in Indiana. The series was very well endowed, which meant that we didn’t have to hold bake sales to attract the biggest names to campus. I had the opportunity to wine and dine and introduce at the podium Salman Rushdie, Joyce Carol Oates, Seamus Heaney, Mary Oliver, Robert Bly, E. L. Doctorow, Zadie Smith, Neil deGrasse Tyson, and many others. Yet the best reading came from a poet who is virtually unknown in the United States and who does not even speak English.

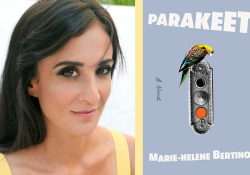

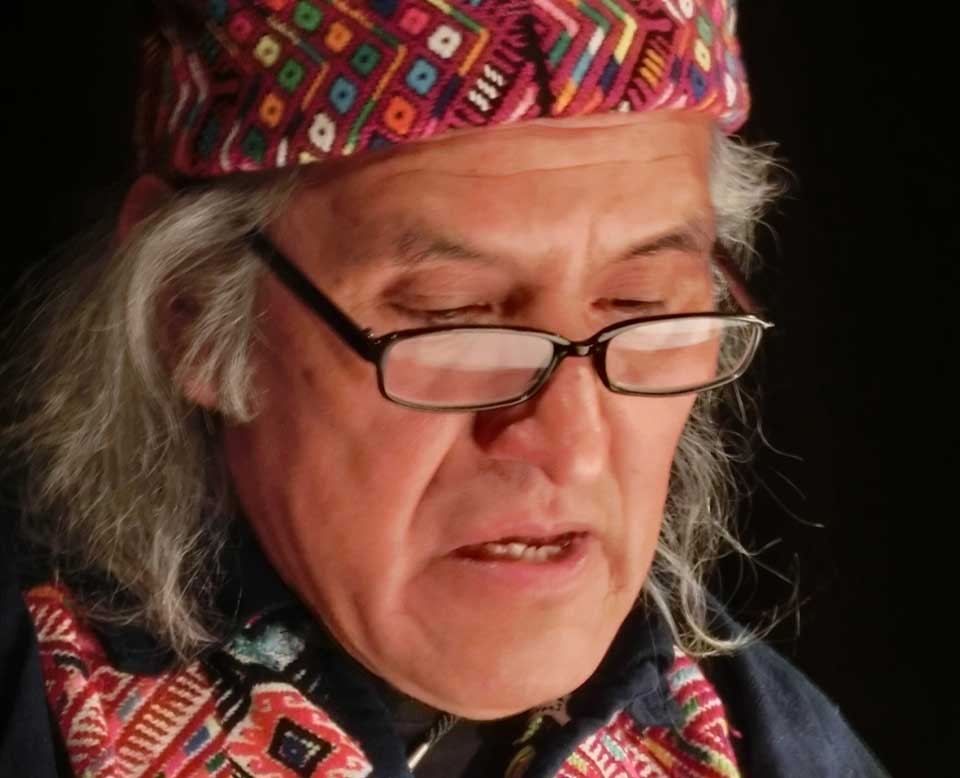

Humberto Ak’abal is a Maya K’iche’ Indian who writes in his native K’iche’ and in Spanish. Incidentally, there is no word for “poet” in the K’iche’ language; he is called “singer.” When he recited his poems to an audience of mostly Caucasian middle-class midwesterners, something happened that I had never before or since witnessed at a poetry reading. The audience didn’t levitate; rather, the floor sank beneath us, leaving us standing about three feet above it. And this was before the poems were understood; before his translator, the great musician and storyteller, Miguel Rivera, followed with his English translations.

I am not sure how to interpret this. Perhaps it is analogous to the proverbial rug being yanked from beneath one’s feet, as if what we thought we knew that kept us grounded was no longer there, leaving us to reevaluate “where we stood.”

When I was about fifteen, a construction crew was tearing up the street I grew up on to get at pipes or something. I noticed a layer of brick several layers beneath the asphalt, which revealed a history I didn’t realize existed. I lived at the top of a steep hill. My father explained that the bricks were laid in the early part of the twentieth century to provide traction for horses and automobiles with barely the power of twenty horses. Hearing this made me feel connected to a bygone era.

Ak’abal has tapped into the substratum of his land and its pre-Columbian history through poems that are as palpable as the mountains and canyons and the stories they tell.

Ak’abal has tapped into the substratum of his land and its pre-Columbian history through poems that are as palpable as the mountains and canyons and the stories they tell. His poems reconnect to the sacredness in nature. One can feel it in its original language. He explains that onomatopoeia “sprinkles” the tongue of his ancestors: “This is a language that does not go to the senses but to the spirit.” Here is the final stanza of “Kinrayil, Kawaj” (“Quisiera”/ “I Would Like”):

Kinrayij kinb’an tz’ikin,

kinrapinik, kinrapinik, kinrapinik

xuquje’ kimb’ixonik.

sib’alaj utz kina’o kinb’an ri nukis

puwi’ kib’ oxib’ sutaq’

xuquje’ nikyaj sutaq chik.[i]

And we listen and absorb and are transformed—not into something but from something—until we forget where we stand (spiritually, figuratively, physically, and emotionally).

And the log

listens

consuming himself

until he forgets

he was once a tree.

But we can never forget the pain and suffering: “And to each one / he gives a shadow.”

Perhaps the floor’s submergence was an invitation to fly. This is hyperbole, of course, but Ak’abal, standing at the edge of a ravine with his mother, writes with absolute sincerity, “I was waiting for the moment / to throw myself into flight.” We, the audience, were not equipped to recognize the overture because we were held down by the very institution that hosted this event.

Blackbirds, buzzards, and doves

land on cathedrals and palaces

just as they do on rocks,

trees, and fences . . .

and they shit on them

with the complete freedom of one who knows

that god and justice

belong to the soul.

Ak’abal does not have an MFA. He left school at age twelve to work with his father, weaving the heavy woolen blankets for which his hometown of Momostenango is famous. This is a foreign concept to poets in the United States. Generally, poets will go straight from undergraduate studies into one of the many MFA programs and have their poems workshopped. They become, either by pressure or ambition, obsessed with publishing and being known.

Ak’abal says that when he is looking for the right word, he does not go to the dictionary but to the marketplaces, the village squares, the streets.

Ak’abal says that it was a particularly prescient dream that “woke up” the poetry in him. “To walk, dig, wait, is simply the process that takes me to the writing of a poem.” Ak’abal says that when he is looking for the right word, he does not go to the dictionary but to the marketplaces, the village squares, the streets. “I look / for a sign from another time,” Ak’abal writes, “something to take me / to the lost voice of my ancestors.”

The writing of a poem must be a need or impulse. Ak’abal writes from this need.

When I was born

two tears were put

into my eyes

so that I could see

the enormity of my people’s pain.

I don’t know many living poets who look for, let alone see, people’s pain.

Ak’abal’s visit to our modest campus was less than a month after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. A student asked what the people of Guatemala thought of the attacks hoping, no doubt, for sympathy and solidarity. Ak’abal responded that, while they were sympathetic to our suffering, the people of Guatemala were simply not impressed by our shock and dismay. He pointed out that they witnessed and experienced this kind of terror on a daily basis, alluding to the systematic torture and murder of two hundred thousand people, the vast majority of them Mayan Indians, in which the US government bore a major responsibility.

This is not taught in schools in the United States. Students are usually stunned to learn that the US government had a role in Central America by arming and training military death squads. This led to a thirty-year civil war, military dictatorships, and the deaths of tens of thousands of indigenous people through a policy of genocide. This is especially relevant today as we watch the separation of children from their parents who are seeking asylum at the border.

Ak’abal’s is a poetry of contraconquista (counterconquest), which is a way of not submitting to conventions defined by the dominant culture.

Ak’abal’s is a poetry of contraconquista (counterconquest), which is a way of not submitting to conventions defined by the dominant culture. “I say things how I feel them, how I live them, how I see them: with freedom.”

They have stolen from us

lands, trees, water.

What they have not been able

to possess is the nawal.

They never will.

The nawal means both “K’iche’” and “spirit.”

One year prior to his visit to our quiet city among cornfields, Harper’s magazine ran an article on dying languages in which Ak’abal was reported to have been killed in an automobile accident.[ii] After bringing Ak’abal to Indiana, I wrote to Harper’s of their erroneous claim. I informed the editor that not only was I able to shake his hand, but that he moved many of my students to tears by his poems in this dying language. No response; only a single sentence at the bottom of the copyright page of a subsequent issue: “We regret the error.”

Humberto Ak’abal is not dead. He is alive and well. His poetry is alive and well. He is singing an indelible song to remind us.

The flame of our blood burns

inextinguishable

in spite of the wind of centuries.

We do not speak,

our songs caught in our throats,

misery with spirit,

sadness inside fences.

Ay, I want to cry screaming!

The lands they leave for us

are the mountain slopes,

the steep hills:

little by little the rains wash them

and drag them to the valleys

that are no longer ours.

Here we are

standing on roadsides

with our sight broken by a tear . . .

And nobody sees us.

Editorial note: Ak’abal recited bilingual versions of several poems for the journal La Otra on the occasion of the Feria de las Culturas indígenas y barrios originarios de la Ciudad de México in 2018.

[i] “How I would like to be a bird / and fly, fly, fly / and sing, sing, sing / and shit—with pleasure— / on some people / and some / things!” (103).

[ii] Earl Shorris, “The Last Word: Can the World’s Small Languages Be Saved?” Harper’s Magazine (Aug. 2000): 35.