From Andy Warhol’s America to Fantasy America: A Conversation with Curator José Carlos Diaz

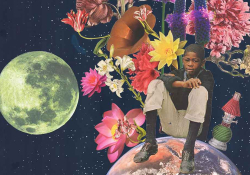

2019, courtesy of the artist and Two Palms, © by Nona Faustine

In Fantasy America, a new exhibit at The Warhol, five cross-disciplinary artists offer a complex picture of American life indelibly tied to this tumultuous moment of political upheaval and social reckoning. Here, José Carlos Diaz, chief curator at The Warhol, discusses how Warhol’s 1985 book, America, inspired the exhibit and how the work of these contemporary artists develops the exhibit’s theme. The exhibit runs through August 30, 2021.

Michelle Johnson: The first line of Andy Warhol’s 1985 book of photographs and commentary, America, reads: “Everybody has their own America, and then they have the pieces of a fantasy America that they think is out there but they can’t see.” How did this book spark the current exhibit at The Warhol?

José Carlos Diaz: The first passage of this book was the seed for the show. The full description has Warhol describing growing up in Pennsylvania and imagining what the rest of the country is like based off what you think it might be. The rest of the book includes more text but also offers extensive photos from the last decade of Warhol’s life. Much of it looks and feels like the book came out in 2020. I wanted to explore ideas about America but with living artists and exploring their practice.

Johnson: Fantasy America is an exhibit with contemporary social justice themes. When I recall my visit to The Warhol, or other Warhol exhibits, images of celebrities first come to mind. Likely, other people think of soup cans. I was on Zoom with a lawyer yesterday who has Warhol-imaged skateboards decorating his office. How do we get from Warhol to Black Lives Matter?

Diaz: Warhol depicted current events as they happened as well as contemporary life. Beyond soups cans you can look at his depictions of suicides, the atomic bomb, the assassination of JFK, civil rights protesters being attacked by police dogs, and capital punishment through his electric chair series, for example. This new exhibition is about contemporary life today, and the artists in the show are responding to their lived experience, not Warhol’s.

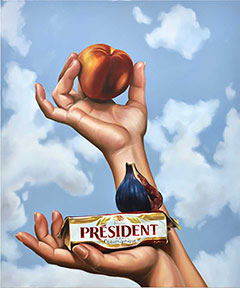

courtesy of the artist, © 2020 by Chloe Wise /

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Warhol depicted current events as they happened as well as contemporary life.

Johnson: There are five contemporary artists in Fantasy America. How does each of their work develop the theme of the exhibit?

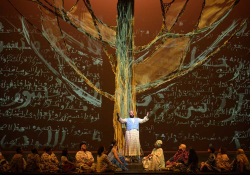

Diaz: Nona Faustine confronts modern injustices through photography centered on public monuments and civic buildings that relate to hidden African American histories. Kambui Olujimi addresses nationhood and the colonization of bodies, land, time, and space, surfacing buried political pasts. Pacifico Silano collages vintage gay men’s magazines to explore love and loss in queer culture and community. Naama Tsabar uses her body and sound compositions to perform outside the boundaries of gender norms with an array of female and gender-nonconforming collaborators. Chloe Wise deconstructs advertising and audience through staged narratives to reveal tenuously manufactured social contracts and constructs.

Johnson: Nona Faustine’s In Praise of Famous Men No More is from a series, My Country, that interrogates iconic American monuments, including the Statue of Liberty and the Lincoln Memorial. In America, Warhol writes of DC tourists’ pride upon encountering Lincoln’s statue or the Vietnam Memorial: “and their mind completely turns around and they realize their country’s greatness and how proud they are to live there.” Is Warhol’s statement a bit tongue-in-cheek? Also, is Faustine’s art commenting on who is left out of this response?

Diaz: I think Warhol was proud to be an American, and I know Faustine is as well. Both had ancestors that come to the USA from elsewhere. Warhol was a bit of a chameleon when it came to taking sides on issues, but both artists depict sites that are very much a part of our collective conscience. The past is often mythologized and institutionalized, so we grow up thinking a certain way about Christopher Columbus or the Statue of Liberty, but it often erases additional histories from other cultures. Faustine unearths the unseen by creating her visual barriers, in red and black lines, that can symbolize these lost narratives and separates the site and spectator.

Johnson: Chloe Wise’s deconstruction of advertising, the field in which Warhol worked, seems explicitly Warhol-esque.

Diaz: Absolutely. Wise is well aware of the seduction behind advertising. Warhol was a commercial illustrator in the 1950s making drawings for ads selling shoes, cars, jewelry, etc. He had to make it appealing, then he took what he learned and utilized it in his Pop productions in the 1960s and beyond.

Johnson: In America, Warhol writes about how cable and satellite dishes have taken the mystery out of the rest of the world. Warhol died two years later, never really experiencing the internet. What do you think Warhol would have made of Instagram, TikTok?

Diaz: He would certainly be involved in many ways!

March 2021

José Carlos Diaz is chief curator at The Warhol in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.