Omar: An Opera of the Past and Present

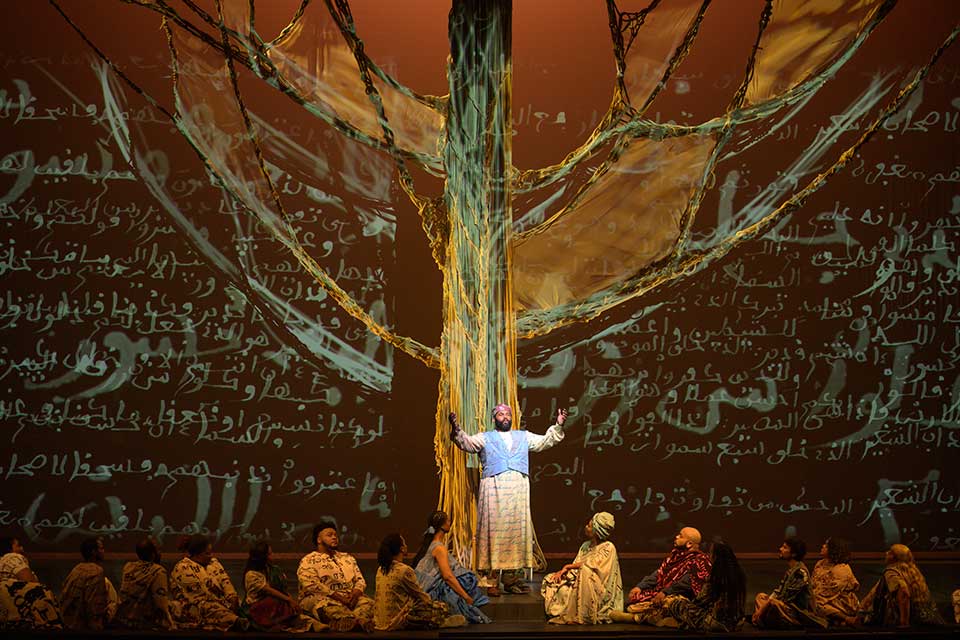

The opera Omar, which had its North Carolina premiere at Carolina Performing Arts on February 23, 2023, is an intense journey into the life of its eponymous character. With the lead performed by Jamez McCorkle, Omar demonstrates Omar Ibn Said’s unwavering faith in Allah, the duress of enslavement, and the powers of writing.

Created by Grammy Award winner Rhiannon Giddens, and co-composed with Michael Abels, who is behind such films as Get Out, Omar is based on the autobiography of Omar Ibn Said (also known as Uncle Moreau or Prince Omaroh), the only known slave narrative written in Arabic. Ibn Said was an enslaved African scholar who was captured in Fouta Toro in the delta of the Senegal River in 1807 at the age of thirty-seven and brought to Charleston, South Carolina. Prior to his capture, Omar had spent most of his life studying under prominent African scholars and was highly educated in theology, astronomy, mathematics, and more. Omar escaped his master and was later imprisoned in Fayetteville, North Carolina, where he was bought by James Owens, who also happened to be the brother of North Carolina governor John Owens. Omar described Owens as being kinder toward him. Impressed by his writing and strong faith in Islam, Owens offered Omar an Arabic translation of the Bible.

The opera mixes West African styles of storytelling with opera techniques and offers a compelling story that, until now, was unknown to many—including Giddens, who is a North Carolina native. The opera weaves in flashbacks of Omar’s happy life in his native Fouta Toro and the atrocities of enslavement as Omar is uprooted from his aristocratic life to the Americas where he must endure bondage and subjugation.

The opera offers a more complex portrayal of slave owners with one constant: they might have differed in their treatment of the enslaved, but they all believed in the supremacy of the white race. Even though Owens recognized Omar’s erudition, he never freed him from slavery. The continuities between Omar Ibn Said’s life and the contemporary experiences of African Americans are clear at the beginning and end of the opera.

The singing crawls under your skin and soothes you even as it sometimes conveys the pain and despair of the enslaved.

Omar is also a musical masterpiece. It is no surprise that it recently earned Giddens the 2023 Pulitzer Prize for music. Jamez McCorkle’s tenor is just divine in his company debut. The music is an eclectic medley of genres ranging from Senegalese music, blues, jazz, Arabic dirges, to negro spirituals. The singing crawls under your skin and soothes you even as it sometimes conveys the pain and despair of the enslaved. It stays with you for days.

The mesmerizing set skillfully renders the architecture of Fouta Toro at the time of Omar’s capture as well as the fields of Charleston. Ropes, drapes, and Arabic writing physically and metaphorically entwine to offer a visual spectacle and set the general mood of the opera. The Arabic script is everywhere, including on the costumes, highlighting Omar’s skills as a master scribe. Ah, the costumes! The mixing of fabrics, soft colors, and bubbly shapes give the enslaved so much grace and dignity in their bondage.

If I could find any flaws in this performance, it is that the transcription projected at the top of the stage made it hard to watch and read at the same time. But this could have been the configuration of Memorial Hall itself. If this show comes to your town, you must go see it. I feel blessed to have seen it during Black History Month and in Chapel Hill, less than a hundred miles from Fayetteville, where Omar lived and is buried.

Omar Ibn Said lived to be ninety-three and authored fourteen manuscripts, including his autobiography. There is a belief that Omar converted to Christianity, which many scholars have refuted because his Bible and autobiography show that he still invoked Allah until his death. A mosque in Fayetteville is named after him. An upcoming book entitled I Cannot Write My Life: Islam, Arabic, and Slavery in Omar Ibn Said’s America, co-written by Mbaye Lo (Duke University) and Carl Ernst (UNC Chapel Hill), focuses on Omar Ibn Said’s surviving eighteen manuscripts to offer a more comprehensive account of Omar’s life and contributions.

Greenville, North Carolina